The

Cemetery

Was Never

Empty

A lawyer in Tampa, a historian in Portsmouth and a forensic anthropologist in Montana are part of a national effort to reclaim Black burial grounds the nation tried to forget.

By KOLUMN Magazine

On a warm February afternoon in Tampa, a woman in a white dress walked slowly across a patchwork of cracked asphalt and scrub grass, reading a eulogy to a grave no one could see.

“You may trod me in the very dirt,” Jeraldine Williams intoned, borrowing from Maya Angelou as she traced the outline of a burial that only ground-penetrating radar had found, “but like dust, I’ll rise.”

Under her feet lay what remained of Zion Cemetery, Tampa’s first Black burial ground, established in 1901 and long ago covered by warehouses, homes and a public housing complex. City records and newspaper clippings suggested that more than 380 people were buried there; radar surveys confirmed hundreds of grave shafts still beneath the surface.

One of those graves belongs to Williams’s great-great-grandmother, Anna Rebecca Wyche — a cook, a mother of eleven, buried here in 1912 when Zion was the place where Black Tampa said goodbye to its dead. For a century, Wyche’s grave was treated as real estate. Only in the last few years has it been reclaimed as hallowed ground.

“I knew about it, I heard about it, I read about it,” Williams said later. “I thought: so here’s another injustice that has occurred.”

Her family’s story is part of a larger reckoning underway across the United States, where bulldozers, survey crews and reporters have kept colliding with the buried infrastructure of racial segregation: Black cemeteries and burial grounds paved over, sold off, or simply forgotten.

Over the last two decades, across cul-de-sacs and college campuses, under high schools and parking lots, the bones of African Americans have resurfaced, forcing cities and institutions to confront how thoroughly Black death — like Black life — was pushed to the margins.

These rediscoveries have a familiar rhythm. A construction project pauses when a backhoe lifts a skull from the clay. An archivist or curious reporter compares old plat maps with modern parcels, realizing an all-Black cemetery lies beneath a warehouse or football field. Descendants, often women, show up at planning meetings with armfuls of death certificates and family Bibles.

What distinguishes this moment is not that these graves are being found — they were always there — but that, for once, the people buried in them are starting to be treated as ancestors rather than obstacles.

A century of erasure

To walk the country through these sites is to move through an atlas of displacement.

In lower Manhattan, the rediscovery of a colonial-era African Burial Ground in 1991 revealed that as many as 15,000 Africans — some free, most enslaved — had been interred just north of the early city, their graves later entombed under up to 25 feet of landfill and government buildings.

In Richmond, Virginia, the Shockoe Hill African Burying Ground — once labeled “Grave Yard for Free People of Colour and Slaves” on 19th-century maps — held an estimated 22,000 people of African descent before being gradually sliced apart by roads, rail lines and public works.

In Portsmouth, New Hampshire, human bones began surfacing in 2003 when city workers tried to repair a sewer line beneath Chestnut Street. Archaeologists eventually determined that this stretch of asphalt sat atop an 18th-century burying ground that once held nearly 200 free and enslaved Africans — the only archeologically verified African cemetery of its era in New England.

Still, it is the burst of discoveries since the mid-2000s, propelled by urban redevelopment and a new generation of Black preservationists and journalists, that has turned once-isolated fights into a national conversation.

Archaeologists and advocates now speak of a “landscape of absence”: Black burial grounds built on marginal land — low-lying, flood-prone, adjacent to railroad tracks or industrial zones — that later became prime targets for highways, public housing and speculative development. A 2022 Senate report on the African American Burial Grounds Preservation Act notes that many Black cemeteries “are in a state of disarray or are inaccessible,” the result of segregationist laws and discriminatory planning decisions that made Black deaths easier to ignore.

That federal law, enacted as part of the 2023 budget and now codified in the U.S. Code, created a national program within the National Park Service to help identify and preserve African American burial sites. Yet funding has been slow to arrive, and the burden of remembrance still falls largely on local volunteers, descendant families and a small cadre of scholars.

Across this emerging map, a few places encapsulate both the violence of forgetting and the fragile work of repair.

Zion Cemetery: The vanished city of the dead

For decades, the story of Tampa’s Zion Cemetery circulated as rumor and family lore. The city’s first all-Black cemetery, opened in 1901 on a ridge north of downtown, appeared on early-20th-century maps and in newspaper obituaries. But by the late 1920s, as white developers eyed the land, the graves were already under threat.

In the 1950s and ’60s, public housing and warehouses rose over the site. Residents of the Robles Park Village apartments told their children not to play too far out back, where the ground sank in odd depressions. Some elders recalled watching earth-moving equipment churning through what they’d been told was a cemetery.

Officially, the graves had been moved. Unofficially, no one could say where.

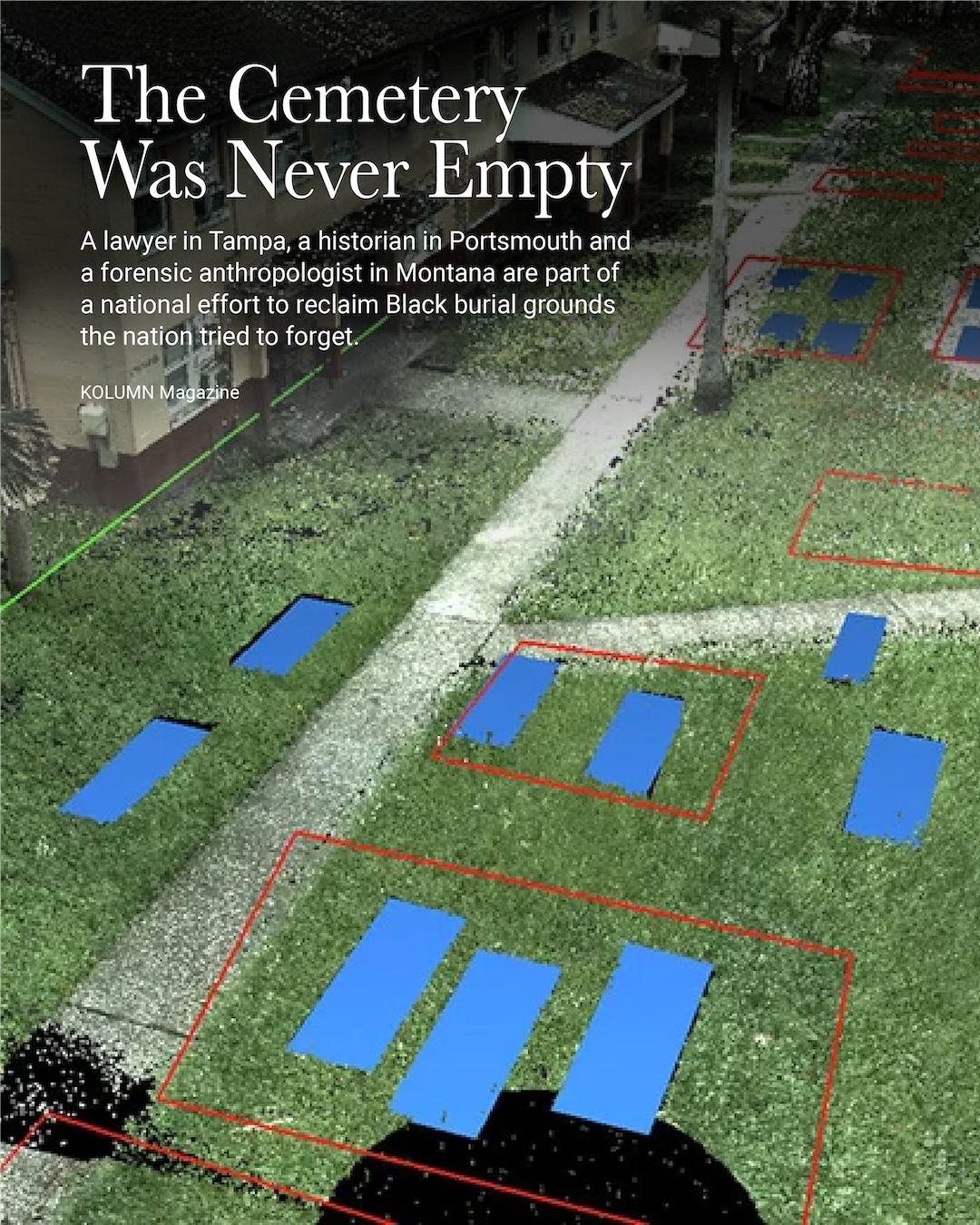

Then, in 2019, journalists at the Tampa Bay Times, acting on a tip from a local historian, overlaid historic maps with modern parcels and realized that Zion Cemetery almost certainly lay under a tangle of streets, cinderblock homes and a storage yard. Ground-penetrating radar surveys soon revealed nearly 300 grave shafts aligned in neat rows, many directly behind Robles Park Village.

Old city records gave the dead back their names: 382 individuals with recorded burials at Zion, often with occupations and addresses — laborers, laundresses, children, a preacher.

Among them was Anna Rebecca Wyche, who died in 1912. Her descendant, Jeraldine Williams, a lawyer and University of Florida Hall of Fame alumna, first went looking for Anna while tracing her family tree back toward Africa. Instead, she found a story of how American cities treat Black graves.

Williams pieced together death certificates and funeral notices until she was confident her great-great-grandmother remained at Zion. On February 17, 2022, she organized what she called a long-overdue wake. Standing in the shadow of public housing, she read a letter to Anna and recited Angelou’s words, insisting that a century of neglect could not erase kinship.

“I wanted her to know that we had found her,” Williams told an interviewer later. “That the world now knows she’s here, and that her resting place will not be ignored again.”

Zion, like many rediscovered cemeteries, is still in limbo. Robles Park Village is being demolished and redeveloped; advocates want a memorial park, a research center, and legal protections that will keep the land from being sold off yet again. A historical marker, erected in early 2025, now acknowledges the cemetery and the lives beneath the asphalt.

But for Williams, the most radical change is psychological: a city beginning to speak of Zion not as a regrettable planning error, but as sacred ground.

The men of Bullhead Camp

Where suburban Sugar Land, Texas, now advertises a quality-of-life brand — “Where Life Is Sweeter” — the ground once answered to a different name: Bullhead Bayou Camp, part of the state’s vast convict leasing system.

Here, decades after the Civil War, Black men were arrested on charges as flimsy as vagrancy and “theft of hog,” leased to private planters and corporations, and worked to death in fields and sugar mills. The 13th Amendment’s loophole — permitting involuntary servitude “as a punishment for crime” — became the legal hinge on which a new form of slavery swung.

In February 2018, construction crews building a career and technical education center for the Fort Bend Independent School District hit bone — then another bone, then an entire row of coffins. By summer’s end, archaeologists had uncovered the remains of 95 individuals in unmarked graves. Archived prison ledgers suggested they were almost all incarcerated Black men who had died while performing forced labor between 1875 and 1911.

They became known, collectively, as the Sugar Land 95.

For several years, they were numbers: Burial 1 through Burial 95. Anthropologists could say that most were young men, many showing evidence of malnutrition, manual labor and untreated injuries. But the headstones were gone; the state had stripped them of names even in death.

Then came Burial 39.

In a conference presentation last year, forensic anthropologist Meradeth Houston Snow described how the skeleton from Burial 39 told a harrowing story. The man, about 5 foot 11, bore multiple healed fractures, evidence of a gunshot wound to the hand, and a below-the-knee amputation with saw marks that suggested a crude surgical procedure — likely the cause of death.

Searching surviving death records from the nearby prison farm, researchers found a match: a 61-year-old man named Sebe Froche, originally from Georgia, who died at Bullhead Camp from “effects of leg amputation.” The record hinted that he had tried to escape. The amputation, the anthropologists inferred, may have been his punishment, or the last attempt to save his life after a guard’s bullet.

DNA testing is ongoing, but Froche is one of several Sugar Land dead for whom genealogists now have tentative identifications. The non-profit Principal Research Group and Snow’s lab use degraded bone samples and genetic-genealogy databases like GEDmatch to look for distant cousins, then painstakingly build family trees forward to the present.

Snow calls it “restoring people to their families.” It is also, in a sense, a form of historical cross-examination — confronting the official narrative of post-slavery Texas with the names and injuries of the people it buried.

The struggle over what to do with the cemetery has been almost as contested as the original discovery. Fort Bend ISD initially sought court permission to relocate the remains; descendants and activists pushed back, arguing that after a century of erasure, the men of Bullhead deserved to stay where they fell.

Ultimately, a judge ordered that the remains be reinterred on site, and the district agreed to redesign the campus around a memorial cemetery. Plans now call for a $10 million memorial park with interpretive trails linking the Sugar Land 95 cemetery to nearby historic Black sites and museums, and the Texas Historical Commission recently approved an official marker recognizing the graves as part of the state’s carceral history.

In the meantime, under a stand of young trees, a simple granite marker lists the 95 burial numbers, the years 1879–1909, and a single phrase: “We are the Sugar Land 95.”

The work of turning those numbers back into people continues.

The street that became a cemetery, and back again

On a quiet block of Chestnut Street in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, the dead lie beneath a streetscape that looks almost generically New England: clapboard houses, a line of parked cars, a strip of brick sidewalk.

The first hint that something else is happening here is the bronze figure of a woman, her body pressed against a granite wall, her face contorted in grief. Her arm stretches around the stone, fingers reaching for the outstretched hand of a man on the other side — a Black laborer in plain clothes, eyes fixed on the horizon. Their fingertips never quite touch.

This is Mother Africa and an enslaved African man, the twin entry figures of the Portsmouth African Burying Ground Memorial Park, unveiled in 2015. Beneath the paving stones and plantings around them are the reinterred remains of eight people whose bones city workers inadvertently unearthed during a sewer repair in 2003.

The archaeologists who studied them found four men, one woman, one child, and two individuals whose sex could not be determined — all of African descent, buried in simple coffins along what was once the edge of town. Historical research suggests that as many as 200 people were buried here in the 18th century, their graves gradually overrun by city expansion and then, quite literally, paved over.

For Valerie Cunningham, a longtime local historian who helped found the Portsmouth Black Heritage Trail, the discovery confirmed what she had been saying for years: that Black people were central to the city’s early story, even if their traces had been pushed underground.

Old maps and petitions tell part of that story. In 1779, a group of enslaved men in Portsmouth submitted a petition for freedom, demanding that the “name of slave may no more be heard in a land gloriously contending for the sweets of freedom.” Later research by the African Burying Ground Committee concluded that the grandparents and forebears of some of these petitioners were likely buried beneath Chestnut Street.

The memorial’s central axis — a line of engraved words from that petition, cut into the pavement — forces visitors to step across the language of freedom that the city’s Black residents articulated, even as their bodies were denied rest.

Unlike Zion and Sugar Land, the Portsmouth site is not a burial ground rediscovered in the 21st century so much as one slowly remembered. A simple marker went up in 2000; the full memorial took fifteen years of fundraising, design debates and delicate negotiations with neighbors who suddenly found themselves living atop a graveyard.

Here, the reckoning has focused less on legal ownership of the land than on the emotional and moral question of how a majority-white New England town chooses to inhabit a landscape where slavery was once routine.

Baldwin Hall and the campus beneath its feet

If Sugar Land and Zion expose the racial geography of Southern development, the graves under the University of Georgia’s Baldwin Hall show how little distance there is between a flagship public university and the labor of enslaved people who never set foot in a classroom.

In November 2015, construction crews renovating Baldwin Hall — a 1938 academic building in Athens — uncovered a human skull. Work stopped while archaeologists conducted a survey. Over the next several months, they exhumed the remains of 105 individuals from what had once been part of the town’s 19th-century cemetery.

Initial statements from university officials suggested the burials were of white European ancestry. Subsequent DNA testing told a different story: of 30 individuals whose genetic material could be analyzed, 27 were of African descent, likely enslaved or formerly enslaved people buried in a potter’s field at the edge of the original cemetery.

Black leaders in Athens argued that the remains should be reinterred in one of the city’s historically Black cemeteries, in consultation with descendant communities. Instead, the university followed the advice of the state archaeologist and reburied the individuals in Oconee Hill Cemetery, a historically white burial ground overlooking the campus.

The Guardian’s coverage at the time described the tension in stark terms: bones carried in the back of a pickup truck, students walking past protest signs, and a local pastor insisting, “They were owned in life, but UGA doesn’t own them in death.”

Unlike Sugar Land’s Sebe Froche or Tampa’s Anna Wyche, the people under Baldwin Hall remain anonymous. What we know of them comes from their bones — evidence of hard labor, malnutrition, and disease — and from the broader historical record of enslaved people who built and maintained the university town but were excluded from its institutions.

Still, their reappearance has changed the campus. Every tour that passes Baldwin Hall now walks over a contested memorial site; every conversation about diversity and inclusion at UGA takes place in a landscape where the ground itself speaks of inequality.

A national movement, and its limits

Taken together, these stories suggest not just a set of local scandals but a pattern.

In the Tampa area alone, the same reporter who helped confirm the Zion Cemetery went on to spur an investigation that located Ridgewood Cemetery, a pauper’s burial ground for African Americans and poor residents, under the athletic fields of King High School. There, radar surveys identified at least 145 coffins; the school district has since built a memorial by a pond on campus.

In Richmond, activists are pushing to protect the Shockoe Hill African Burying Ground from further encroachment, arguing that a cemetery that once held more than 22,000 people should not have to fight to be recognized as such.

In Bethesda, Maryland, the burial ground known as Moses Macedonia African Cemetery has become the focus of protests and lawsuits as developers seek to build over what descendants insist is sacred land.

These contemporary fights are unfolding against a backdrop of earlier rediscoveries, like the African Burial Ground in New York City — where, in the 1990s and early 2000s, Black New Yorkers forced the federal government to halt construction, consult descendant communities and eventually create a national monument.

They are also shaped by a legal framework still catching up to the scope of the problem. After years of advocacy by historians and members of Congress, the African American Burial Grounds Preservation Act now authorizes the National Park Service to fund research, documentation and preservation, creating a national program akin — in ambition, if not yet in resources — to the laws that protect Native American burial sites.

Yet, as The Guardian recently noted, Congress has not appropriated meaningful funding for grants, leaving communities to patch together private donations and local government support.

Meanwhile, the stakes of memory extend beyond the physical boundaries of any one cemetery.

In October 2025, in New Orleans, mourners gathered at Dillard University for a different kind of reburial: the skulls of 19 African Americans, taken from cemeteries in Louisiana in the 19th century and shipped to a German university for racist anthropological research, had finally been returned from Leipzig. Their remains, stripped even of the anonymity of a common grave, were laid to rest in coffins carved by Black artisans.

Those 19 people were not recovered from a recently rediscovered burial ground. But their story belongs to the same moral universe: a recognition that the remains of Black people have long been treated as disposable data, construction debris, or a problem to be moved out of the way — and that any serious accounting with American racism must extend to the dead.

The people under our feet

The pressure to build — more housing, more labs, more parking — is real. So is the fear, among cities and universities, that acknowledging a cemetery could trigger expensive delays or uncompensated obligations.

But to focus only on liability is to miss the question that Jeraldine Williams, and Meradeth Snow, and Valerie Cunningham keep pressing: What do we owe the dead?

Snow’s description of Burial 39 — of Sebe Froche’s broken wrist and mangled leg — is both forensic evidence and a kind of narrative repair, reassembling a life out of fragments the state tried to discard. Williams’s memorial for Anna Wyche asserts that a woman buried under public housing still has a claim on civic memory. Cunningham’s decades of historical work in Portsmouth locate Black lives and deaths in the very heart of New England’s built environment.

What ties these efforts together is not simply the recovery of names, although that matters. It is the insistence that the people under our feet had full human biographies — as parents and children, cooks and carpenters, soldiers and field hands, petitioners for freedom and, in the case of someone like Froche, would-be escapees from a system that tried to claim even their labor after death.

The national conversation about rediscovered Black burial grounds often frames them as sites of horror or scandal. They are that. But they are also, increasingly, places where communities are learning to tell a more complete story about themselves.

At Zion Cemetery, a bronze marker now stands where, not long ago, a chain-link fence and warehouse blocked the view. In Sugar Land, young people will soon walk from their classrooms to a memorial that forces them to reckon with the history beneath their school. In Portsmouth, passersby must literally step over the words of an 18th-century freedom petition to cross the street.

None of this undoes the original erasure. It does not restore the decades when families like the Wych e s and the Froches had no idea where their ancestors lay. But it does something subtler: it shifts the default setting of American memory, so that Black burial grounds are no longer assumed to be empty lots waiting to be built on.

On that February afternoon in Tampa, as Williams finished her poem, she bent down and placed flowers on the bare ground. No headstone marked the spot. Cars whirred by on nearby roads. Children shouted in the housing courtyard.

Still, for a moment, the old cemetery was visible again — not as a ghost story, but as a city of the dead whose residents are finally being called, if not fully by name, then at least into history.