KOLUMN Magazine

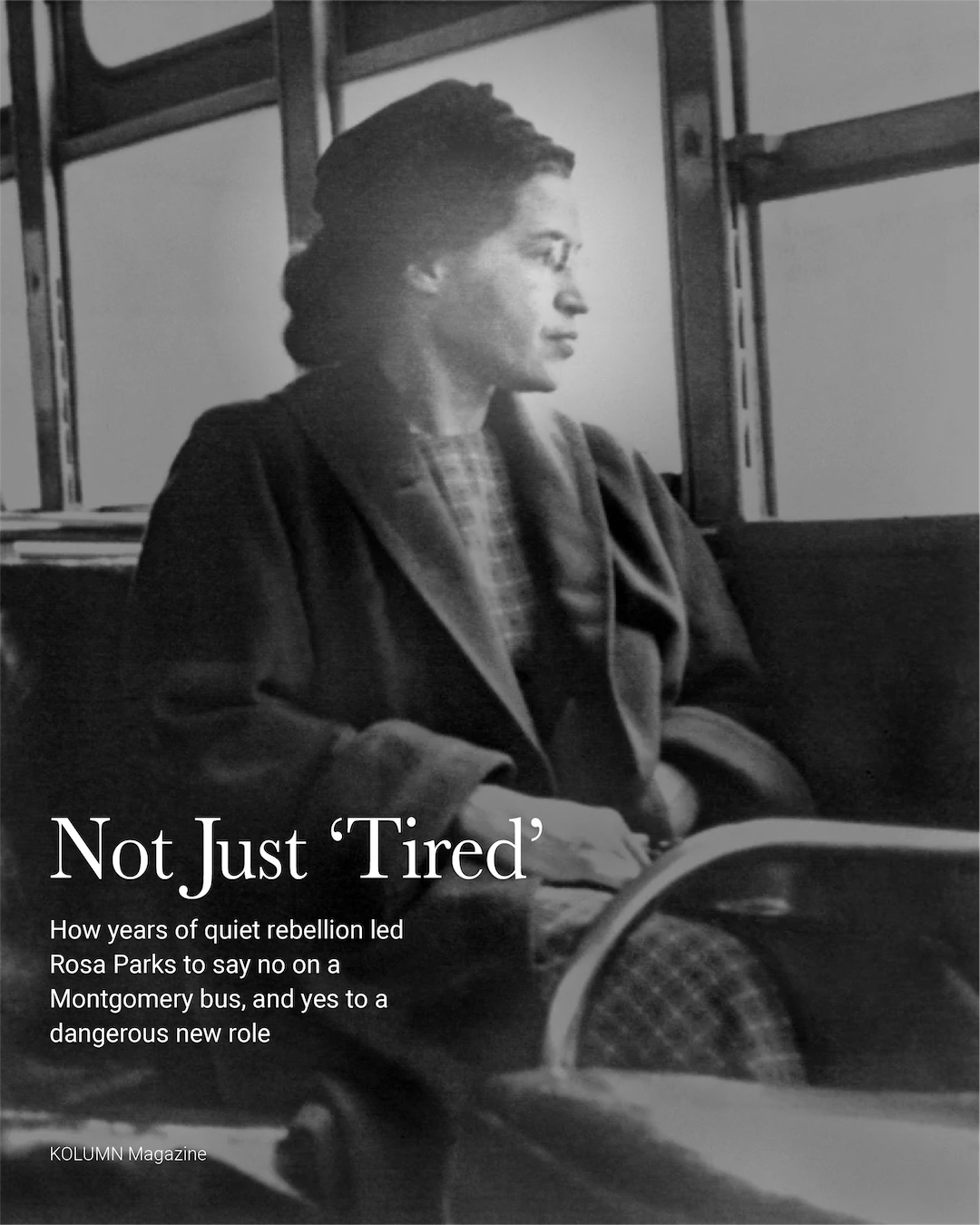

rosa

parks:

Not Just

TIRED

How years of quiet rebellion led Rosa Parks to say no on a Montgomery bus, and yes to a dangerous new role

By KOLUMN Magazine

In the fading light of a Thursday in Montgomery, Alabama, the day did not look like history.

It looked like rush hour.

Downtown, department-store windows were just beginning to glow against the early December dark. Workers in starched uniforms and threadbare overcoats streamed off sidewalks toward the bus stops, tired from standing on concrete floors, from minding white children, from cooking meals they never tasted. On Court Square, where the streetcars had once turned and slave auctions had been held a century earlier, a 42-year-old seamstress named Rosa Parks stepped off the curb, holding a purse and a paper shopping bag.

Parks had clocked out from her job at Montgomery Fair department store a little after 5 p.m., after a day operating a heavy steam press in the tailoring department. The first Cleveland Avenue bus she approached was already jammed. Parks, who suffered from chronic bursitis that left her shoulders aching, decided not to wedge herself into the crush. Instead she crossed to Lee’s Cut-Rate Drug, bought a few small items, and waited for a less crowded bus.

By the time she boarded bus No. 2857 around 6 p.m., the day behind her was, in nearly every respect, ordinary. It was what happened over the next several hours—and how a city responded before the sun rose again—that would turn December 1, 1955, into one of the hinge dates of American history.

What we know of Rosa Parks’ full day—those quiet hours before the flashbulbs and the fingerprint ink—comes to us in fragments: arrest records and police reports, later interviews and memoirs, the recollections of colleagues and neighbors. The legend that grew around her has often sanded those fragments into a single, simple story: a tired woman who had simply had enough. The reality was more complicated—and more radical.

Morning in Cleveland Courts

The calendar in the Parks household that morning read “Thursday.” Nothing about the date, circled in red or marked with stars, set it apart.

Rosa and her husband, Raymond, lived with her mother in a modest unit—No. 634—in the Cleveland Courts public housing complex on Cleveland Avenue, a working-class Black neighborhood west of downtown. The family had been there since the early 1940s, never able to afford a home of their own. The apartment would later be listed on the National Register of Historic Places, but in 1955, it was simply a place where the rent had to be paid and the meals cooked, where the laundry piled up like it did in every other working family’s home.

By then, Parks’ public life was layered on top of the domestic rhythms of this place. For more than a decade, she had served as secretary of the Montgomery branch of the NAACP, taking minutes in meetings, filing complaints, and—far more dangerously—investigating cases of racist violence, including the 1944 gang rape of Recy Taylor, a Black sharecropper kidnapped and assaulted by white men. She had traveled to the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee the previous summer to attend workshops on school desegregation and organizing, a kind of political boot camp for Southern activists where she lived, briefly, in an integrated community she later described as a revelation.

None of that would have been visible to a stranger watching her on the morning of December 1. They might have seen only what the later “master narrative” preferred: a quiet, churchgoing seamstress in a sensible coat and hat.

Yet that morning, as on so many others, Parks would have moved through a world thick with reminders of why she organized at night and on weekends. Jim Crow signs divided lunch counters and waiting rooms. Black bus riders, who made up roughly three-quarters of Montgomery’s passengers, still had to enter through the front door to pay, then get off and re-enter through the back—a ritual humiliation that gave drivers enormous discretionary power over Black riders’ bodies and time.

Twelve years earlier, on this same Cleveland Avenue line, a bus driver named James F. Blake had ordered Rosa Parks off his bus when she refused to re-enter through the back door after paying her fare. She had stepped off into the Montgomery heat that day rather than submit.

On December 1, 1955, she left Cleveland Courts once again to catch the bus to her downtown job. The workday ahead was not a protest. It was the price of survival.

A Long Day’s Work

Montgomery Fair was the kind of department store that advertised itself as a symbol of modern Southern prosperity. Its gleaming counters and Christmas displays depended on a Black labor force that moved mostly through back entrances and service corridors. Parks worked there as a seamstress and tailor’s assistant, hemming garments and pressing clothes for customers who might never learn her name.

Accounts differ on the exact mood of her day—there are no surviving time sheets that note irritation or joy—but the work itself was repetitive and physically taxing. A former colleague recalled the hours on her feet at the steam press, the heat and humidity of the workroom. In her own autobiography, Parks would later insist that she was no more tired than usual when her shift ended: “People always say that I didn’t give up my seat because I was tired, but that isn’t true,” she wrote. “I was not tired physically, or no more tired than I usually was at the end of a working day. … No, the only tired I was, was tired of giving in.”

The distinction matters. It shifts the story from a tale of individual exhaustion to one of deliberate political choice.

What is clear is that, over lunch breaks and in quiet moments that fall, Parks’ world had been filled with news of Black suffering and fragile attempts at justice. She had followed the case of Emmett Till, the 14-year-old boy lynched in Mississippi that August, and attended a local meeting about his murder. She had grown frustrated with what she described as “vague promises” and “run-around” from city officials about improving bus service, finally refusing to attend yet another fruitless meeting.

The movement was looking for a test case; the Women’s Political Council, led by Jo Ann Robinson, had long been discussing a bus boycott. Parks knew all this. She knew, too, that Black women—domestic workers, clerks, schoolteachers—were the ones who bore the brunt of bus segregation.

What she did not do, historians emphasize, was step onto the Cleveland Avenue bus that evening as part of a scripted plan. Jeanne Theoharis, one of Parks’ leading biographers, puts it this way: “She prepared herself with an assured readiness, which she could rely on when an opportunity occurred.”

Court Square, 5:30 p.m.

Shortly after 5 p.m., Parks clocked out. On a cool, damp evening, she walked west along Montgomery Street toward Court Square, the city’s central transfer point.

The first Cleveland Avenue bus she approached—its route number familiar from years of commuting back toward Cleveland Courts—was already crowded, with Black passengers standing in the aisle. She opted to wait, stepping into Lee’s Cut-Rate Drug. She bought a few small items—Christmas presents, perhaps, or necessities for the apartment. The receipt, if it existed, is long gone, but the stop itself is part of the reconstructed timeline drawn from later reporting and scholarship.

When she emerged, another Cleveland Avenue bus was pulling up: No. 2857, driven, though she did not immediately notice, by James F. Blake—the same driver who had humiliated her twelve years earlier.

She boarded through the front entrance, paid her fare, and walked back to the middle section, where Black passengers were permitted to sit until the white section filled. She took an aisle seat in the first row of the “colored” section, beside a Black man and across from two Black women.

Outside, the bus rolled past the Empire Theater and other downtown landmarks. All the white-designated seats filled. At the third stop, a small group of white passengers climbed aboard. One white man remained standing.

Blake turned around.

“Move y’all, I want those seats,” he shouted, according to several later accounts.

Under Montgomery’s ordinance, Black riders were technically not required to give up their seats if they were already in the “colored” section. But custom—and the white supremacist logic that governed every corner of the city—gave drivers broad authority to re-draw the line at will.

The three other Black passengers in Parks’ row stood up and moved. She slid closer to the window but stayed seated.

Blake asked if she was going to stand. She answered, calmly, that she was not. When he threatened to have her arrested, she replied: “You may do that.”

“Why Do You Push Us Around?”

Blake left the bus and called the police from a nearby phone. Officers F.B. Day and D.W. Mixon arrived within minutes.

Climbing the bus steps, they asked Parks why she hadn’t stood up. She later recalled her response in multiple interviews and writings: “I told them I didn’t think I should have to stand up.” As they prepared to arrest her—each taking one of her bags, escorting her off the bus—she asked a question that would echo through decades of retellings: “Why do you push us around?”

The official police report, later displayed by the National Archives alongside a diagram of the bus, recorded the incident in clipped, bureaucratic prose. Parks, it claimed, had been “sitting in the white section of the bus” and had “refused to move back.” The diagram shows otherwise: she was in the first row of the Black section.

From the bus, officers took her to Montgomery City Hall to be booked on a charge of violating the city’s segregation ordinance. Then she was moved to the city jail, fingerprinted, and photographed.

Only after repeated requests was she allowed to make a phone call. She rang home, where her mother, Leona, answered. Leona reached out to E.D. Nixon, the former head of the local NAACP chapter and a Pullman porter with deep ties in the Black community.

Parks, sitting in a cell in her work clothes and hat, now became something she had long imagined and dreaded: a legal test case.

“Why Do You Push Us Around?”

Blake left the bus and called the police from a nearby phone. Officers F.B. Day and D.W. Mixon arrived within minutes.

Climbing the bus steps, they asked Parks why she hadn’t stood up. She later recalled her response in multiple interviews and writings: “I told them I didn’t think I should have to stand up.” As they prepared to arrest her—each taking one of her bags, escorting her off the bus—she asked a question that would echo through decades of retellings: “Why do you push us around?”

The official police report, later displayed by the National Archives alongside a diagram of the bus, recorded the incident in clipped, bureaucratic prose. Parks, it claimed, had been “sitting in the white section of the bus” and had “refused to move back.” The diagram shows otherwise: she was in the first row of the Black section.

From the bus, officers took her to Montgomery City Hall to be booked on a charge of violating the city’s segregation ordinance. Then she was moved to the city jail, fingerprinted, and photographed.

Only after repeated requests was she allowed to make a phone call. She rang home, where her mother, Leona, answered. Leona reached out to E.D. Nixon, the former head of the local NAACP chapter and a Pullman porter with deep ties in the Black community.

Parks, sitting in a cell in her work clothes and hat, now became something she had long imagined and dreaded: a legal test case.

The Night’s Other Phone Calls

What happened in the hours after Parks’ arrest is sometimes treated as background to the iconic photograph of her later sitting, serene and composed, on a desegregated bus. But those hours were frantic, improvisational—and decisive.

When Nixon got word that Rosa Parks had been arrested, he understood immediately that the moment he and others had been preparing for might have arrived. He drove to the jail with his white friends and allies, attorney Clifford Durr and his wife, Virginia, to post bail.

The amount—$100—was steep for a working-class couple. The Durrs wrote the check. Parks was released into a cold, wet night, aware that she had crossed a line no one could uncross for her.

Later that evening, Nixon went to the Parks apartment at Cleveland Courts. There, over coffee at the kitchen table or in the small front room—accounts differ on the exact scene—he asked if she would be willing to let her case challenge the city’s segregation law. He reminded her of the risks: she could lose her job; they might be subjected to threats, violence, ostracism. Parks conferred with Raymond and her mother. She agreed.

Nixon, in turn, started making his own phone calls: to the rising young pastor of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, Martin Luther King Jr.; to his friend Ralph Abernathy; to other Black clergy and civic leaders. They agreed to meet the next day to consider a protest.

Meanwhile, attorney Fred Gray called Jo Ann Robinson, the English professor at Alabama State College who headed the Women’s Political Council. For years, Robinson and other Black women had been cataloguing riders’ complaints about bus segregation, drafting petitions, and warning city officials that “a city-wide boycott of buses could be called at any time.” The warning had been easy for white leaders to dismiss when it was hypothetical.

Now Gray told her: Rosa Parks had been arrested. Her trial would be on Monday.

“I got on the phone and called all the officers of the three [WPC] chapters,” Robinson later wrote. “They said, ‘You have the plans, put them into operation.’”

The Mimeograph Night Shift

Late that night, while much of Montgomery slept, Robinson drove to the Alabama State campus. With the help of two students and John Cannon, chair of the business department, she commandeered a mimeograph machine and began churning out leaflets.

“Another Negro woman has been arrested and thrown in jail because she refused to get up out of her seat on the bus,” they read. “This has to be stopped. Negroes have rights, too, for if Negroes did not ride the buses, they could not operate.”

They called for a one-day boycott of Montgomery’s buses on Monday, December 5—the day of Parks’ trial.

By dawn, somewhere between 35,000 and 50,000 leaflets had been printed, cut, and bundled. Teachers slipped them into students’ hands; ministers tucked them into church bulletins; barbers left stacks on their counters. In a matter of hours, without text messages or social media, the city’s Black community had been alerted and mobilized.

In that sense, the night belonged as much to collective infrastructure as to a single arrest: to the women marshaling mimeograph ink and shoe leather, to the church phone trees, to the quiet conversations in kitchens and on street corners.

Back at Cleveland Courts, Rosa Parks tried to rest. The day’s events had left her, as she would later put it, “a little bit nervous and frightened” but also unexpectedly calm. “I had no idea that history was being made,” she wrote years later. “I was just tired of giving in.”

Outside, the buses kept running their evening routes, unaware that many of the Black riders whose fares sustained them were already planning to walk.

Monday and Beyond

The next Monday morning, in a steady rain, Montgomery’s Black residents stayed off the buses.

Domestic workers walked miles to white neighborhoods to cook and clean. Teachers and shop clerks formed ad hoc carpools. Those who absolutely had to ride wore their Sunday clothes and kept their heads high. At the courthouse, where Parks’ brief trial on the municipal charge took place, a crowd of nearly 500 Black residents gathered in support. She was found guilty and fined $10 plus court costs. Gray immediately announced an appeal.

That afternoon, ministers and community leaders met at Mount Zion A.M.E. Zion Church to discuss extending the protest. By evening, at Holt Street Baptist Church, a crowd estimated between 5,000 and 8,000 people overflowed the sanctuary and spilled into the street. They voted to continue the boycott and formally created the Montgomery Improvement Association, electing King as its president. Parks, seated quietly near the front, was introduced to thunderous applause.

What had begun with an ordinary bus ride and an extraordinary refusal became a 381-day mass action: carpools and walking lines, arrests and lawsuits, bombings and boycotts, ultimately culminating in the Supreme Court’s 1956 decision in Browder v. Gayle, which declared bus segregation unconstitutional.

For Parks herself, the personal cost was steep. Within weeks she was fired from Montgomery Fair; Raymond lost his job too. The family’s finances collapsed, and the stress took a toll on her health. In 1957, they left Montgomery for Detroit, where she continued to work, often without pay, for civil-rights causes for decades.

Unlearning the “Quiet Seamstress”

If we try to reconstruct Rosa Parks’ full day on December 1, 1955, the temptation is to turn it into a morality play: the humble heroine, the villainous driver, the miraculous chain of events that followed. The story we often teach children—of a lone, apolitical woman who simply “got tired” and sat down—strips away the most radical truth about her life: that what happened that evening was the product of long, patient, dangerous work.

Historians like Theoharis and Gary Younge have spent years challenging that comforting myth. Parks was not an accidental actor but a seasoned organizer whose moral courage had been forged in years of investigation, petitioning, and study. She had watched other Black women—Claudette Colvin, Aurelia Browder, Mary Louise Smith—be arrested for similar acts on Montgomery’s buses and then passed over by conservative leaders as test cases. She knew, as she boarded No. 2857, that she might one day face the same choice.

But the myth has its own power. The image of “a tired seamstress who just wanted to go home” suggests a democracy in which great political shifts can emerge spontaneously from private grievance, without the messy work of organizing. It is easier to honor a woman who sat down than one who kept standing up afterward—against police brutality, sexual violence, northern housing discrimination, and the war in Vietnam.

To follow Rosa Parks through the whole of December 1, 1955, is to see both versions: the ordinary and the insurgent, the quiet gesture and the long, loud echo.

In the morning, she left a public-housing apartment that held three generations and headed to a job that barely paid enough. At midday, she pressed seams in a department store whose white customers rarely imagined her as a political actor. In the late afternoon, she weighed whether to squeeze onto a crowded bus or wait in a drugstore. In the early evening, she refused to move.

And that night—while she sat at her kitchen table with her husband and mother, weighing the risks of becoming the face of a legal challenge; while Jo Ann Robinson and her students fanned hot mimeograph pages; while ministers answered late-night phone calls and agreed to a Monday meeting; while thousands of Black workers laid out their walking shoes for a long Monday march—a city quietly rearranged itself around what she had done.