KOLUMN Magazine

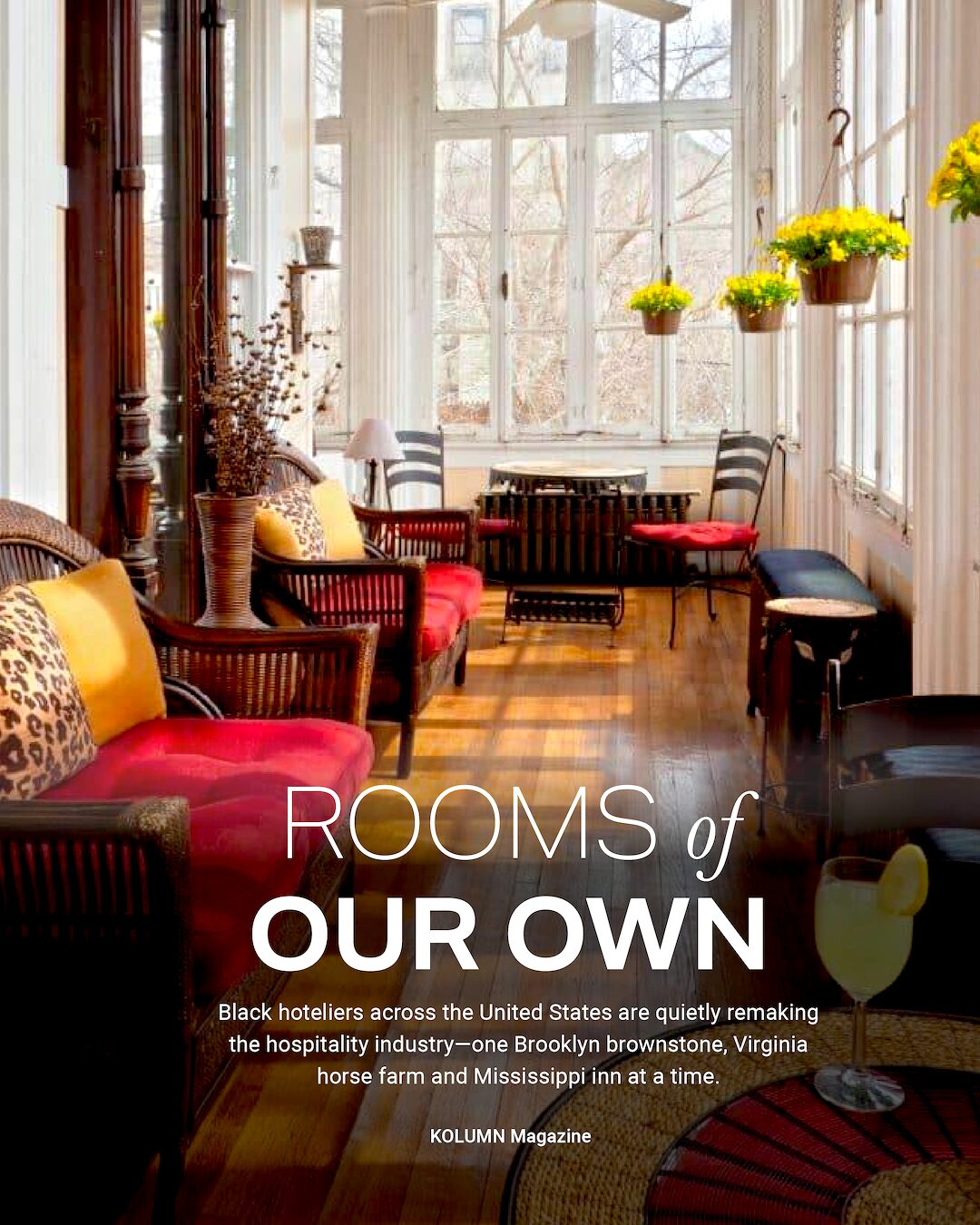

Rooms of Our Own

Black hoteliers across the United States are quietly remaking the hospitality industry—one Brooklyn brownstone, Virginia horse farm and Mississippi inn at a time.

By KOLUMN Magazine

On a quiet block in Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood, the Akwaaba Mansion doesn’t glow so much as it exudes warmth—lamplight spilling from tall parlor windows, the soft clink of dishes from the kitchen, the low murmur of guests lingering over breakfast. It is, in some ways, an ordinary morning at a four-room bed-and-breakfast. And yet nothing about this place is ordinary.

Akwaaba is part of a small but growing constellation of Black-owned hotels, inns, and bed-and-breakfasts across the United States—a network that stretches from a horse country resort in Virginia to a restored Victorian in Mississippi’s capital city. These properties offer more than a place to sleep; they are repositories of memory and ambition, shaped by owners who have had to push past banks, biases, and a hospitality industry in which Black people are overrepresented in service jobs and dramatically underrepresented at the ownership table.

This is a story about lodgings, but also about capital—who gets it, who doesn’t, and what Black hoteliers build anyway.

A Legacy Born of Exclusion

Long before “boutique hotel” became a marketing tagline, Black travelers relied on word of mouth and, later, on Victor Hugo Green’s Negro Motorist Green Book to find places that would take them in. These guides listed hotels, tourist homes, and resorts where Black motorists could safely sleep, eat and refuel in a country where “sundown towns” and whites-only signs made routine business travel potentially lethal.

Some of those lodgings grew into full-fledged Black leisure enclaves: Idlewild in Michigan, sometimes called the “Black Eden,” where professionals, artists and musicians vacationed; and a loose “Chitlin’ Circuit” of hotels, motels and nightclubs that hosted touring Black entertainers and traveling salespeople.

But as segregation laws fell and interstate highways carved around many Black neighborhoods, a cruel irony took hold. Freed to stay anywhere, Black travelers often left for newer chain hotels on the bypass, while the Black-owned properties that had sustained them were bulldozed by urban renewal or starved of investment. By some estimates, fewer than 20 percent of Green Book–listed sites still stand.

What survives today is a patchwork—some grand, some modest, many fragile—maintained by owners who see themselves as stewards of history and as entrepreneurs trying to make the numbers work in a capital-intensive business.

The Capital Problem

Hotel ownership anywhere is expensive. For Black Americans, the financial calculus has an extra, familiar layer: discrimination.

Federal Reserve small-business surveys have consistently found that firms owned by people of color are less likely to be approved for credit, more likely to be discouraged from even applying, and more likely to receive smaller loans at higher interest rates when they do get financing.

Recent data from Goldman Sachs’s 10,000 Small Businesses Voices initiative found that Black small-business owners are less likely than their white peers to secure bank loans and more likely to report facing predatory terms. Other studies put the denial rate for Black-owned firms far above that of white-owned businesses, even when controlling for creditworthiness.

For would-be hoteliers, that translates into years of saving, piecing together friends-and-family capital, leveraging home equity, or taking on side jobs just to get an initial down payment. A CBRE report on Black and Latino hotel ownership notes that despite a “rich history of minority hotel ownership,” barriers like access to capital and limited industry networks continue to keep ownership levels disproportionately low.

Many Black innkeepers and hotel owners are, quite literally, bank customers whose relationship with lenders has been defined not by concierge upgrades but by rejection letters, opaque underwriting standards, and the quiet sting of being told, in so many words, that their dreams are too risky.

And yet they persist.

Akwaaba: A Bed-Stuy Brownstone, An Empire of Welcome

If there is a spiritual headquarters for the contemporary Black B&B movement, it may well be Akwaaba Mansion, the 1860s Italianate home that anchors a leafy block of MacDonough Street in Brooklyn. The word akwaaba means “welcome” in Twi, and welcome is exactly what former magazine editor Monique Greenwood set out to create when she and her husband, Glenn Pogue, opened their first inn here in the mid-1990s.

Greenwood had spent years ascending the ranks of glossy lifestyle media, ultimately becoming editor in chief of Essence magazine. In 2001, she did something that still startles her readers: she quit one of the most coveted jobs in Black media to run a bed-and-breakfast full time. “I wanted to build something we controlled,” she has explained in interviews, describing her decision to pivot from publishing to hospitality.

By then, she and Pogue had already mortgaged their home to buy the Brooklyn mansion. As she tells it, traditional lenders were skeptical that a Black couple could make an upscale inn work in a neighborhood that, at the time, many outsiders still associated more with crime statistics than weekend getaways.

Two decades later, Akwaaba has grown into a small collection of inns: the original Brooklyn property; guesthouses in Washington, D.C., and Cape May, New Jersey; a mansion-turned-resort in Pennsylvania’s Pocono Mountains; and a B&B in Philadelphia. The couple’s work even spawned a reality series, “Checked Inn,” which followed Greenwood—who jokingly calls herself the company’s “Chief Enjoyment Officer”—as she managed staff, soothed anxious brides, and fussed over menus.

Akwaaba’s spaces lean heavily into Black cultural memory. Rooms may be themed around beloved authors or jazz legends; breakfast conversations range from gentrification to HBCU homecomings. Guests describe an atmosphere that feels like the best parts of visiting a beloved aunt: exacting standards tucked inside easy laughter.

Yet for all the romance of this narrative—the leap of faith, the lovingly restored house—the business remains work. B&Bs are labor-intensive, and margins are thin. Greenwood has spoken candidly about how crucial it was to diversify revenue, hosting weddings and corporate retreats, and about the constant need to reinvest profits back into properties that banks were once reluctant to back in the first place.

Magnolia House Inn: A Wedding Chapel in Hampton

Nearly 350 miles south, in Hampton, Virginia, Joyce and Lankford Blair run another Victorian-era inn that stands as both a refuge and a statement.

Magnolia House Inn sits on a quiet downtown street, its 1885 Queen Anne façade framed by magnolia trees and a wrought-iron fence. The three-room B&B has a small on-site wedding chapel, the kind of intimate space where couples say their vows beneath stained glass and chandeliers.

The Blairs opened the inn in 2004 and welcomed their first guests two years later. They were drawn, in part, by a sense of absence: in their travels, they rarely saw Black faces behind the check-in desk—let alone on the deed. They wanted, as Joyce Blair has put it, to create a place where guests could feel “intentionally seen,” whether they were business travelers, military families from nearby Langley Air Force Base, or couples eloping on a budget.

The house had been a family residence, then modest apartments for airmen and their partners. Restoring it meant wrestling with permits, inspections, and the inevitable surprise costs hidden in any 19th-century structure. Financing, again, was a patchwork: savings, small business loans, and what Joyce calls “a lot of faith.”

Guests who write about Magnolia House tend to dwell less on its status as a Black-owned business than on its service: the “restaurant-quality” breakfasts, the attention to detail, the feeling that the innkeepers remember not only your name but your story. One writer described it as “not a superior Black-owned B&B, but a superior B&B—full stop.”

For the Blairs, that distinction matters. Visibility is important; excellence is non-negotiable.

A Billionaire in the Barn: Salamander’s New Kind of Luxury

If Akwaaba and Magnolia House represent the intimate end of Black-owned hospitality, Sheila Johnson’s Salamander Collection exists at the opposite pole: large-scale, luxury resorts where spa menus run to multiple pages and the wine list needs its own index.

Johnson, best known as the co-founder of Black Entertainment Television, sold her stake in BET in 2001. Four years later, she launched Salamander Hotels & Resorts, investing a portion of her media windfall into hospitality and real estate. Today, she is CEO of a portfolio that includes Innisbrook Resort in Florida, Hotel Bennett in Charleston, Half Moon in Jamaica, and Aurora Anguilla, along with Salamander Resort & Spa in Middleburg, Virginia.

Salamander Middleburg, set on 340 acres in the Blue Ridge foothills, is the brand’s flagship. Drive up its long entry road and you pass manicured paddocks, a riding ring, and barns that nod to the region’s equestrian heritage; inside, the décor feels more like a stately country house than a traditional hotel lobby.

Johnson has described Salamander as her “third act,” after careers in music and media. In interviews, she’s also been frank about how personal setbacks—a painful divorce, skepticism from lenders and local officials—shaped her determination to build something on her own terms.

At Salamander, that determination shows up not only in design but in programming. Each August, the resort hosts The Family Reunion, a multiday food and wine festival celebrating Black culinary talent, co-created with chef Kwame Onwuachi. The weekend brings together chefs like Carla Hall and Gregory Gourdet, Virginia Ali of Ben’s Chili Bowl, and wine professionals from across the diaspora, transforming a traditionally white, old-money setting into a joyous, intergenerational gathering.

In an industry where Black workers are more likely to be cleaning rooms than signing franchising agreements, Johnson’s presence as an owner—one of the few Black women to helm a major luxury collection—signals to younger hoteliers what might be possible.

The Orchid in Jackson: History at the Doorstep

The Orchid Bed & Breakfast in Jackson, Mississippi, looks almost unassuming from the street: a handsome but modest property set within walking distance of downtown. Step inside, and you find a different story—a lovingly refurbished Black-owned inn that sits within blocks of sites central to the state’s civil rights history.

The Orchid markets itself as “the premier, Black-owned bed and breakfast in Mississippi,” and its location does a lot of the talking. Guests can stroll to the Mississippi Civil Rights Museum, the Smith Robertson Museum and Cultural Center, the International Museum of Muslim Cultures, and the Eudora Welty House and Garden.

Staying here is less about a resort bubble than about immersion: breakfast, then a morning at the civil rights exhibits; an afternoon walking past the old bus depot where activists were once arrested; an evening on the porch, digesting not just food but history. The inn becomes a bridge between past and present, hospitality and hard truth.

Islands and Gardens: A Wider Map of Black-Owned Stays

Zoom out, and the map of Black-owned hotels and B&Bs in the U.S. becomes more intricate.

On Martha’s Vineyard, The Oak Bluffs Inn, a ten-room property in the heart of Oak Bluffs, is part of a long tradition of Black vacationing on the island. Once a modest boarding house, the inn today offers individually decorated rooms and a porch that functions as a front-row seat to summer’s parade of beachgoers and ice-cream seekers. It was even featured in the 1994 film The Inkwell, a cult classic of Black summer cinema.

In Spartanburg, South Carolina, Clevedale Historic Inn and Gardens occupies a former country estate, its English-style gardens now host to weddings, concerts and community events. Owners Pontheolla and Paul Brown have transformed the property into a hybrid: part traditional B&B, part cultural venue.

Across the country, directories like Black Hotel Guide and Stay Black Experience have begun cataloging these properties—listing Black-owned hotels, resorts, B&Bs and short-term rentals in cities from Detroit to New Orleans. Major travel outlets, including Condé Nast Traveler and The Points Guy, now publish regular roundups of Black-owned hotels in the U.S. and abroad, a visibility that would have been unthinkable a generation ago.

The listings are uneven, and the economics are fragile. But together they form something like a new-era Green Book—less about avoiding danger, more about seeking out joy, culture and solidarity.

Why Ownership Matters

It would be tempting to reduce the importance of Black-owned hotels and B&Bs to a matter of representation—to say that seeing a Black woman at the head of a luxury resort, or a Black couple running a Victorian inn, simply “inspires the next generation.”

It does that. But it also changes who benefits from the tourism economy; who decides which stories are told in lobby art and curated bookshelves; whose grandmother’s recipes make it onto brunch menus.

For guests, especially Black guests, staying at these properties can feel like a kind of quiet homecoming. The décor may include portraits of Black writers and musicians, or archival photos of the local Black community. Staff might steer you toward a nearby soul food spot that never makes it into glossy city guides, or to a church picnic doubling as a voter-registration drive. The result is a travel experience where Black life is centered rather than incidental.

For owners, the work is less romantic. It is negotiating with contractors who assume you can’t afford market rates; fielding questions from lenders who want more collateral than you can reasonably provide; keeping occupancy up through pandemics and recessions. Surveys from the Federal Reserve and other institutions suggest that Black business owners often hesitate to apply for loans at all, expecting denial—a learned response rooted in decades of unequal treatment.

Even successful hoteliers talk about “making the math work” year to year. They are bank customers in the most literal sense—depositing daily receipts, pleading for line-of-credit extensions, watching interest rates climb—and their balance sheets are influenced by decisions made in boardrooms far from their front desks.

And yet, when guests arrive, what they encounter is not that struggle but the distilled product of it: a perfectly made bed, a coffee mug set down just when the conversation calls for a pause, a sense that, at least for a night or two, you are in a place that was designed with you in mind.

The Next Chapter

The renewed interest in Black-owned hotels and B&Bs—reflected in travel-media features, social-media directories, and awards like Travel Noire’s recognition of Salamander Middleburg as a standout Black-owned resort—suggests a slowly shifting landscape.

But visibility alone will not fix entrenched capital gaps. Policy experts argue for reforms ranging from stronger enforcement of fair-lending laws to more flexible underwriting that accounts for historic discrimination, as well as targeted public and private investment in Black-owned businesses.

For now, much of the work happens one reservation at a time. Travelers choose where to spend their money; banks decide whom to back; local tourism boards decide which properties make the brochure. The future of Black-owned hospitality will be shaped in those choices as much as in federal policy or corporate boardrooms.

Back in Brooklyn, as breakfast winds down at Akwaaba, guests drift out to explore the city. The owners turn to the less glamorous work of innkeeping: laundry, emails, another round of calls with vendors. Their story, like those of so many Black hoteliers, is not just about survival in a hostile market. It is about the insistence that Black travelers—and, indeed, all travelers—deserve places where welcome is not an afterthought but the organizing principle.