KOLUMN Magazine

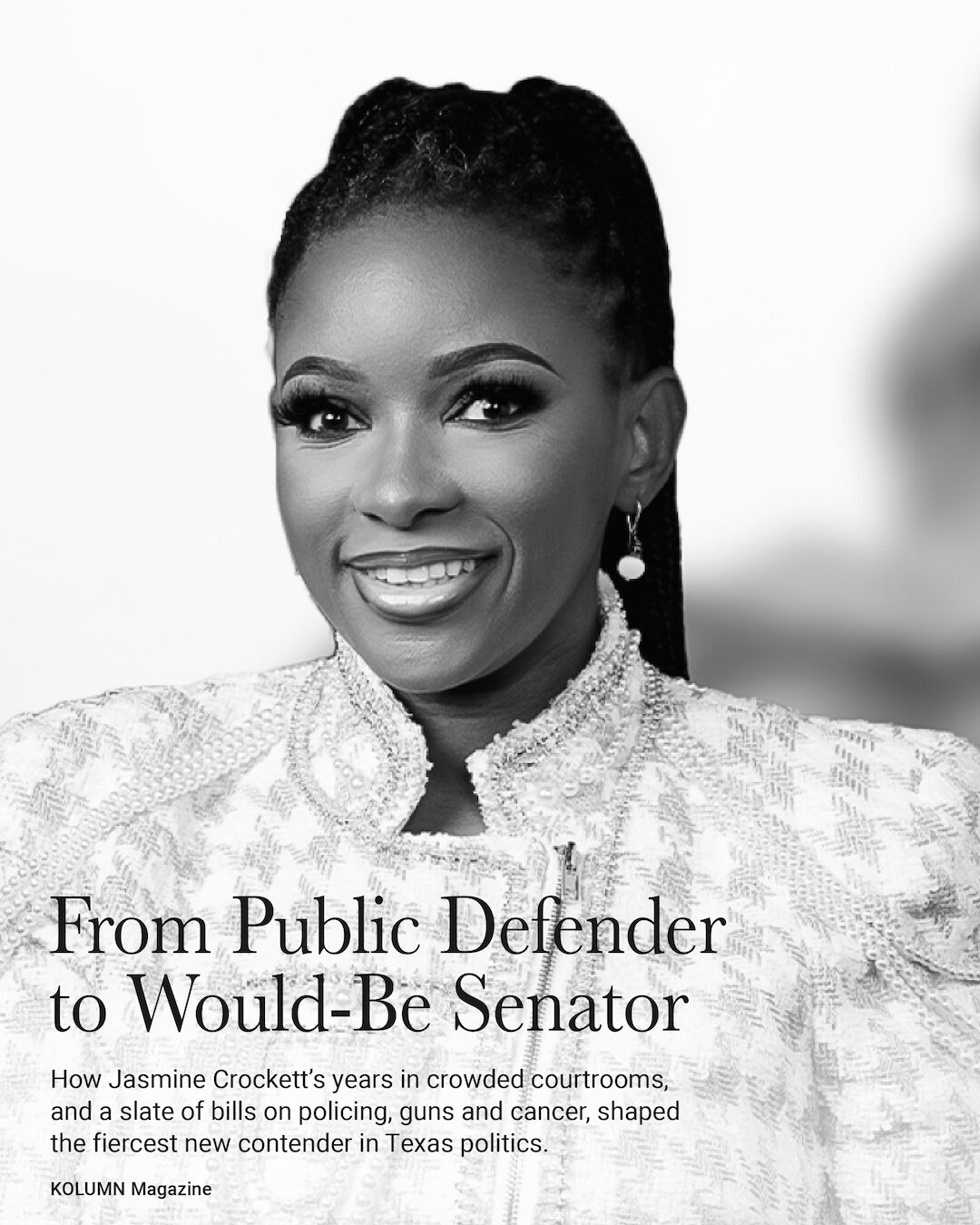

From Public Defender to Would-Be Senator

How Jasmine Crockett’s years in crowded courtrooms, and a slate of bills on policing, guns and cancer, shaped the fiercest new contender in Texas politics.

By KOLUMN Magazine

Jasmine Crockett’s bid for the U.S. Senate began, characteristically, with a dare.

After months of public deliberation over whether she could “actually win a general, not just a primary,” the 44-year-old congresswoman from Dallas stepped into a race that Democrats consider both long-shot and existential: unseating Republican Sen. John Cornyn in Texas and, in the process, helping to redraw the balance of power in Washington.

Her announcement came just before the filing deadline, a last-minute jolt that followed former Rep. Colin Allred’s decision to abandon his own Senate run and seek a newly drawn House seat instead. It instantly reshaped the Democratic primary, pitting Crockett against state Rep. James Talarico, an Austin progressive whose own viral committee moments have made him a liberal favorite.

A victory would align with the momentum of gains earned by other Black women earlier this year, joining the ranks of mayors-elect Dorcey Applyrs of Albany, New York; Mary Sheffield of Detroit; Christal Watson of Kansas City, Kansas; Joi Washington of Media, Pennsylvania and Sharon Owens of Syracuse, New York.

Crockett enters as something different: a civil-rights attorney turned politician whose career has been defined as much by legislation as by the sharp, meme-ready exchanges that have made her “the bad girl of C-SPAN,” a label cemented by a recent Saturday Night Live impression and a knack for turning Republican attacks into fund-raising slogans.

Beyond the theatre of politics is a more methodical story: a woman whose encounters with racism as a college student pushed her into law school; whose years as a public defender in rural Texas brought her face to face with the machinery of mass incarceration; and whose legislative portfolio in Congress—on policing, guns, cancer screening, and civil rights—offers a preview of the agenda she would take statewide.

Now she is betting that this story, and the bills that grew out of it, can help her do something no Democrat has done since 1994: win a statewide race in Texas.

From Rhodes to the courtroom

Crockett’s path to the Senate began far from Dallas, in St. Louis, where she was born to a minister father and a mother who worked in health care.

At Rhodes College in Memphis, she initially planned to become an accountant. Then came the hate mail.

As Crockett has recounted in interviews, racist letters and vandalism targeting Black students—including keyed cars and anonymous threats—left her campus reeling. The administration brought in lawyers from the Cochran Firm, the civil-rights practice once led by Johnnie Cochran, to advise students. Watching a Black woman attorney advocate for them in real time, Crockett has said, changed her sense of what a career could be.

She left Rhodes with a degree in business administration but a new direction: law.

Crockett enrolled at Texas Southern University’s Thurgood Marshall School of Law before transferring to the University of Houston Law Center, where she earned her J.D. in 2006. Years later, when she took the oath of office as the representative for Texas’s 30th Congressional District, she became the first Black graduate of the UH Law Center to serve in the U.S. House.

Her first years out of law school were spent as a public defender in Bowie County, a largely rural swath of northeast Texas. There, she handled juvenile and adult cases—often representing poor defendants of color wrestling with the full weight of the criminal justice system.

Later, she opened her own firm in Dallas, focusing on criminal defense and personal-injury work while taking pro bono cases for Black Lives Matter activists arrested during protests against police brutality. The work, she has often said, trained her to think in terms of systems, not just single clients: police, prosecutors, health insurance companies, landlords, all interlocking.

Those years in the courtroom would become the backbone of her political pitch: that she understands, intimately, what happens to people on the losing end of policy decisions made in rooms they will never see.

A reluctant politician in the Texas House

By her own telling, Crockett did not grow up dreaming of holding office. When she ran for the Texas House in 2020—challenging an incumbent Democrat who had won a special election just months earlier—it was less out of personal ambition than exasperation with the laws she saw being written in Austin.

She narrowly won that Democratic primary runoff and cruised to victory in the general election, becoming, in the 2021 session, the only Black freshman and the youngest Black lawmaker in the Texas Legislature.

The timing was brutal. Republican leaders were pushing a wave of conservative priorities—from abortion restrictions to new voting rules—through what some advocates called the most right-leaning legislative session in modern state history.

As a member of the Criminal Jurisprudence Committee, Crockett filed more bills than any other freshman, according to her office, focusing on criminal-justice reforms and police accountability. She helped found both the Texas Progressive Caucus and the Texas Caucus on Climate, Energy, and the Environment, alliances that gave her a platform far beyond her freshman rank.

Her defining moment in Austin came in the summer of 2021, when she joined fellow Democrats in leaving the state to deny Republicans a quorum on a sweeping voting bill that, among other provisions, tightened rules around mail-in ballots and limited local efforts to expand access to the polls. The move ultimately failed to block the legislation, but it made Crockett a familiar face in national coverage of the voting-rights fight.

That visibility set the stage for her next leap.

Going national

When longtime Dallas Rep. Eddie Bernice Johnson announced in late 2021 that she would retire after nearly three decades in Congress, she made her preference explicit: she wanted a woman to succeed her. Within days, she endorsed Crockett, then still in her first term in the state House, praising her “high energy,” “shrewd intelligence,” and “incessant drive.”

Crockett won the crowded Democratic primary and, in January 2023, was sworn in as the U.S. representative from Texas’s 30th District, a majority-minority seat based in southern Dallas.

In Washington, she joined the Congressional Progressive Caucus, though she has bristled at the label “progressive,” insisting that her positions—on voting rights, reproductive health, and gun safety—are “common sense.”

Her committee assignments, including a seat on the Judiciary Committee’s Oversight Subcommittee, put her directly in the crosshairs of the partisan battles of the Biden and Harris administrations.

It didn’t take long for her to become a viral figure. When Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene mocked her eyelashes during a contentious House Oversight hearing, Crockett fired back with a taunt about Greene’s “bleach-blonde, bad-built body”—a moment that ricocheted across social media, inspired a line of fund-raising merchandise dubbed the “Crockett Clapback Collection,” and eventually spawned the SNL impersonation.

Her critics—conservative commentators, some Republican colleagues—have called her style uncivil, even “performative.” Supporters, especially younger voters and Black women, describe it as something closer to emotional honesty in a political arena that often rewards decorum over plain speech.

But the viral clips obscure a quieter, more technical side of her work: a legislative record centered on public safety, health equity, and civil rights.

The bills behind the brand

Crockett is not, by the numbers, among the House’s most prolific authors of stand-alone bills. Many of the major measures associated with her name are ones she has helped lead or amplify as a co-sponsor, rather than primary sponsor—a common reality for relatively junior members in a chamber where seniority still matters. What stands out is the coherence of the themes.

Policing and civil rights

In 2024, Crockett signed onto the latest iteration of the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act, a sweeping package that would, among other provisions, restrict qualified immunity for law-enforcement officers, create a national police misconduct registry, and set new standards for use-of-force policies.

She also co-sponsored the federal CROWN Act of 2024, legislation that would bar discrimination based on hair texture or protective hairstyles—an issue that resonates deeply with Black professionals who have faced workplace penalties for braids, locs, and Afros.

For Crockett, who has built a brand around refusing to tone down her own presentation to fit Capitol Hill norms, the symbolism is straightforward: “representation” is not just about who gets a vote in a committee markup, but who gets to show up fully as themselves in the first place.

Health equity and prevention

Less visible, but arguably just as consequential, is her work on health-equity legislation. Crockett is a co-sponsor of the SCREENS for Cancer Act of 2024, which aims to expand access to cancer screening and navigation programs in underserved communities—an attempt to address racial and geographic gaps in early detection.

The bill, which has drawn bipartisan support and was placed on the House Union Calendar in mid-2024, would reauthorize and modernize federal cancer-screening programs, with a specific focus on reaching communities that lack easy access to specialists or up-to-date diagnostic equipment.

Crockett has also backed a bipartisan resolution designating “Disability Reproductive Equity Day,” aligning herself with efforts to highlight the barriers people with disabilities face in accessing reproductive and sexual healthcare.

In a Congress where many debates over reproductive rights have focused narrowly on abortion bans and court decisions, these measures sketch a broader vision: one in which health care is not only legal but materially reachable for people who have long been on the margins of the system.

Guns, culture, and the politics of symbolism

On gun policy, Crockett is a co-sponsor of the Gun Theft Prevention Act, which would require federally licensed firearms dealers to adopt more stringent security measures—reinforced safes, alarm systems, surveillance cameras—to reduce thefts that funnel weapons into the illegal market.

In a state where support for gun rights is often treated as a litmus test for statewide viability, that vote could become a line of attack in the general election. Crockett’s bet is that there is a critical mass of Texans—suburban parents, law-enforcement officials, young voters shaped by mass-shooting drills—who see tightened security at gun shops as common sense rather than confiscation.

Her legislative portfolio also contains measures that are partly symbolic but culturally resonant. Among them: a House resolution expressing support for the designation of June 2025 as Black Music Month, a nod to the economic and artistic contributions of Black musicians; and her backing of commemorative efforts around disability justice and reproductive equity.

None of these bills, taken individually, would remake Texas. But together, they amount to a kind of through-line: a focus on how systems treat people who are easiest to ignore—poor defendants, Black workers, disabled patients, the families left behind when guns are stolen and used in crimes.

The risks—and rewards—of running

Crockett’s Senate bid is unfolding against an unforgiving electoral map. Republicans currently hold the Senate and, thanks to a Supreme Court-blessed redistricting map, have reinforced their structural advantage in Texas. Democrats need to flip at least four seats to reclaim the majority; Texas is both tantalizing and punishing—expensive to campaign in, stubbornly red at the statewide level, but steadily trending more competitive in its metro cores.

Her primary opponent, James Talarico, has his own national profile, buoyed by viral speeches against school vouchers and religious mandates in public classrooms. Allred’s exit from the race, and his decision to seek a safer House seat, reflects just how high the stakes are; Democrats fear a bloody primary will weaken whoever emerges to face Cornyn—or, if he loses his primary, a Republican like Attorney General Ken Paxton or Rep. Wesley Hunt.

Crockett, for her part, argues that she offers something Democrats have often lacked in Texas: a candidate who can electrify the party’s base—Black voters in Dallas and Houston, young progressives, union households—while still making an economic pitch to independents disillusioned with Republican governance.

Her educational story—Rhodes College, then the University of Houston Law Center; first Black UH Law alum to reach Congress—has become a centerpiece of her biography, allowing her to speak fluently about student debt, college access, and the fragility of campus safety for students of color.

Her personal style is both a lightning rod and a calling card. She is acutely aware that she is walking in a lineage that runs from Shirley Chisholm to Barbara Jordan to Maxine Waters: Black women who have refused to shrink themselves to fit the expectations of institutions built without them in mind.

The question is whether that persona, and the legislative record underneath it, can travel beyond the confines of TX-30.

A test of what Texas—and the country—wants now

Crockett likes to say that she did not choose politics so much as politics chose her: the racist notes at college, the young clients facing decades in prison, the voting-rights bills she watched move through the Texas House.

Her Senate campaign transforms those episodes into a statewide argument. She is not running on bipartisanship in the traditional sense; her brand is confrontation, not conciliation. At rallies, she talks openly about “coming for” Donald Trump and calls out what she describes as racism within the Republican Party.

But embedded in her candidacy is a more nuanced question for Texas and for Democrats nationally: In an era of viral politics, is there room for a candidate whose most-watched moments are Clapbacks On Tape but whose docket, back in the Capitol, is full of dense, incremental bills about cancer screening schedules and the security specs of gun safes?

If Crockett can make that case—to voters in Houston’s union halls, in Dallas’s Black-owned coffee shops, in the small towns where she once worked as a public defender—her Senate run will be more than a dare. It will be a test of whether the skills honed in courtrooms and committee rooms can still move an electorate saturated with outrage and spectacle.

And if she can’t, she will likely return to the House with even more name recognition, a deepened donor network, and an even stronger claim to being one of the defining voices of her party’s future—whether or not Texas is ready to send her to the upper chamber.