KOLUMN Magazine

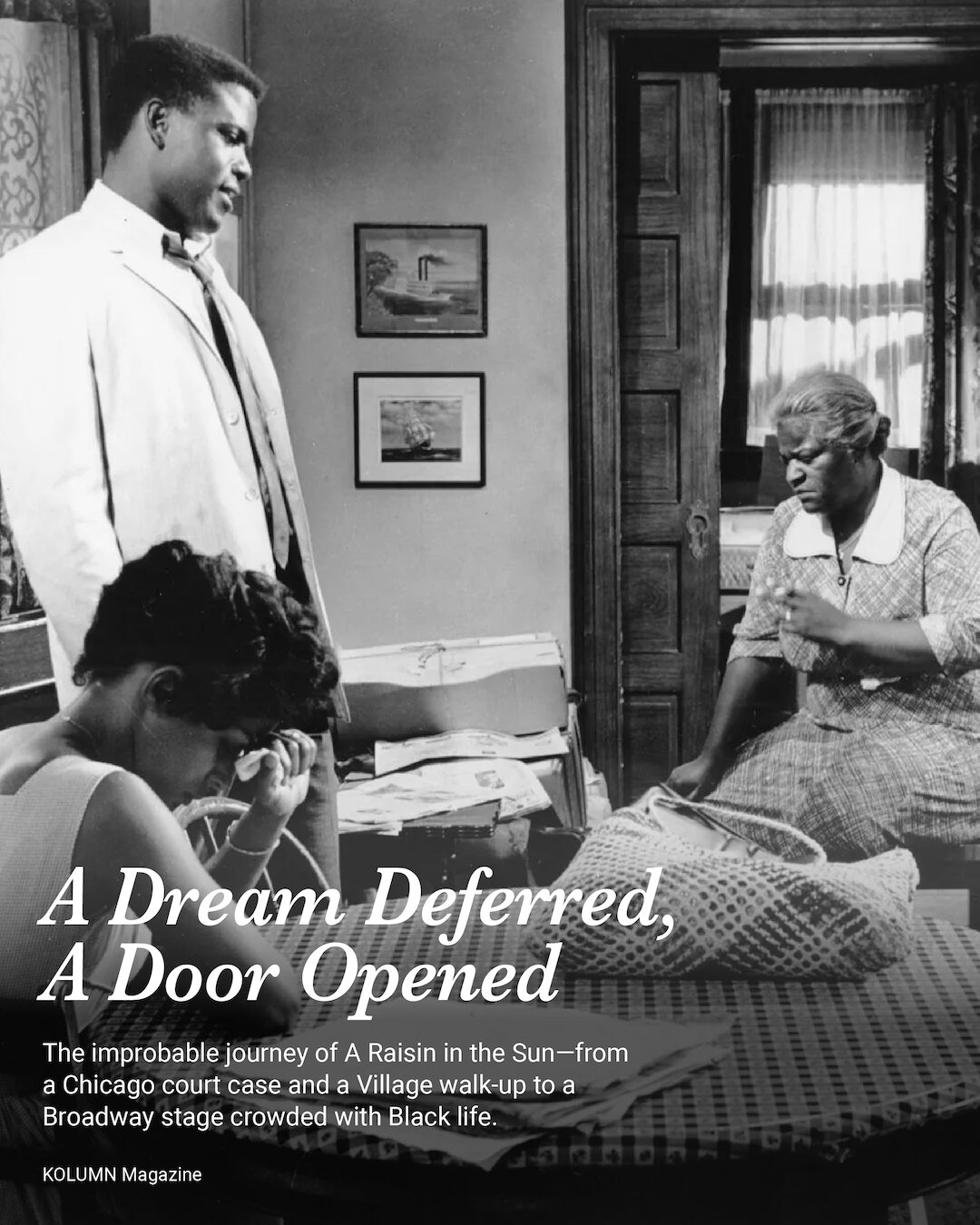

A Dream Deferred, A Door Opened

The improbable journey of A Raisin in the Sun—from a Chicago court case and a Village walk-up to a Broadway stage crowded with Black life.

By KOLUMN Magazine

On the night of March 11, 1959, Lorraine Hansberry stood in the dark at the back of the Ethel Barrymore Theatre, convinced her life’s work was about to die in front of her.

The previous evening’s preview of A Raisin in the Sun had landed with a thud. Some in the largely white audience had shifted uncomfortably in their seats. A few walked out. Hansberry and her producer, Philip Rose, had already rehearsed the conversation they’d have with investors when the show closed quickly and quietly.

Instead, after the curtain fell on opening night, the audience would not leave.

They stood, applauding, again and again. They demanded the playwright. Hansberry, 28 years old, small and wary, stayed in the shadows until Sidney Poitier—her leading man, the volatile center of the play—leapt off the stage, disappeared into the dark, and tugged her out into the light.

The ovation was not just for a hit play. It was for a new American theater in which a Black family’s cramped South Side apartment could be the center of the story, and in which an almost entirely Black cast would carry a Broadway drama for 530 performances.

This is the story of how that play—born out of a Chicago lawsuit, a Greenwich Village walk-up, and a producer’s improbable conviction—fought its way to Broadway, and how the people who embodied the Youngers were chosen, one by one.

The lawsuit that became a living room

Hansberry did not have to imagine the central conflict of A Raisin in the Sun—a Black family’s attempt to move into a white neighborhood and the hostility that greets them. It had been the story of her own childhood.

In the 1930s, her father, Carl Hansberry, a prosperous real-estate broker sometimes called the “Kitchenette King” for the cramped apartments he managed, moved the family into a white neighborhood on Chicago’s South Side, breaking a restrictive racial covenant. White residents fought the encroachment in court and on the street. Hansberry later recalled her mother patrolling the home at night with a loaded gun.

The legal battle that followed, Hansberry v. Lee, went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which in 1940 invalidated the particular covenant used against the family and helped weaken legal support for housing segregation nationwide.

Two decades later, that history would be distilled into a single figure at a kitchen table: Karl Lindner, a mild-mannered representative of the Clybourne Park Improvement Association, offering the fictional Younger family a buyout to stay out of his white neighborhood.

Before Hansberry found that scene, though, she had to find her way to the theater.

From Freedom newspaper to the Village

In 1950, Hansberry left Chicago for New York. She went not to Broadway but to the newsroom.

She went to work for Freedom, a radical Black newspaper edited by Paul Robeson and staffed by an extraordinary roster of writers and activists, including W.E.B. Du Bois. There she covered evictions, colonial struggles abroad, union organizing at home. She learned the compressions and clarities of deadline prose—and sharpened her politics.

In the evenings, she wrote.

Hansberry lived in a small Greenwich Village walk-up with her husband, songwriter and activist Robert Nemiroff, whom she had met at a protest against racial discrimination at New York University. They spent their wedding night demonstrating against the execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg.

On weekends, while Nemiroff played his songs in clubs, Hansberry worked on a play then called The Crystal Stair, after another line from Langston Hughes. It was about a Black family on Chicago’s South Side arguing about what to do with a $10,000 life-insurance check—whether to buy a house, pay for medical school, or chase a riskier entrepreneurial dream.

She drew not only from her family’s fight against segregation but also from the crowded tenements she had known and the arguments she’d overheard in kitchens and hallways. As she later told an interviewer, she wanted to put “the totality of Black life” in one room.

What she did not yet have was a producer.

Philip Rose goes looking for a family

Philip Rose’s route to Broadway began in living rooms, too—just not his own.

In the 1940s, Rose, the son of poor Jewish immigrants, worked as a travelling record salesman, lugging jazz and rhythm-and-blues discs from store to store across the East Coast. His job brought him into Black neighborhoods and homes he’d never otherwise have entered. He listened as customers talked about police harassment, slumlords, and the omnipresent “color line.”

The experience shook him. As he later wrote in his memoir You Can’t Do That on Broadway!, he wanted to put a truthful Black story on a mainstream New York stage—a story that wasn’t a musical revue or a minstrel holdover, but a serious drama about ordinary people.

In the mid-1950s, Rose read some of Hansberry’s work and heard she was developing a play about a Black family and a contested house. He tracked down the script of The Crystal Stair and was floored. The language, the humor, the anger—all the things he’d heard in those living rooms—were there.

Rose optioned the play and, with partner David Cogan, committed to producing it, even though nearly everything about the project made commercial investors nervous. With all but one character Black, it was assumed that white Broadway audiences would stay away.

It took Rose and Cogan roughly a year—and in some accounts closer to 18 months—to assemble the backing. In the end, about 150 small investors put in money, a patchwork of belief that the play might matter more than the odds suggested.

Along the way, the title changed. Hansberry and Rose settled on another Langston Hughes image: a dream deferred that “dries up / like a raisin in the sun.”

What they needed next was a director—and a family.

Saturdays with Lloyd Richards

The director Rose chose, Lloyd Richards, had been waiting for a script like this one.

Richards, a Canadian-born Black actor and director, had spent years navigating a theater world that rarely let Black artists move beyond stereotypes or servant roles. He understood both the politics and the craft that Hansberry’s script demanded.

For about two months, the two met on Saturday afternoons to hammer the play into shape. Hansberry had written two possible endings and was stuck somewhere in the third act. Together they discussed structure, pacing, and where the story’s moral center truly lay.

Some potential backers wanted the play to center the saintly, plant-tending mother, Lena Younger. Others argued that the story belonged to Walter Lee, the mercurial son who wants to use the insurance money to buy into a liquor store. The question of emphasis would shape the casting.

Richards’s other challenge was practical. As he later recalled, Raisin was considered a huge gamble: a serious Broadway drama with a largely Black company, written by a Black woman, directed by a Black man. “Raisin in the Sun was a big risk,” he said. “I was putting a lot on the line.”

He would need actors whose talent could quiet doubts the moment they walked onstage.

Finding Walter Lee: Sidney Poitier’s gamble

By the time A Raisin in the Sun was ready to cast, Sidney Poitier was no unknown.

He had broken through in films like Blackboard Jungle and The Defiant Ones, and he had already become, in the eyes of many white critics, the acceptable face of Black male respectability: elegant, contained, controlled. Hansberry’s Walter Lee was something else—volatile, impulsive, trapped between bitterness and hope.

Rose and Richards wanted Poitier anyway.

The actor hesitated. In his memoir, he would later describe the tug-of-war over whether the play belonged to Lena or Walter, and his own anxieties about returning to the stage in such an exposed part. But the script’s power—and the chance to embody a Black man whose rage and vulnerability were fully human—pulled him in.

Poitier’s casting sent a signal to investors that Raisin was no small Off-Broadway experiment. It also set the emotional temperature in the rehearsal room. His Walter Lee prowled the apartment, coaxing and bullying his family, reaching for dignity and often falling short. The play might be an ensemble piece, but Poitier’s intensity made clear that one of its beating hearts was the son.

The matriarch: Claudia McNeil’s rootedness

If Poitier supplied the spark, Claudia McNeil provided the ground.

McNeil had worked as a singer and stage actor, but she was hardly a Broadway star. What she brought into the audition, colleagues later recalled, was an unadorned authority that made the Younger family’s worn furniture and peeling wallpaper feel like a kingdom she still intended to rule.

As Lena “Mama” Younger, McNeil carried both the memory of the South and the moral weight of the family’s decision: whether to use the insurance money to buy a house in a hostile neighborhood or to indulge her son’s business ambitions. Her performance would earn a Tony nomination—and help anchor audiences who might otherwise have dismissed the Youngers as “too angry” or “too specific.”

Hansberry, who knew something about mothers with guns and mortgages, had written Mama with tenderness and steel. McNeil gave her a body, a voice, and a silence that could stop Walter Lee mid-rant.

Ruby Dee and the quiet radicalism of Ruth Younger

For Ruth Younger, the weary wife caught between mother-in-law and husband, Hansberry and Richards turned to Ruby Dee.

By 1959, Dee was already respected as both an actor and an activist. Alongside her husband, Ossie Davis, she had marched, organized, and spoken out against segregation. Onstage, she had a gift for small, precise gestures that spoke volumes.

As Ruth, Dee moved through the Youngers’ apartment like a woman counting every nickel and every step: cooking, ironing, absorbing insults, dreaming of a little yard where her son might play. Famous photos from the production show her leaning into Poitier’s chest, arms wrapped around him, as if trying to hold together a man and a world coming apart.

In interviews years later, Dee would describe seeing the play as a kind of mirror held up to audiences who had never before watched a Black husband and wife argue about money and dreams in the same way their white neighbors did. The casting, she said in a PBS American Masters segment, was “groundbreaking” precisely because the characters were not symbols but people.

The younger generation: Diana Sands, Ivan Dixon, and Louis Gossett Jr.

If Poitier, McNeil, and Dee gave the play its generational conflict, the younger cast members gave it its forward lean.

Diana Sands, cast as Beneatha Younger, brought volatility of another kind. Beneatha is the college-educated younger sister who wants to become a doctor and is impatient with both assimilation and sentimental notions of Africa. Sands played her with restless wit, questioning not only her suitors but also her own family’s compromises.

As Joseph Asagai, the Nigerian student who challenges Beneatha’s ideas about identity and liberation, Ivan Dixon added warmth and political edge. Lonne Elder III, as Walter’s friend Bobo, gave heartbreaking voice to the cost of misplaced trust when the investment money disappears. John Fiedler, the lone white actor in the principal cast, played Karl Lindner with a meekness that made his racism all the more chilling.

The role of George Murchison—the wealthy, assimilationist suitor Beneatha can’t quite stomach—went to a 20-something actor whose life would be altered by the call: Louis Gossett Jr.

Gossett had been on track to play professional basketball. He had a scholarship to NYU and was training with the New York Knicks when the phone rang. Lorraine Hansberry was on the line. She wanted him in Raisin—and the part came with a $700 weekly per diem, more than many pro athletes were making. “I put the basketball down, and the rest is history,” he later recalled.

Onstage beside Poitier, Gossett embodied a different Black male possibility: polished, wealthy, dismissive of what he saw as his community’s provincialism. The casting turned an ideological debate about assimilation versus pride into a romantic triangle, played out in narrow hallways and crowded living-room corners.

And then there was the smallest member of the family.

Glynn Turman, a child actor, played Travis Younger, the boy who sleeps on the couch and waters Mama’s struggling plant. In his wide eyes, audiences could see what all the arguing was ultimately about: a future place to stand.

A risky road to Broadway: New Haven, Philadelphia, Chicago

Even with the cast in place, A Raisin in the Sun was far from guaranteed a Broadway home.

Throughout 1958, the company took the play on the road in a series of out-of-town tryouts—first in New Haven at the Shubert Theatre, then in Philadelphia, then in Chicago. Houses were sometimes half-empty. Some nights, audiences were puzzled; others, electrified.

Hansberry and Richards kept revising. They tightened scenes, sharpened jokes, and recalibrated the balance between Walter Lee’s rage and Mama’s steadiness. Critics in the early cities were cautiously respectful, if not ecstatic.

Then came Chicago.

At the Blackstone Theatre, the play landed in a city whose own racial geography echoed the Youngers’ story almost block for block. Claudia Cassidy, the formidable critic of the Chicago Tribune, wrote a rave so unexpected that Rose would later credit it with changing the show’s fate.

Suddenly, New York theater owners who had been wary of booking a “race play” were returning Rose’s calls. The Ethel Barrymore Theatre became available. Investors, once resigned to perhaps losing their money for a worthy cause, began to imagine a hit.

Still, the anxiety didn’t dissipate. On the train to New York, some company members worried aloud about how Broadway’s predominantly white critics would receive a living room full of Black quarrels, jokes, and disappointments that didn’t conform to liberal uplift narratives.

Opening night and the sound of a door opening

What happened instead has entered theater lore.

On March 11, 1959, A Raisin in the Sun opened at the Ethel Barrymore. Reviews the next morning were strong. Brooks Atkinson of The New York Times praised the play’s humanity; Black newspapers hailed its authenticity. The New York Drama Critics’ Circle would soon name it the best American play of the year.

More important than the awards was who came to see it.

For the first time in modern memory, Black audiences turned out in large numbers for a straight Broadway play, not a musical revue—crowding the balcony and lining up at the box office. Director Lloyd Richards later noted that Raisin was the first play to which “large numbers of black people were drawn” on Broadway, and that white audiences seemed startled, then moved, to find themselves watching a Black family that looked nothing like the caricatures they had grown used to.

The production ran for 530 performances, transferring in October 1959 to the Belasco Theatre and closing in June 1960. It received four Tony nominations—for best play, best direction, and acting nods for Poitier and McNeil—and set a new record for the longest-running Broadway play written by a Black American.

In 1961, most of the original cast—Poitier, Dee, McNeil, Sands, Gossett—reprised their roles in a film adaptation with a screenplay by Hansberry, carrying the Younger family into cinemas around the world.

Decades later, the play’s impact still reverberates. In 1983, New York Times critic Frank Rich wrote that A Raisin in the Sun had “changed American theater forever,” helping to prove that Black characters could be written—and received—as complex, ordinary, fully human protagonists. In 2016, The Guardian’s Claire Brennan called it “as moving today as it was then,” a play whose craft and power continue to challenge audiences.

Casting as politics

Looking back, it is easy to see A Raisin in the Sun as inevitable: of course Hansberry would write it, of course Poitier and Dee and McNeil would star in it, of course it would win prizes and be taught in classrooms.

At the time, nothing about it was inevitable.

Every major choice—from Rose’s decision to risk his reputation on a serious Black family drama, to Richards’s insistence that the production be both artistically and politically uncompromising, to Hansberry’s stubborn refusal to soften her characters for white comfort—ran against Broadway wisdom.

So did the casting.

In a short documentary segment years later, Poitier, Dee, and Richards would remember that they understood, even in rehearsal, that they were not just making a play; they were making an argument about who could be seen at the center of an American story.

Hansberry, who died in 1965 at just 34, did not live to see all the doors her play opened—or the still-unfinished work of keeping them open. But the path Raisin cut to Broadway remains a map for artists and producers pushing new stories forward: the long fund-raising meetings, the bruising tryouts, the arguments in rehearsal about whose dream is deferred and whose is finally, tentatively, realized.

On that first night, when Poitier pulled Hansberry into the glare of the footlights, it wasn’t only the playwright the audience was applauding.

They were cheering an ensemble of Black actors who, by stepping into the cramped living room of the Younger family, had made room on Broadway for themselves—and for generations to come.