No products in the cart.

KOLUMN Magazine

Wearing

Black

History

Black American entrepreneurs are turning streetwear into a moving archive—mapping Black Wall Streets and freedom towns onto premium hoodies and jackets that ask, quietly, who gets to own the future built on their past.

By KOLUMN Magazine

On a chilly November afternoon across most of the country, the hoodie does something a history book can’t.

It’s heavy in the hands—dense cotton, brushed soft lining, the kind of garment that sits on your shoulders with intention. For the founder of the Black-owned brand Tribe:Stitch, the hoodie is not just functional, its design is also a reminder of Black American communities that once fully represented to definitions of thriving, resilience and success.

Greenwood., Mound Bayou, Allensworth, Hayti District and select community names are boldly printed on each hoodie, a roll call of what the brand highlights as “Black Excellence.”

There are a hundred reasons shoppers might consider purchasing from Black-owned brands like Tribe:Stitch and other apparel companies. Stitched into the decision is often a set of calculations that have become increasingly common for Black shoppers: Who made this? What story is it telling? And whose future does my money help build?

Tribe:Stitch defines itself as being “committed to uplifting historic and present-day communities,” offering premium, heavy-weight outerwear that maps itself across the country’s Black business districts and freedom towns. Its launch this season places it inside a growing ecosystem of Black American entrepreneurs who are using clothing not just to dress bodies, but to archive memory, redirect dollars, and argue—quietly but insistently—that Black history belongs in the everyday: on sidewalks, in coffee lines, on the backs of people riding the bus.

In their hands, a hoodie is rarely just a hoodie. It’s evidence. It’s curriculum. It’s a small, soft protest you can throw in the wash.

Wearing the archive

The idea that Black Americans might use fashion as a tool for self-definition is hardly new. Tailored suits and Sunday dresses have long been central to what scholars call “respectability politics,” an attempt to counter racist caricatures with deliberate elegance. A new exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Superfine: Tailoring Black Style,” traces this history from Frederick Douglass’s carefully chosen coats to contemporary designers like Virgil Abloh and Grace Wales Bonner, framing Black menswear as both self-expression and survival strategy.

But in the last decade, something more specific has taken hold: a wave of Black-owned apparel brands that don’t just reflect Black culture and history but explicitly teach it.

Some of these companies are small-batch streetwear operations; others are ambitious labels flirting with luxury. In Philadelphia, Blk Ivy Thrift, founded by educator and designer Dr. Kimberly McGlonn, evolved from a storefront into a traveling exhibition that pairs vintage clothing with Civil Rights–era artifacts and audio recordings. Visitors might see a 1960s Lee denim jacket displayed alongside a quote from Martin Luther King Jr., or a rack of collegiate blazers curated to evoke the Black students who integrated Southern campuses. McGlonn describes her work as “history woven into fabric,” a form of cultural preservation in a moment when diversity initiatives and even African American studies courses are under attack.

On larger stages, designers like Grace Wales Bonner have used runways to stage their own archival projects. Her London-based label, celebrated in fashion media, grounds its tailored silhouettes in rigorous research on Black diasporic aesthetics and Caribbean heritage. In New York, Telfar Clemens has turned his namesake brand into a case study in community-led luxury, marking its 20th anniversary this year with a street runway show that doubled as a block party. The now-iconic Telfar shopping bag, with its unmissable logo, has become as much a symbol of queer Black creativity as it is an accessory.

At the grassroots level, a constellation of brands explicitly invoke Black Wall Street—the nickname for Greenwood, Tulsa’s early-20th-century Black business district—to honor what was and what was taken. The Blackest Co., a Black-owned design company, sells “Never Forget” hoodies and T-shirts memorializing the 1921 massacre. Tulsa’s own Black Wall Street Tees, operating in the historic district, offers hoodies printed with “1921” and “Greenwood” in bold lettering, doubling as both souvenir stand and informal interpretive center for visitors who wander in from the nearby memorial. Greenwood Ave, another brand, sells sleek Black Wall Street bomber jackets with the tagline “merch designed to honor the past and inspire the future of dreamers and doers.”

To wear one of these garments is to place yourself, quite literally, inside a narrative about Black enterprise and catastrophe. It is also, increasingly, to participate in an economic strategy.

The long arc of “buy Black”

A century ago, the phrase “Black Wall Street” described a place: a 35-block neighborhood of Black-owned businesses, churches, hotels, and homes in Tulsa, Oklahoma. The community flourished in the shadow of Jim Crow until May 31 and June 1, 1921, when white mobs—some deputized by local officials—launched a coordinated assault, burning Greenwood to the ground and killing as many as 300 Black residents. A new Justice Department report released this year describes the massacre as a “military-style attack” that involved both private citizens and public authorities.

What followed was a near-total erasure: of businesses, of property records, of lives. Survivors never received compensation. The district was reduced to a fraction of its former footprint, its story largely absent from mainstream textbooks until the massacre’s centennial forced a broader reckoning.

In that context, the proliferation of Black Wall Street hoodies and caps is complicated. For some critics, the merch risks trivializing trauma, turning massacre into aesthetic. For others, it’s a pragmatic way to ensure the name Greenwood stays visible—in airports, grocery store aisles, Zoom calls—long after official commemorations fade.

Underneath those debates lies a much older conversation about how Black Americans use their dollars.

In the 1930s, Black communities in cities like Chicago and Washington launched “Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work” boycotts, leveraging consumer power to demand jobs at white-owned businesses that depended heavily on Black customers. In the 1960s, civil-rights organizers paired sit-ins and marches with strategic boycotts. By the 2010s, hashtags like #BuyBlack, We Buy Black, and Bank Black urged consumers to redirect everyday spending toward Black-owned businesses and financial institutions.

As journalist accounts of that movement note, the bank customer—ordinary people moving checking accounts from national chains to Black-owned banks—became both symbol and actor. The interest rates were rarely better; the apps were sometimes clunkier. But seeing local loan programs or small-business success stories in the news allowed depositors to imagine their balance transmuted into someone else’s storefront.

Today’s “buy Black” moment, invigorated by the 2020 racial justice uprisings and then tempered by a backlash against corporate diversity programs, is less about scarcity of options than about visibility. Black buying power is expected to surpass $2 trillion by the middle of this decade, yet Black-owned firms still represent only a sliver of employer businesses and business revenue in the United States. The gap is not just about who owns the companies, but about which brands consumers can easily find.

That visibility problem has spawned its own infrastructure. There are directories like BuyBlack.org and certification programs such as ByBlack, created by the U.S. Black Chambers. And there are curated guides like BRANDED, BLACKNESS, a digital platform designed specifically to help shoppers locate Black-owned beauty and wellness brands without sacrificing aesthetics or convenience.

Scroll through BRANDED, BLACKNESS on a phone and you encounter a highly produced grid of glossy product shots and storytelling captions—an attempt to make the act of seeking out Black-owned brands feel like a natural extension of Instagram-era shopping rather than extra homework.

Somewhere in those feeds, tucked among hair oils and skincare serums, an ad for Tribe:Stitch appears.

Mapping Black prosperity, one hoodie at a time

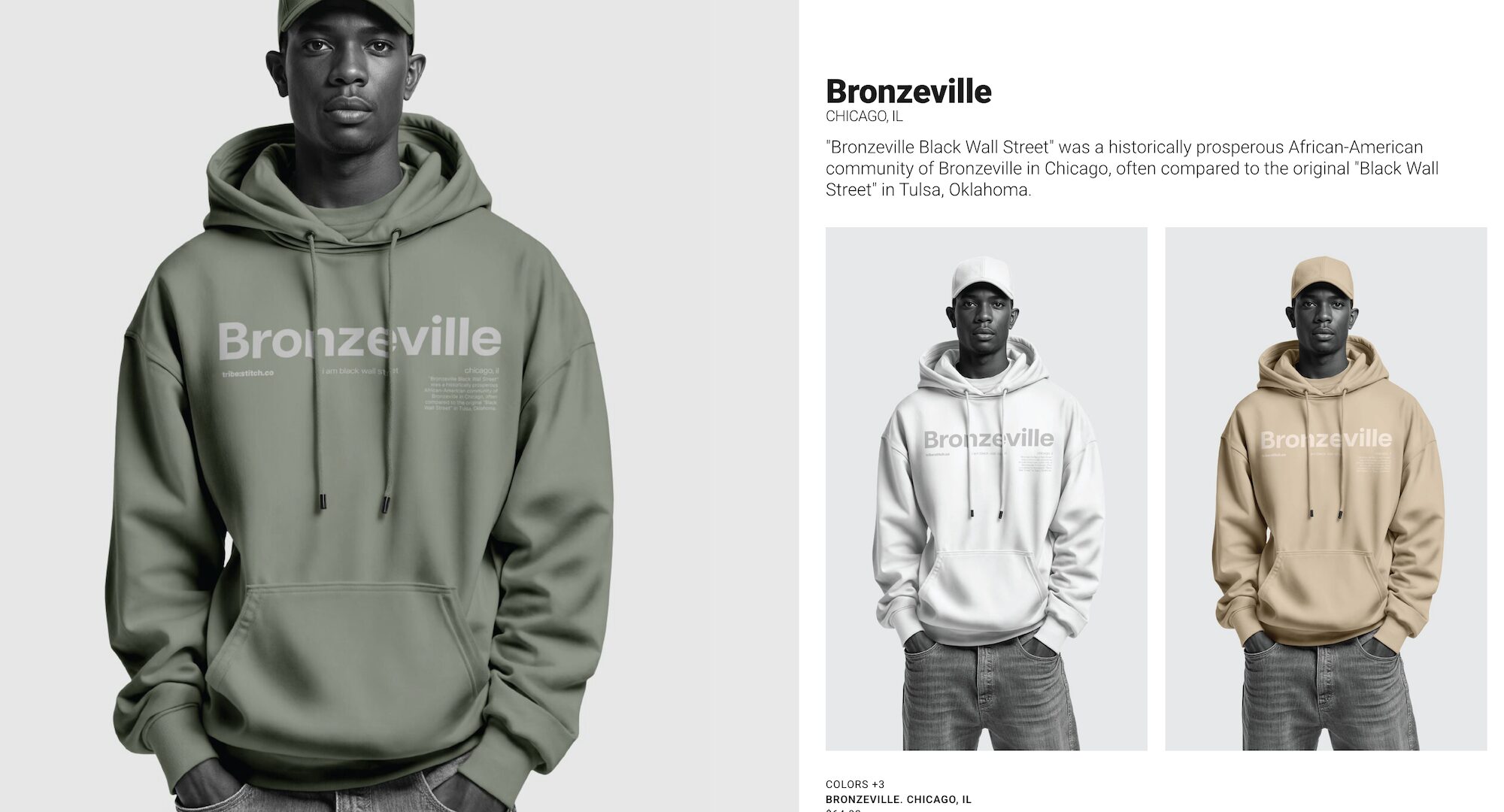

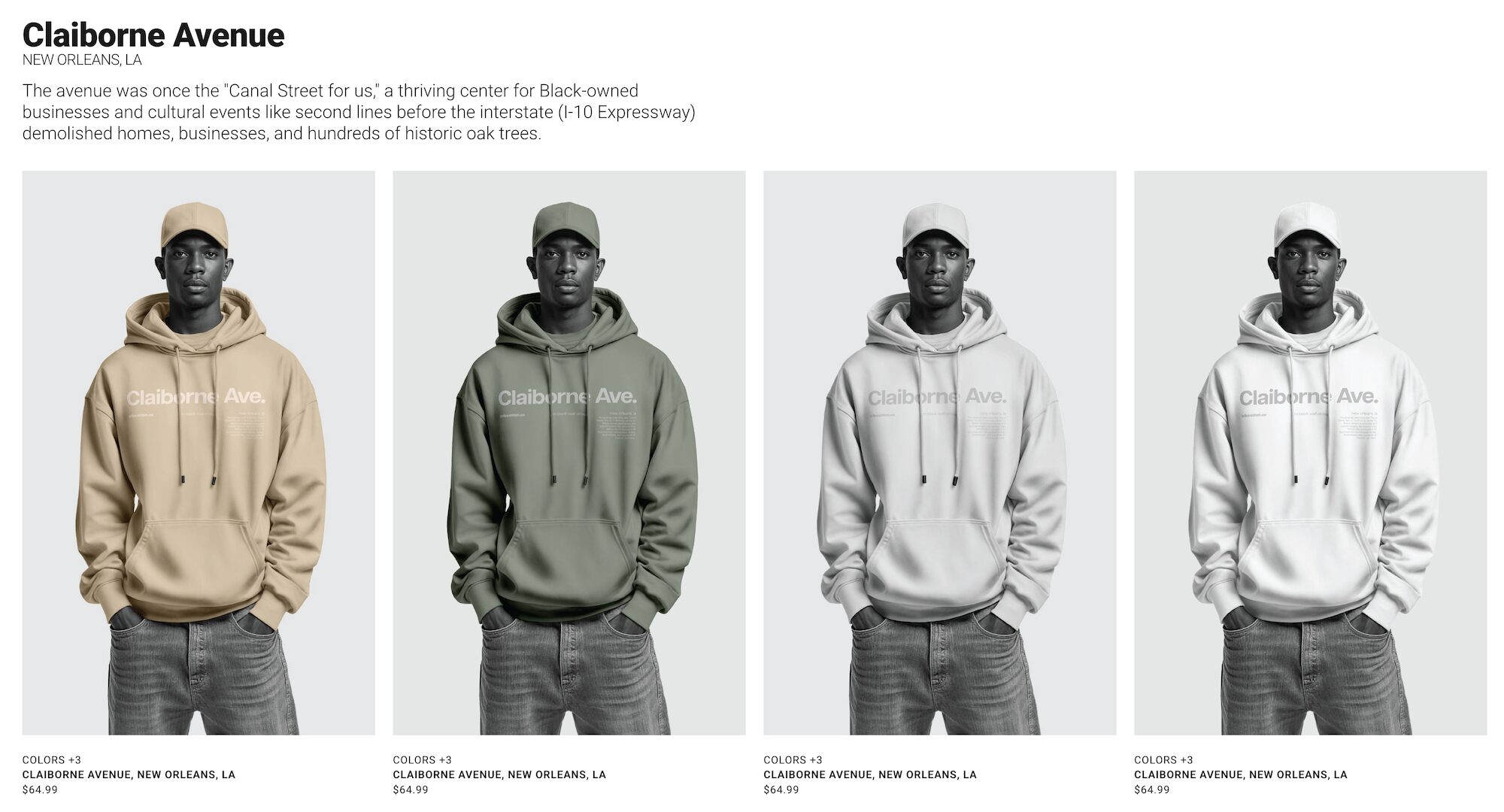

Tribe:Stitch doesn’t look like a start-up scrambling to go viral. The website, built around a muted palette and archival-style photography, opens with a simple announcement—launching on Black Friday 2025—and a sign-up box for updates. Scroll, and the site becomes a map: Allensworth, California; Blackdom, New Mexico; Bronzeville, Chicago; Claiborne Avenue in New Orleans; Eatonville, Florida; Farish Street in Jackson; Fourth Avenue in Birmingham; Freedmen’s Town in Houston; Greenwood in Tulsa; Hayti and Parrish Street in Durham; Jackson Ward in Richmond; Mound Bayou in Mississippi; Nicodemus, Kansas; Seneca Village in New York; Sweet Auburn in Atlanta.

Each place gets a short, textbook-clear description:

Allensworth, founded in 1908 by Colonel Allen Allensworth and fellow settlers, described as California’s first all-Black township.

Eatonville, incorporated in 1887 and widely recognized as the first self-governing all-Black municipality in the U.S.

Seneca Village, the mid-19th-century Black landowning community in Manhattan that was destroyed to create Central Park.

The garments themselves are understated—clean fonts, minimal graphics, sometimes nothing more than the community name and state placed across the chest. The drama comes from the context.

In promotional copy that has begun appearing as sponsored content alongside longform journalism on Black economics and culture, the brand explains its thesis plainly: premium, heavy-weight hoodies and jackets that are “far beyond your standard” outerwear, designed to honor historic and present-day Black communities.

If many Black-owned apparel brands trade in broad statements—“Black Excellence,” “Melanin Poppin’,” “Unapologetically Black”— Tribe:Stitch makes a narrower bet: that customers will pay luxury-level prices for garments that function almost like wearable history books.

The founder, Willoughby Avenue, a Black-owned social brand publisher & agency, are less interested in becoming personalities than in curating a canon. Where some labels lean into the designer-as-celebrity model, Tribe:Stitch centers the towns.

That decision shifts attention from the lone genius to the collective work of communities that built businesses, schools, mutual aid societies, and churches under the constant threat of violence or displacement. It also invites wearers into a kind of paced research. Someone who buys a Mound Bayou hoodie might later discover that the Mississippi town, founded in 1887 by formerly enslaved people, became a symbol of Black self-governance and was once visited by both Booker T. Washington and Teddy Roosevelt.

Similarly, a Claiborne Avenue hoodie or jacket may send a wearer down a rabbit hole on how an interstate highway project in New Orleans demolished a thriving Black business corridor and hundreds of oak trees, reshaping a neighborhood in ways that residents still contest.

The brand’s timing is not incidental. Tribe:Stitch arrives in a moment when school boards in several states are restricting how teachers can describe slavery, segregation, and systemic racism in classrooms. In that climate, the act of wearing a hoodie that quietly insists, Seneca Village existed; Sweet Auburn was once called “the richest Negro street in the world”; Greenwood was burned is a kind of counter-syllabus.

Rebuilding the supply chain, not just the story

If mapping historic communities is one axis of this new wave of Black-owned apparel, another runs through the supply chain itself.

In 2018, Air Force veteran Tameka Peoples launched Seed2Shirt after realizing that, while she could buy T-shirts from Black-owned print shops, the garments themselves were rarely grown or sewn by Black people. She imagined something different: cotton farmed by Black farmers, processed and cut in facilities across the African continent, then printed and sold by Black-owned companies.

Seed2Shirt, as profiled by Word In Black, describes itself as the first Black-woman-owned, vertically integrated apparel manufacturing and print-on-demand company in the United States. Its production process sources organic cotton from West African farmers—most of them women—then moves fabric through Ugandan mills and Kenyan cut-and-sew factories before garments ship out to U.S. clients. Profits help fund a Farmer Enrichment Program that has reached hundreds of thousands of cotton farmers with training on soil health and business skills.

For Peoples, the point is not just to sell shirts with liberatory slogans, but to build an alternative system where Black communities share in the value created at every stage. “Everything has a cause, and everything has an impact,” she told a reporter. “How you consider that and how you consider people and the impact on the environment should really be baked into your pattern of life.”

Seed2Shirt’s story underscores a tension that runs through much of the Black-owned fashion space: narrative versus material conditions. Clothing that celebrates Black history can be powerful, but without changes in who controls land, factories, and capital, the industry’s underlying hierarchies remain stubbornly intact.

Tribe:Stitch’s manufacturing footprint is evolving; its messaging leans more heavily on storytelling, premium fabric, and small-batch quality than on radical reinvention of the supply chain. In that sense, it occupies a middle ground familiar to many emerging Black brands: navigating an industry whose infrastructure is still largely controlled by non-Black firms, while trying to carve out room for more equitable futures.

Fashion as classroom, fashion as mirror

At the Met, the “Superfine” exhibit invites visitors to linger over Frederick Douglass’s coat, André Leon Talley’s ecclesiastical cloaks, and contemporary suits by designers like Wales Bonner. Curator Monica L. Miller has described the show as a way to trace not just trends, but the “commanding presence” of Black male style—the way it has both accommodated and subverted the gaze of institutions that once excluded Black bodies entirely.

On a different scale, Blk Ivy Thrift’s installations re-create 1970s living rooms and Civil Rights–era campuses with clothing and ephemera, turning shopping into a kind of embodied seminar. Visitors wander through curated vignettes, hearing the voices of Angela Davis or James Baldwin over speakers while fingering the seams of vintage knitwear. For McGlonn, the project is an explicit response to what she sees as the erosion of democracy and attacks on curricula that center Black life. “Through fashion, through storytelling,” she told Vogue, “we fight for cultural preservation.”

Tribe:Stitch’s classroom is more diffuse. Its garments will appear in group chats and office Zoom tiles, at HBCU homecomings and independent retailers. They may be worn by people who know every footnote of Eatonville’s history and by those who just liked the colorway. But the brand is betting that repetition matters—that the more often someone sees the word Nicodemus on a hoodie, the less likely it is that the Kansas town, founded by formerly enslaved people in 1877, will slip entirely from public memory.

For customers, the experience of shopping these brands often feels like a negotiation between aesthetics and alignment. As one Word In Black piece on holiday shopping framed it, the question is no longer whether to buy gifts, but where to buy them: from big-box stores with uncertain commitments to Black communities, or from Black-owned businesses whose marketing makes those commitments explicit.

In practice, the choices are rarely pure. A person might move their account to a Black-owned bank but still buy groceries at a national chain; they might splurge on a Tribe:Stitch hoodie while wearing mass-market jeans. And even the most beautifully curated directories cannot fix the structural forces—capital access, discriminatory lending, zoning decisions—that make it difficult for Black-owned firms to scale.