KOLUMN Magazine

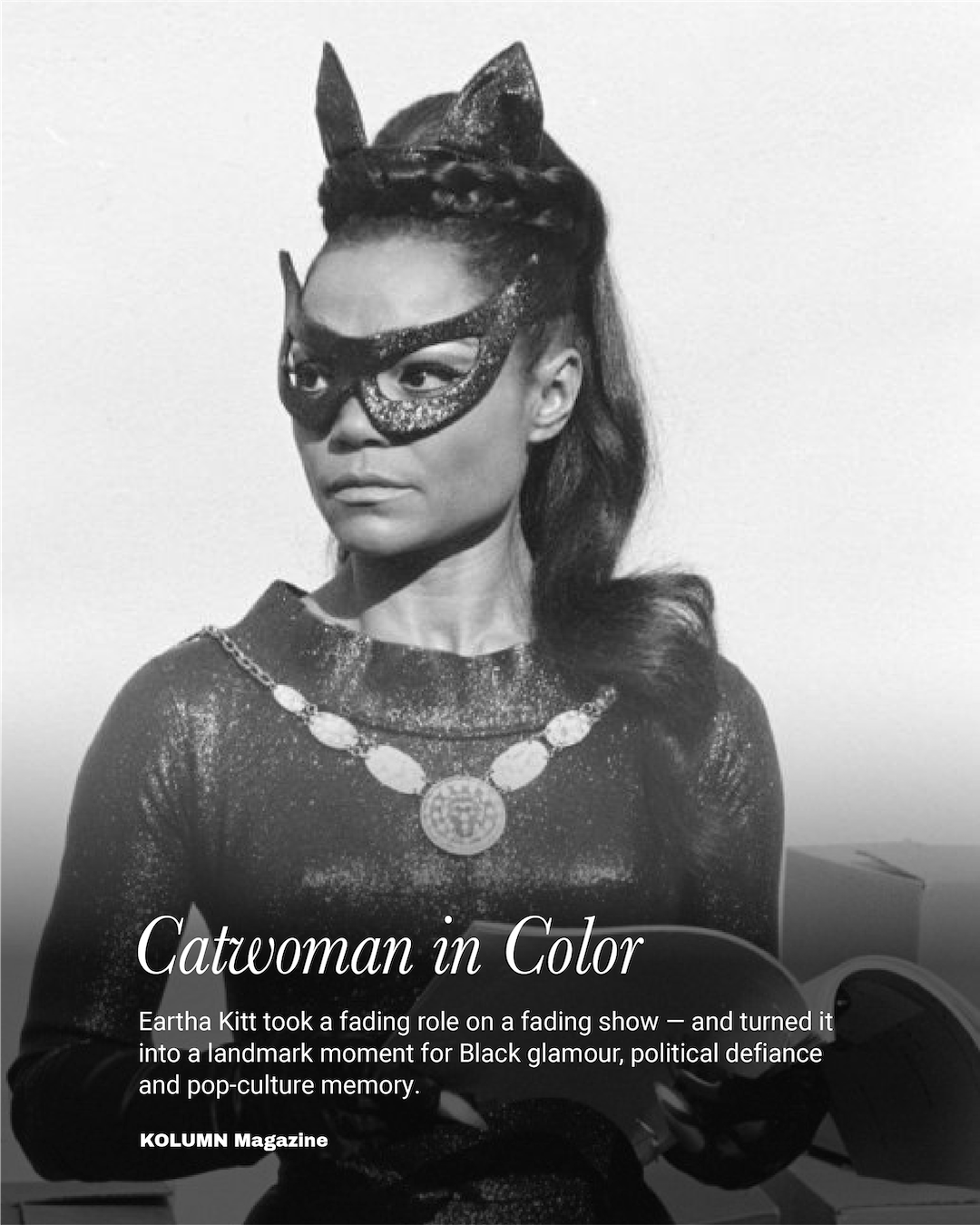

Catwoman

in Color

Eartha Kitt took a fading role on a fading show — and turned it into a landmark moment for Black glamour, political defiance and pop-culture memory.

By KOLUMN Magazine

On a winter evening in 1967, somewhere between the dinner dishes and bedtime, American living rooms flickered with something they had never quite seen before: a Black woman in a liquid-black catsuit, eyes rimmed in glittering mask, standing nose-to-nose with Batman and calling him “purrr-fect” like a threat.

The actress was Eartha Kitt. By the time she slinked into the third and final season of ABC’s Batman, she was already famous — a chanteuse who purred through “Santa Baby,” a nightclub star whom Orson Welles had once introduced as “the most exciting woman in the world.”

But Catwoman turned out to be something else: a lifeline at a precarious moment in her career, a quietly radical piece of television casting, and a role that would follow her for the rest of her life.

The nine lives before Gotham

Kitt’s journey to Gotham began far from Hollywood. Born Eartha Mae Keith on a cotton plantation in South Carolina in 1927, she was the mixed-race daughter of a Black and Cherokee mother and a white father she never knew. She later recalled being rejected for her light skin in Black communities and reduced to “poor Black girl” by whites, an early lesson in how race could be weaponized from every side.

At 16, she escaped into art — earning a scholarship to study with choreographer Katherine Dunham and eventually touring the world with the Dunham dance company. In Paris clubs and New York cabarets she discovered the persona that would make her a star: half panther, half comedian, her vowels stretched into a purr, her stage walk a controlled prowl.

By the early 1950s, she had a hit album with RCA, songs like “Monotonous” and “I Want to Be Evil,” and a reputation as a “sex kitten” — a label she leaned into with a wink. Welles cast her in his stage production Time Runs and, by many accounts, delighted in her danger. She made films, cut records, toured relentlessly.

Yet fame proved cyclical. By the mid-1960s the U.S. music landscape had shifted. British rock and Motown dominated the airwaves. Kitt remained a draw in nightclubs and on European stages, but her American profile had dimmed. In a later interview with the Television Academy, she described 1967 bluntly: “I was in dire need of tremendous help… like a starving cat I had to find a way to survive.”

The “bone” thrown to her, as she put it, was a campy superhero show in desperate need of a villain.

Batman, ratings trouble and a missing Catwoman

When Batman premiered in 1966, it landed like a pop-art explosion. Shot in bright color, tilted camera angles and punctuated by on-screen “BAM!”s and “POW!”s, the series quickly became appointment television for children and a winking joke for adults.

One of the show’s breakout stars was Catwoman, played by Julie Newmar. Tall, arch and impossibly limber, Newmar’s Catwoman grew over two seasons into more than a villain. Episodes lingered on a flirty, unfulfilled romance between the cat burglar and Adam West’s square-jawed Batman. In the second season, she was almost more love interest than antagonist.

Behind the scenes, though, the show was already wobbling. Ratings dipped in season two, and ABC responded with a flurry of tweaks — adding Batgirl, shuffling villains, tinkering with tone. When it came time to plan the third season in 1967, the producers faced an unforeseen problem: Newmar was no longer available. She had committed to a major role in the Western film Mackenna’s Gold, a shoot that would overlap with Batman’s production schedule.

Recasting wasn’t unusual on Batman. The show had already swapped out actors for the Riddler and Mr. Freeze without much fuss. But Catwoman was different. She was an icon inside an icon, smack in the middle of a show still reliant on marquee villains to juice its ratings. The search for a replacement, one writer later noted, made Catwoman “one of the most sought-after positions in Hollywood” that season.

It was executive producer William Dozier who fixed on Eartha Kitt.

“She was a cat woman before we ever cast her”

The choice, in hindsight, seems almost obvious. Kitt had built a decades-long career out of being feline. Her eyes, producer Charles B. FitzSimons recalled, were “cat-like,” her singing carried a sly, meowing quality, and she moved like “a cat woman” long before anyone zipped her into spandex. Casting her, he said, felt like a “wonderful off-beat idea” — and, crucially, an intentionally provocative one.

Provocative, because Kitt was Black.

In 1967, network television was only beginning to reckon with what it meant to show Black actors in roles that weren’t maids, comic sidekicks or background extras. Star Trek’s Nichelle Nichols had just blazed a trail on the bridge of the Enterprise. Bill Cosby was breaking ground in I Spy. But prime-time still had very few Black women in positions of glamour, power and unambiguous desirability.

Catwoman was all three.

According to later accounts, when ABC announced Kitt’s casting, some Southern affiliates were furious. They were used to seeing Black characters as peripheral; the idea of a Black woman circling around a white male hero with clear sexual charge made them nervous.

The producers held their ground on the casting — but compromised on the romance. Where Newmar’s Catwoman had nearly kissed Batman more than once, Kitt’s would receive no such lingering close-ups. A fan-history of the show notes flatly that the “sexual attentions” between Batman and Catwoman vanished once Kitt took over, in part because interracial flirtation was considered unacceptable for early-evening network television. Instead, writers gently nudged Batman’s suggested love interest toward Batgirl.

Kitt, for her part, approached the job practically. In a biography excerpted by MeTV, she joked that playing a cat didn’t require research: “Something is in you that says you are that character.” The role, she later said, was “so much fun” — but it was also survival. The exposure helped her “grow back into being a successful name again.”

On June 14, 1967, she signed on for the third season. In early July, she stepped onto the soundstage in full costume.

Reinventing Catwoman

Unlike many actors taking over an established role, Kitt didn’t shadow her predecessor. In fact, she later said she’d never seen Newmar’s Catwoman before agreeing to play the character. That ignorance turned out to be a kind of freedom. She wasn’t mimicking anyone; she was doing Eartha Kitt.

Her Catwoman debuted in the episode “Catwoman’s Dressed to Kill,” which aired in December 1967. The plot is typical Batman: Catwoman targets Gotham’s fashion world, kidnaps models and plots to humiliate rivals at a charity pageant. But the performance is something else. Kitt speaks with clipped, almost regal diction, her R’s rolled into that famous purr. She laughs rarely and never coquettishly. There is no fluttering over Batman; there is only irritation that he exists.

Over the course of five episodes — “Catwoman’s Dressed to Kill,” “The Funny Feline Felonies,” “The Joke’s on Catwoman,” “The Ogg Couple” and “The Bloody Tower” — she leans harder into villainy than her predecessors. Her Catwoman runs an elaborate “Catlair,” drives a futuristic “Kitty Car,” captures Batgirl and threatens to kill her. At times she seems less a temptress than a CEO who happens to enjoy jewel theft.

Castmates felt the shift. Yvonne Craig, who played Batgirl, later recalled that Kitt was “perfect because she was very cat-like anyway” — and, Craig added, closer to her own height, which made fight scenes more believable than with the towering Newmar.

Alan Napier, the veteran English actor who played Alfred, admitted he still favored Newmar’s version but called Kitt “marvelous,” even as he noted she “complain[ed] a lot on the set” — a comment that can read, depending on one’s angle, as a dig at a temperamental star or a nod to an older performer watching a Black woman assert herself in a white-dominated workplace.

Off-screen, the casting rippled through audiences. In a Washington Post multimedia history of Black superheroes, writers later singled out Kitt’s 1967 Catwoman as one of the earliest examples of a Black performer embodying a comic-book character on screen. The article noted how her performance trimmed some of the overt sexuality of the earlier Catwoman but left her just as formidable as a villain.

For Black viewers, particularly children, the sight of a glamorous Black woman trading verbal blows with Gotham’s most powerful men carried its own charge. Decades later, Kitt’s daughter, Kitt Shapiro, remembered nine-year-old kids watching with pride: this was 1967, she pointed out, and there simply weren’t women of color in skintight bodysuits sparring as equals with white male leads on national TV.

Catwoman vs. the White House

Ironically, just as Batman was helping restore Kitt’s profile, a very different piece of political theater would nearly erase it — at least in the United States.

On January 18, 1968, First Lady Lady Bird Johnson invited about 50 “women doers” to a White House luncheon on youth crime. Kitt was on the guest list. What happened next has been retold in The Washington Post, the New Yorker and the White House Historical Association: when Johnson asked the assembled women about juvenile delinquency, Kitt stood up and tied it directly to the Vietnam War. Young people rebel and turn to drugs, she said, because their brothers are being sent overseas “to be shot and maimed.”

The remarks made front-page news and infuriated the Johnson administration. According to later reporting, Kitt’s U.S. bookings dried up almost overnight; she spent the next several years working primarily in Europe and Asia.

The timing is striking. When fans remember Kitt’s Catwoman, they are often remembering a compressed period — December 1967 through early 1968 — when she was simultaneously America’s most visible Black super-villain and one of its most outspoken critics of the Vietnam War. Within months of her last Batman episode, she was — in practice if not officially — blacklisted.

On fan sites, biographies of Kitt linger on the sense of rejection she described during that exile, quoting her observation that after the White House incident she felt “rejected artistically, emotionally and personally,” as if her country had given her away just as her mother once had.

And yet the reruns kept airing. Children who discovered Batman in syndication in the 1970s or ’80s often encountered Kitt first as Catwoman, long before they learned about the woman who shouted down the First Lady.

Living with Catwoman

For the rest of her life, Kitt’s other achievements — the nightclub triumphs, the Tony nominations, the Grammy nods, the activism — had to share space with the leather-clad thief she played in five episodes of a camp show.

She seemed alternately amused and exasperated by this. In a 1998 profile in The Washington Post, she noted that people would point her out to their children with a kind of delighted recognition: Catwoman, Eartha Kitt! They rarely mentioned whoever else had played the role.

When the Golden Globes site revisited the long line of Catwomen in 2022, it quoted Kitt’s Television Academy interview at length. Playing a “sexy Catwoman” had been a dream, she said; the part was fun, but it was also crucial, helping her claw back into the center of American pop culture. Her name recognition decades later, she acknowledged, still rested heavily on those Gotham episodes.

By the 1990s, she was reflecting more openly on the racial politics of the casting. On a 1992 talk show appearance, she pointed out that being the first Black Catwoman on screen felt “pioneering” at the time and that young viewers of color were “very proud” to see someone who looked like them in a role where her race was not commented on within the show.

That contradiction — race both invisible in the script and hyper-visible in the culture — is part of what makes her Catwoman so resonant. Within the show’s universe, no one mentions that Catwoman is Black. Outside of it, Southern stations complained, producers quietly rerouted Batman’s romantic attention, and Black kids saw a fantasy version of themselves onscreen.

Meanwhile, Kitt’s performance continued to be reassessed. A fan-curated Batman site praises her for restoring some of the character’s ruthlessness after a more romantic turn in season two, describing her Catwoman as more serious and dangerous. In jazz magazines and obituaries, writers remember being transfixed by her in 1967, watching as she “purred” into their consciousness from living-room TVs.

When later Black Catwomen arrived — Halle Berry’s much-maligned 2004 film, then Zoë Kravitz’s acclaimed turn in The Batman — journalists repeatedly traced their lineage back to Kitt. GQ, in a short history of the “Black Catwoman,” noted that nothing intrinsic to the character’s backstory ever demanded whiteness and pointed to Kitt’s 1967 performance as proof that audiences could accept a Black woman under the mask, even in an era that insisted on toning down her sexuality.

For Kitt, that seemed to be enough. “I love doing the character,” she told one interviewer in 2006, asked if she’d ever return to the role. “I didn’t have to think about it… I am a cat.”

The lasting purr

The pop-culture image of Catwoman has shifted constantly over eight decades: a jewel thief in the comics, a dominatrix in the Burton films, a wounded antihero in Nolan’s universe, a noir-tinged ally in Reeves’s. But the 1960s television incarnation — campy, low-budget, constrained by network standards and a six-day shooting schedule — still looms large.

Within that narrow frame, Eartha Kitt managed an audacious act of self-insertion. She turned a recast part into a reclamation: a work-for-hire job taken, by her telling, to survive, that nonetheless forced prime-time America to confront a new kind of leading woman. Not a maid, not a sidekick, not a tragic victim — a villain who enjoyed herself, whose body language spelled power, whose very presence challenged where a Black woman could stand and what she could demand.

In later years, Adam West would reminisce fondly about “my three Catwomen,” and Robin actor Burt Ward politely refused to pick a favorite, insisting that each brought something special. The audience, though, has been less diplomatic. In message boards and nostalgia blogs, fans still argue — Newmar’s statuesque elegance versus Kitt’s feral intensity — but even those who prefer another portrayal concede that Eartha’s take was singular.

She was, as FitzSimons said, a cat woman before they ever cast her. Batman simply gave her a playground in which to prowl — and, in the process, gave television one of its earliest super-powered images of Black femininity in full, unapologetic command.