Walls That

Remember Us

How Black-run museums and art galleries turn family stories into a public record—and why that matters now.

By KOLUMN Magazine

On a bright fall morning in Washington, D.C., the bronze-clad walls of the National Museum of African American History and Culture catch the light like an ember. Inside, the air feels unusually hushed for a space that has already welcomed more than ten million people since it opened in 2016.

Near the exhibit on the Middle Passage, a Black grandmother stands between her teenage grandson and a glass case holding rusted iron shackles. He is tall and lanky, in a Howard University sweatshirt; she is small, her hand wrapped tight around his wrist as though she is steadying both of them. He reads the label silently. Then, almost reflexively, he steps closer to her.

“We learned about slavery,” he says at last, his voice low. “But not like this.”

It is a familiar scene in Black-centric museums and galleries across the United States: someone encountering, often for the first time, the physical proof that their history is not an elective, not a sidebar, not extra credit—but the spine of the American story.

These institutions—national museums on the Mall, storefront galleries on neighborhood streets, community-run archives in repurposed churches—do something that mainstream museums long failed to do. They place Black life at the center of the frame. They insist that Black people are not footnotes to someone else’s narrative, but the authors of their own.

“Black history museums began to exist in the mid-20th century as a response to Black Americans not being in existing museums,” says Joy Bivins, director of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem, describing a landscape in which Black people were either omitted or caricatured in dominant institutions.

That absence didn’t just distort the past; it shaped how generations of Black Americans understood their place in the country. The rise of Black-centric museums and galleries has been, in many ways, a campaign against that erasure—an ongoing fight to reclaim memory, space, and imagination.

“We Were Never Meant to See Ourselves Here”

For much of the 18th and 19th centuries, as historians and museum curators assembled a narrative of the young United States, a pernicious belief took root in the white imagination: that Black people had no history worth preserving. The achievements, intellectual traditions and everyday lives of African Americans were either ignored or actively suppressed.

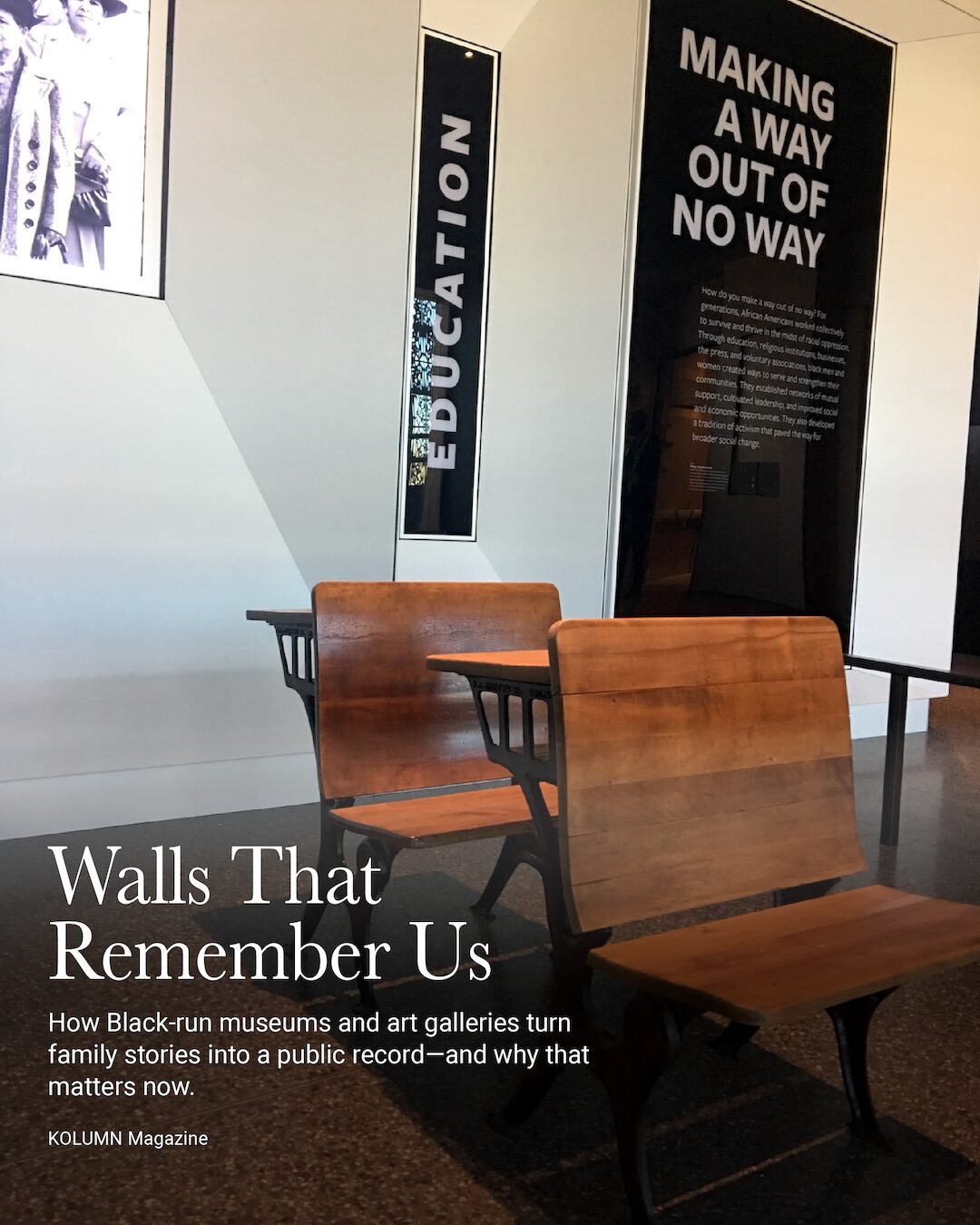

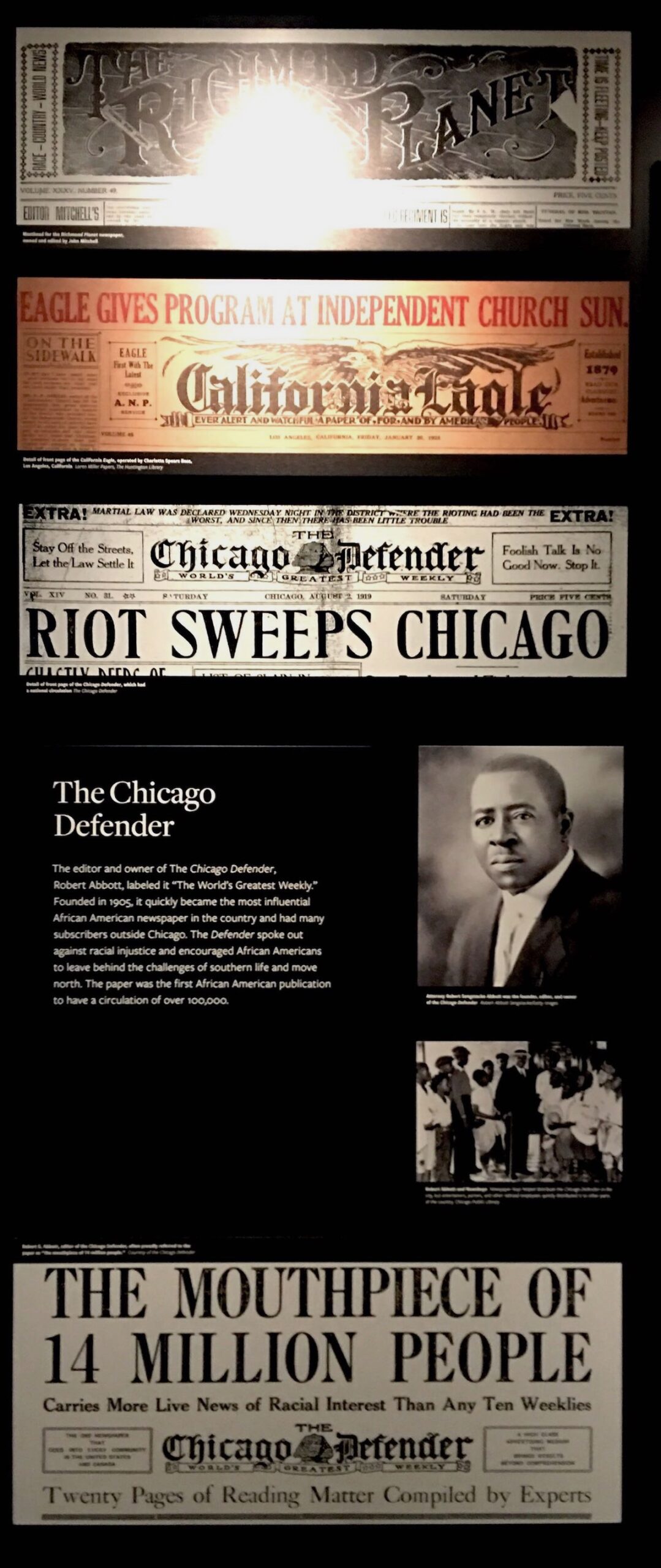

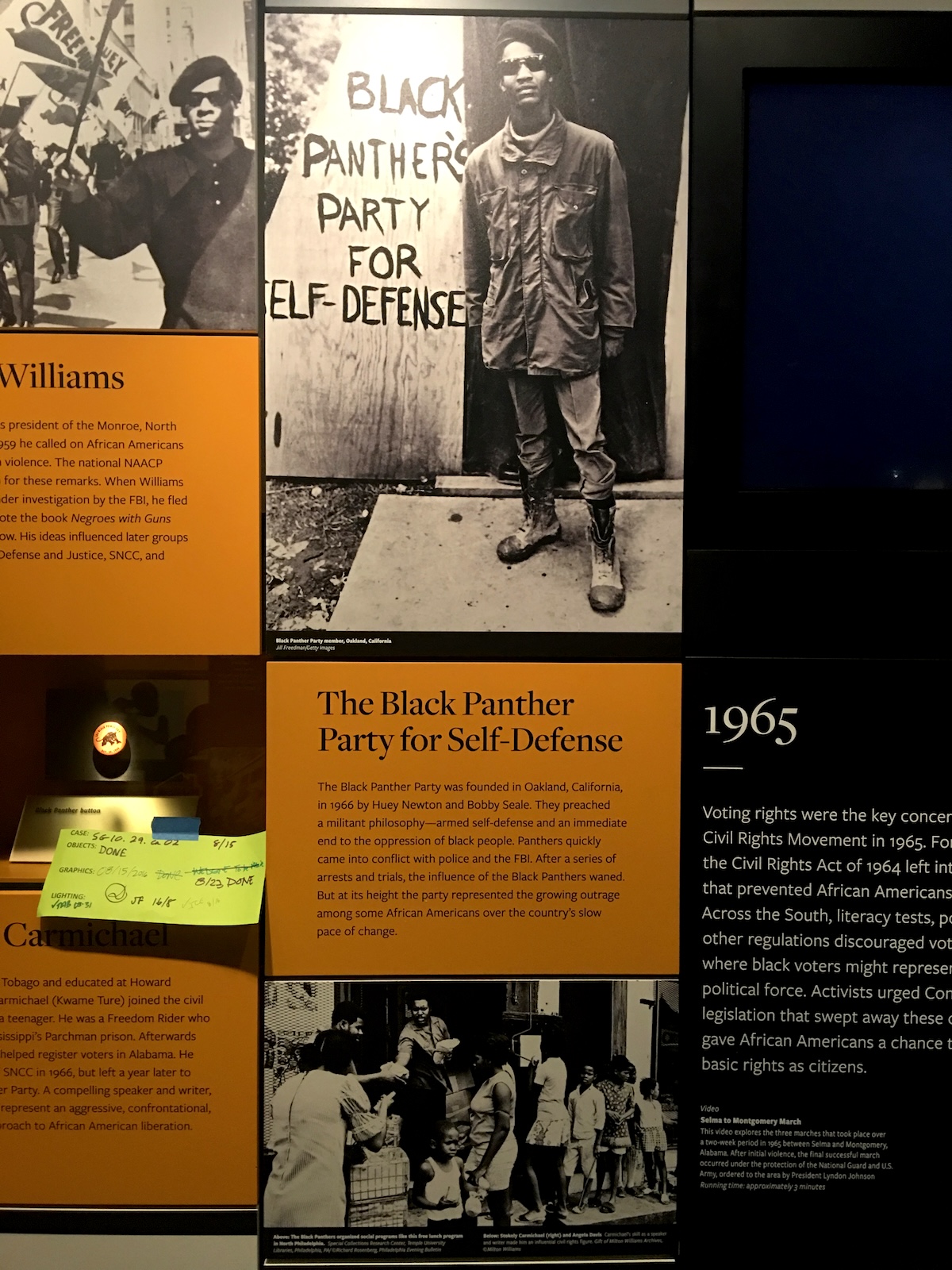

By the mid-20th century, as Black communities organized through the Civil Rights and Black Power movements, a different vision emerged. African American museums grew out of local struggles over school curricula, public monuments and segregated cultural institutions. They were, as one historian put it, “cornerstones of the Black Power movement,” places that preserved history and shared stories “through the lens of Black America.”

Community leaders converted homes, churches and storefronts into spaces where Black art, artifacts and archives could be safeguarded. They collected what others had deemed disposable: funeral programs, church fans, newspaper clippings, freedom papers, photographs of Black soldiers in Union uniforms, ticket stubs from segregated theaters. The collections were modest; the ambitions were not.

African American museums, the Urban Institute later argued, would come to “restore public memory” by chronicling not only slavery and Jim Crow, but also labor struggles, women’s organizing, civil rights, Black Power and Black Lives Matter. In the process, they became “important community assets” that engage young people and anchor neighborhood life.

In other words, they were not just repositories of objects; they were arguments. Arguments against amnesia. Arguments that Black people were central to the nation’s history and, crucially, its future.

The National Stage: A Bronze Crown on the Mall

No institution embodies that argument more visibly than the National Museum of African American History and Culture, or NMAAHC, the Smithsonian’s youngest museum and its first devoted entirely to Black life.

The very existence of the museum is the product of a century-long struggle. Black advocates began pushing for a national museum in the early 20th century; legislation was introduced in Congress at least a dozen times before finally passing.

Since opening in 2016, NMAAHC has become both pilgrimage site and public square. By 2021, it had welcomed more than eight million visitors; by 2023, it celebrated its ten-millionth in-person guest—families from Prince George’s County, school groups from Iowa, tourists from Berlin and São Paulo.

The building itself is a monument. Designed by a team including David Adjaye, its three-tiered corona—clad in a bronze-colored metal lattice that references West African art and ironwork crafted by enslaved Black artisans in the American South—rises just steps from the Washington Monument. The architecture quietly reverses an old hierarchy: the nation’s founding obelisk at one end, the story of the enslaved whose labor made that founding possible at the other.

Inside, visitors descend below ground to galleries that trace the history of slavery, Reconstruction and Jim Crow before rising, floor by floor, through exhibits on popular culture, politics, sports and the Black Lives Matter movement. The structure demands active participation: you start in darkness and move upward into light, carrying the weight of what you’ve just seen.

For Black visitors, the experience can be something like a reckoning. For others, it can be a revelation. Museum leaders have noted that visitors are often willing to engage with “difficult parts of American and global history,” suggesting a public appetite for confronting hard truths.

At street level, the museum plays a quieter but no less important role: it normalizes Black presence on the National Mall. School groups pose for photos on its steps. Elders sit on benches beneath its overhang, resting after hours in the galleries. Couples wander out after a day inside, blinking in the sunlight, their conversations threading the private and the political—about what it means to see, on such a grand stage, proof that Black life has always been more than suffering.

Harlem’s Living Room of Black Art

If NMAAHC is a national altar, the Studio Museum in Harlem is a neighborhood living room. Founded in 1968 in a rented loft on Fifth Avenue, the museum was born of a simple conviction: that Harlem—the spiritual capital of Black America—deserved a museum that reflected its people. A group of artists, activists, philanthropists and residents envisioned an institution that would “pivot the artistic canon” and “make space for artists in Harlem.”

From the beginning, the Studio Museum was less concerned with neutral display than with participation. As its mission evolved, it defined itself as “the nexus for artists of African descent locally, nationally, and internationally” and for art influenced by Black culture. It became a site, in its own words, for “the dynamic exchange of ideas about art and society.”

For decades, its artist-in-residence program quietly reshaped contemporary art, nurturing figures who would later become fixtures in major museums and biennials. To walk through its galleries was to feel, often, as if you were seeing the canon being rewritten in real time.

Then, in 2018, the museum closed its longtime 125th Street building to make way for a new, purpose-built home. The hiatus stretched from months to years, slowed by the pandemic and construction delays. Harlem’s cultural landscape shifted around the empty lot: new condos climbed upward, beloved small businesses shuttered.

This fall, the Studio Museum reopened in a $160 million, 82,000-square-foot building designed by Adjaye Associates with Cooper Robertson. The seven-story structure nearly doubles its exhibition and programming space and features a soaring terrazzo-clad staircase that nods to Harlem’s stoops and church interiors.

Inside, the inaugural exhibition, “From Now: A Collection in Context,” draws from more than 9,000 works accumulated over half a century. It places early champions like Roy DeCarava and Faith Ringgold alongside contemporary stars such as Kehinde Wiley and Mickalene Thomas, tracing a lineage of Black visual imagination that once struggled to find wall space in mainstream museums.

For the museum’s director, Thelma Golden, the new building is less a destination than a tool. She has described the institution’s mission—to champion artists of African descent and their practices—as “as urgent today as it ever was,” now amplified by architecture that invites Harlem in.

On reopening weekend, that invitation is palpable. On the ground floor, a group of local teenagers—with lanyards identifying them as participants in a youth program—cluster in front of a monumental painting, trading observations and jokes. In an upstairs gallery, an older couple moves slowly from photograph to photograph, occasionally leaning in close to read wall labels. A docent guides a small group through an installation that reimagines Harlem as both real place and mythic symbol.

For some visitors, the museum functions as an extended classroom. For others, it is sanctuary. For emerging artists of African descent, it can be something more: proof that their work belongs not only in commercial galleries or online feeds, but in a museum that takes their experiments seriously.

Galleries as Economic and Cultural Engines

Not every Black-centric space has the visibility—or public funding—of NMAAHC or the Studio Museum. Across the United States and beyond, Black-owned galleries are quietly reshaping the art market, advocating for artists who might otherwise struggle to gain footholds in a field still dominated by white institutions and collectors.

In recent years, platforms such as Artsy and independent cultural outlets have highlighted a new generation of Black-owned galleries—Umoja, Greenhouse, Akoje, Arte de Gema, Jëndalma, Rele, Skoto, Sakhile & Me and others—operating from Lagos to Los Angeles, New York to Frankfurt.

Their founders are often part dealer, part community organizer. They host artist talks and workshops, connect young collectors to emerging talent, and insist on fairer representation and compensation for their artists. Many operate hybrid models—physical spaces paired with robust online programs—to bridge local communities and global markets.

For Black artists, the stakes are material as well as symbolic. The ability to show work in a gallery that understands the context of their practice can mean more stable careers and greater control over how their images are circulated and interpreted. For Black communities, these galleries create economic ecosystems: they employ staff, attract visitors, and support networks of framers, printers, caterers and designers.

They also complicate a long-standing tension in Black cultural life: the desire to make art that speaks honestly to Black experience, and the pressures of a market that sometimes fetishizes trauma or demands “political” work from Black artists while allowing white peers to remain abstract, apolitical, or whimsical.

Black-owned galleries, by virtue of who runs them and whom they serve, can create different terms of engagement. They are more likely to see, say, a vibrant portrait of everyday Black joy not as a deviation from “serious” work about injustice, but as a necessary complement to it.

Community Museums and the Work of Everyday Memory

Beyond the marquee institutions, a constellation of smaller African American museums stretches from Baltimore to Birmingham, from Kansas City to Los Angeles. Some are housed in former schoolhouses or churches; others occupy new or renovated buildings. Many are run on shoestring budgets, dependent on local donors, volunteers and modest grants.

These institutions, as the Urban Institute has noted, help “restore public memory” not in the abstract but at the neighborhood level. They chronicle local freedom struggles, document Black unions and social clubs, and preserve the histories of Black teachers, nurses, barbers and midwives whose names rarely appear in textbooks. They host school field trips, oral history projects, film nights and community forums.

In cities like Cincinnati, organizations have compiled guides to African American museums nationwide, framing them as essential stops on a “journey through history” that includes both well-known sites and lesser-known institutions such as Black wax museums and regional Black history museums.

For visitors, the impact can be intimate. A Black veteran seeing his regiment honored on a wall of photographs. A teenage girl recognizing her great-grandmother in a digitized church program. A recent immigrant from Africa encountering the story of the Middle Passage and chattel slavery in America, then seeing contemporary Black artists reimagining that history on canvas.

The value of these spaces cannot always be measured in attendance numbers or economic impact. It lies, instead, in the slow work of reshaping how a community understands itself—what it chooses to remember, whom it chooses to honor, how it teaches its children to navigate a world that still struggles to reckon with its racial past.

Museums in an Age of Backlash

The rise of Black-centric museums and galleries has coincided with a new wave of political pushback against teaching about race, slavery and systemic inequality. In recent years, school boards and state legislatures have sought to restrict how educators discuss racism. Some politicians have framed efforts to foreground Black history as divisive or “un-American.”

In that climate, African American museums have become targets as well as refuges. Their exhibitions and public programs can be dismissed by critics as “identity politics” or accused of rewriting history, even as they draw from decades of scholarship and primary sources long ignored by mainstream narratives.

Yet this backlash only underscores what many museum leaders have argued for years: that institutions are not neutral. To pretend otherwise is itself a political choice, one that often upholds existing power structures.

By contrast, Black-centric institutions are explicit about their commitments. They aim to correct omissions, amplify marginalized voices and present history from the vantage point of those who have lived it. They are not simply places where artifacts are stored; they are spaces where competing versions of the past are contested, negotiated and, sometimes, reconciled.

“African American museums preserve our history and share our stories,” one commentator wrote in 2020, noting that they emerged as “cornerstones of the Black Power movement” and remain vital “in the midst of racial unrest.”

At a moment when public debates over monuments, curricula and diversity initiatives can feel abstract or rancorous, these museums and galleries offer something more concrete: rooms full of objects and images that make denial harder.

The Quiet Radicalism of Being Seen

Back in Washington, the grandmother and her grandson move on from the shackles to an exhibit that reconstructs a slave cabin, then to galleries filled with portraits of Black activists, scientists, musicians and athletes. In one, a larger-than-life image of Serena Williams mid-serve; in another, a photograph of a Black woman in a lab coat, her name and achievements spelled out beneath the frame.

The boy lingers in front of the scientist’s portrait. “I didn’t know there were so many,” he says quietly. He doesn’t sound angry so much as startled, as if someone has just opened a door onto a room he didn’t know existed.

That moment—of recognition, surprise, possibility—is one of the subtler rewards of Black-centric museums and galleries. They do not only tell stories about pain and survival. They stage encounters with joy, innovation, beauty and ordinary Black life, allowing visitors to imagine futures beyond the constraints of the present.

For Black visitors, the effect can be affirming: the realization that their individual lives are part of a longer, collective story. For non-Black visitors, it can be destabilizing in productive ways: an invitation to see American history not as a single, seamless narrative but as a tapestry woven from many threads, some of them frayed or deliberately cut.

The economic value of these institutions is considerable. They draw tourists, support jobs, and contribute to local development. But their deeper value lies elsewhere—in the emotional and intellectual labor they perform on behalf of a country still learning how to tell the truth about itself.

Black-centric museums and galleries are, at their core, acts of faith: faith that objects can speak, that stories can heal, that seeing one’s ancestors honored on a museum wall might change how a young person moves through the world. They insist that Black people have always been, and will continue to be, central to the narrative of this country.

In an era of contested facts and curated feeds, stepping into these institutions can feel almost radical. Not because they offer easy answers, but because they offer something rarer: the chance to sit with complexity, to feel both grief and pride, to recognize the beauty and brutality braided through the Black American experience.

The grandmother and her grandson exit through the museum’s glass doors, back into the bright D.C. afternoon. They are, for a moment, silent. Then he turns to her.

“We gotta bring Mom next time,” he says.

It is as good a measure of value as any museum could ask for: the desire, after confronting the hardest parts of history, to return—and to bring more people with you.