KOLUMN Magazine

The

Afterlife

of Black Eden

Once the hottest Black resort in America, Idlewild drew everyone from Du Bois to Aretha. Now a small band of believers is trying to bring it back.

By KOLUMN Magazine

On a July night in the late 1950s, the line outside the Paradise Club snaked past the pines and down the dusty road toward Idlewild Lake. Women in taffeta skirts and pressed linen sandals picked their way along the sand. Men, their shoulders squared in summer-weight suits, passed flasks and gossip as they waited to get in before the band struck its first note.

Inside, the room glowed. White tablecloths, waiters weaving through with steaks and highballs, a low murmur of middle-class pleasure. Onstage, a young Jackie Wilson would soon fling himself into a split, or B.B. King would lean back into a solo that made the parquet floor tremble. For a few hours, this clearing in the Michigan woods—three hours northwest of Detroit—felt as grand as Harlem’s Apollo, as worldly as Paris.

This was Idlewild, Michigan: the resort town that became known across Black America as “Black Eden.”

Today, if you drive those same roads, the pines are still there, but the Paradise is long gone, reduced to memory and a historical marker. Some cottages sag behind stands of oak. Others have been lovingly repainted by retirees and dreamers who never quite gave up on the place. A Juneteenth festival brings food trucks and fashion shows to a small island named for Dr. Daniel Hale Williams, the pioneering Black surgeon who once summered here.

On most days, Idlewild feels quiet—almost improbably quiet for a town that once hosted an estimated 25,000 visitors each summer and supported some 300 Black-owned businesses. Yet if you listen—to the people who still come back year after year, to the old photographs and yellowed flyers, to the elders building parks and running small museums—you can still hear what drew generations here: the sound of Black people at ease.

A Resort Built on a Segregated Dream

Idlewild began, improbably, as a business opportunity spotted by four white couples in 1912. Erastus and Flora Branch and Adelbert and Isabelle Branch from the small town of White Cloud, Michigan, joined forces with Chicagoans Wilbur and Mayme Lemon and A.E. and Madolin Wright. They formed the Idlewild Resort Company and quietly purchased roughly 2,700 acres of woodland wrapped around five lakes.

The idea was simple and shrewd. Jim Crow laws and informal segregation meant that Black professionals—doctors, teachers, ministers, lawyers—could afford vacations but not access many of the resort towns that catered to white visitors. If you created a northern resort that explicitly welcomed Black vacationers, you could sell not only rooms but land itself.

So the partners went after their customers in the pages of the Black press. Ads appeared in the Chicago Defender and other regional papers, touting Idlewild as a hunter’s paradise with clean air, bright water, and the rare promise of both ownership and safety. Lots were 25 by 100 feet and, according to one development report, could be had for $35—six dollars down and one dollar a month afterward.

Salespeople fanned out from Detroit and Chicago, sometimes paid in land for every lot they sold. They organized train excursions to the new resort so prospective buyers could see it for themselves: a lakeside playground with the faint outlines of roads and cabins in the sand.

Black investors quickly followed. Among the early landowners and visitors were W.E.B. Du Bois, Madam C.J. Walker, novelist Charles Chesnutt and Dr. Daniel Hale Williams. Du Bois later wrote rapturously of Idlewild’s “golden air” and fellowship; his description helped cement the “Black Eden” nickname that would stick for generations.

But beyond the famous names, Idlewild attracted thousands of strivers whose stories rarely made it into the newspapers: Pullman porters who saved for a lot, beauty-school owners from Cleveland, teachers from Gary and Chicago, funeral-home directors and postal workers and small-business families who came north chasing the same promise that fueled the Great Migration—only this time, the promise was leisure.

Buying a Piece of Freedom

For many who bought into Idlewild, the first real thrill wasn’t the lake or the pine-scented air. It was the deed.

Land ownership, particularly in a rural setting, had often been violently denied to Black families—through discriminatory lending, targeted violence, and the quiet refusal of white sellers and real estate agents. In Idlewild, a Black dentist from Detroit and a Black grocer from Chicago could both walk into a sales office, pay their installments, and walk out knowing they would own a piece of ground where their grandchildren could build a cottage.

Idlewild’s lot owners organized quickly. The Idlewild Lot Owners Association grew to include property owners from more than 30 states, a roll call of Black mobility in the early 20th century. Families camped on their land the first few summers—canvas tents pitched between the trees—before the cottages went up: modest bungalows, log cabins, the occasional stone showpiece set back from the water.

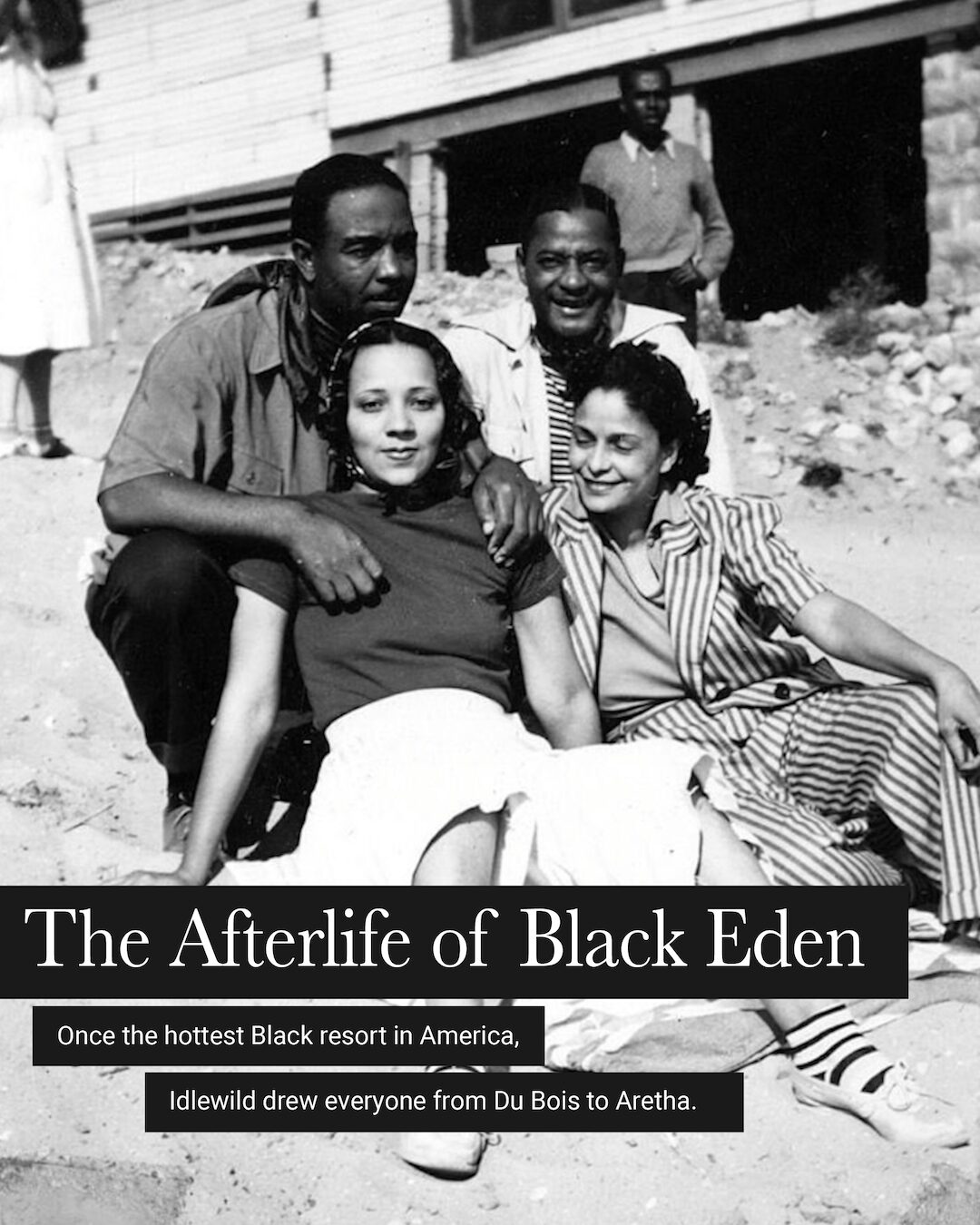

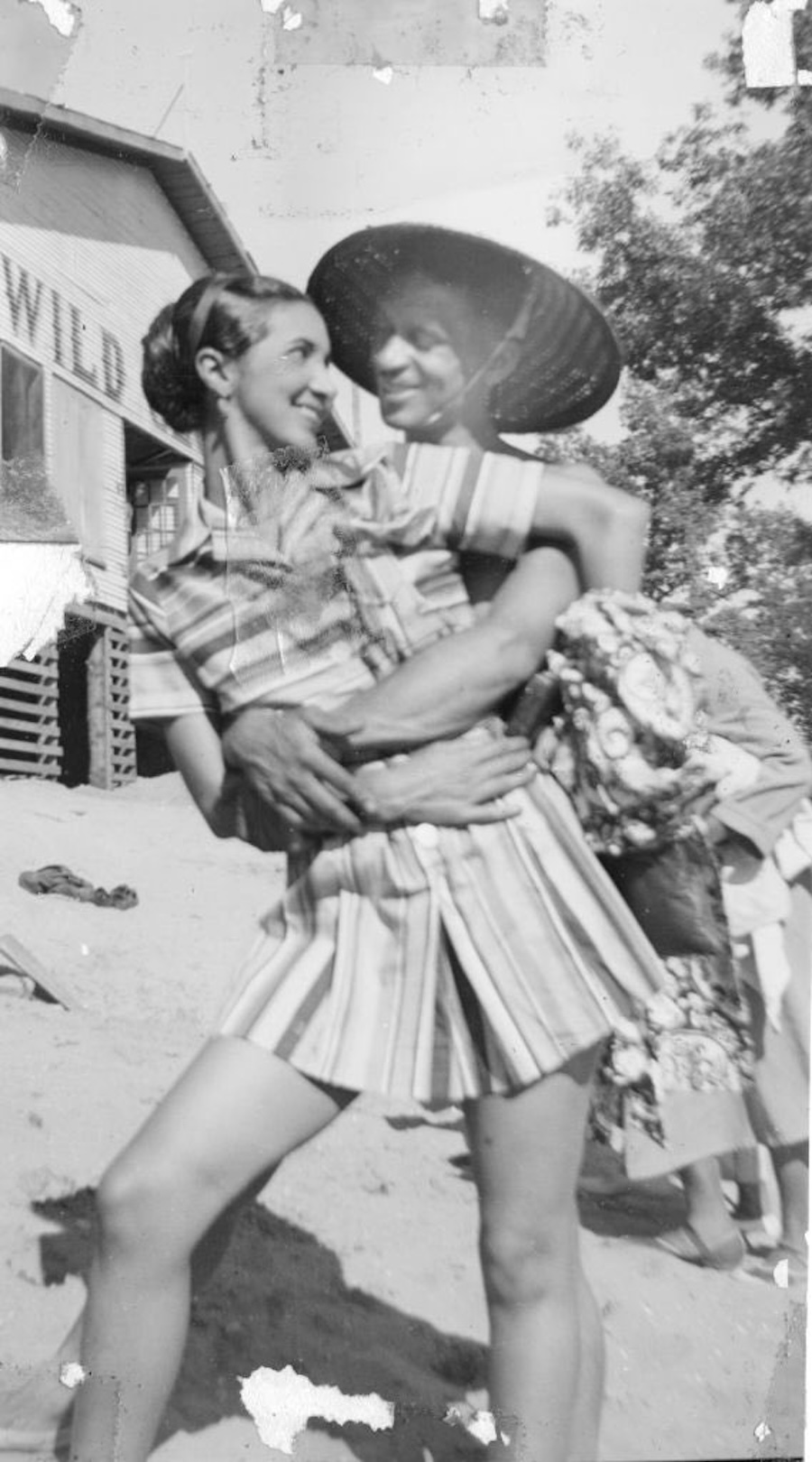

For those who came as children in the 1930s and ’40s, memories of those first summers linger like a soft focus family photograph. They remember paddleboats and horse rentals, long days of fishing and swimming, and parents who seemed to exhale as soon as the car rounded the last curve and the “Idlewild” sign came into view.

Jim Crow did not disappear at the state line. Many towns in northern Michigan were deeply segregated in practice if not in law. But within Idlewild’s boundaries, visitors recall an unusual kind of social ease. The historian Ronald J. Stephens has described it as a site where Black elites first gathered, but over time, the class lines blurred.

On the beaches and in the lake, you might see a Chicago judge and a Detroit auto-line worker grilling side by side. Children from wealthy families and those whose parents were still sharecropping in the South but managed one precious vacation shared the same swimming docks and bonfires.

The Making of a Nightlife Capital

By the late 1940s, as Black Americans’ incomes rose and the entertainment industry grew, Idlewild began to shift from a quiet vacation colony to one of the buzziest stops on the Black performance circuit.

Entrepreneurs built hotels and clubs with names that sounded like a promise: the Flamingo Club, the Purple Palace, the Paradise. Hotelier Phil Giles opened the Flamingo, while promoter Arthur “Big Daddy” Braggs turned the Paradise Club into an engine of spectacle powerful enough to export.

Braggs assembled showgirls and singers, comedians and bandleaders into polished revues that ran all summer in Idlewild, then toured the country in the off-season. His Idlewild Revue carried the town’s name on posters from Montreal to Oklahoma City, selling not just tickets but the idea of a northern Black utopia nestled in the woods.

A dancer named Carlean Gill, who performed at the Paradise in the early 1960s, later remembered that Idlewild was “fabulous… like New York or Paris.” White tablecloths, she recalled, the best steaks, and—perhaps just as important—an audience that included Black professionals from across the Midwest, dressed to the nines and ready to applaud.

The lineup of entertainers reads like a mid-century playlist: Sarah Vaughan, Dinah Washington, Duke Ellington, B.B. King, Etta James, Cab Calloway, the Four Tops, Jackie Wilson, the Temptations, Della Reese, Louis Armstrong, Aretha Franklin, and, later, Stevie Wonder.

Idlewild’s Casa Blanca Hotel became the unofficial headquarters for this cultural whirl. The largest hotel in town, it hosted both vacationers and the performers who worked the clubs at night. The National Trust for Historic Preservation would later describe how Black families spent their days fishing, picnicking and swimming before returning to Casa Blanca, where the Supremes, Sammy Davis Jr. and Della Reese might be staying down the hall.

For performers, Idlewild offered something rare. Della Reese, who sang here for seven consecutive summers, contrasted it with the Vegas of her early career: in Nevada, she could sing in certain casinos but not eat or sleep there. In Idlewild, she would later recall, she could “do anything [she] wanted to do,” a small but profound freedom for an artist who spent much of her life navigating segregated green rooms and back doors.

The historian Stephens calls the 1950s and early ’60s Idlewild’s “entertainment era,” when the resort became known not only as Black Eden but as the “Summer Apollo of Michigan” or the “Apollo of the Midwest.” The clubs operated as both local businesses and nodes in the national “chitlin’ circuit” that sustained Black performers shut out of white venues.

Bankers, Bar Owners and the Business of Joy

Behind the bright marquees and neon beer signs was an intricate Black economy. As many as 300 Black-owned businesses—from barbershops to cafes, taxi services to rooming houses—served the crush of summer visitors.

Local narratives are full of double lives. A banker from Detroit might spend his weekdays in a conservatively cut suit, then moonlight as the owner of a small Idlewild tavern where he extended informal credit to vacationers short on cash—an off-the-books economy of trust and tabs. A bar owner like Arthur Braggs juggled the numbers from his club with the more precarious business of scouting new acts, betting that a singer just starting out in Idlewild might soon be headed for Motown.

In oral histories and interviews, property owners talk about the resort as a kind of parallel financial system. You bought your lot on an installment plan marketed through Black newspapers. You borrowed against your house in Detroit to build a cottage, then rented out rooms there to cousins, church members, or strangers who became friends. When big weekends rolled around—Fourth of July, Idlewilders Club reunions—the streets became a marketplace of home-cooked food, informal child-care, and personal services.

Idlewild’s customers weren’t bank clients in the conventional sense, but many of them were managing mortgages and small-business loans back in their home cities. Vacation savings accounts at Black-owned banks quietly underwrote those weekends at the lake. The town’s prosperity was bound up with the aspirations of urban Black middle- and working-class families who used every tool at their disposal—savings clubs, fraternal organizations, church funds—to carve out a few weeks of rest in a country that rarely afforded them any.

“Jim Crow didn’t exist in Idlewild,” one retrospective from the local Historic and Cultural Center put it. Black and white patrons sometimes sat side by side in the clubs, a striking contrast to the rigid segregation that defined most of the Midwest. But it was Black money—and Black planning—that made the town function.

The Long Shadow of Freedom

The same Civil Rights Act that toppled Jim Crow across the South helped undo Idlewild.

By the mid-1960s, Black families who had once driven straight north now had options: Florida beaches, Las Vegas casinos, integrated national parks and resort chains that had previously refused them. Air travel got cheaper. Younger travelers wanted to see the world, not just the familiar lake where their parents had honeymooned.

One longtime visitor, Carolyn Stevens, who first came to Idlewild as a baby, put it bluntly: once Black families could go other places, “we left.”

For towns whose very existence depended on segregation’s exclusions, this freedom was both victory and economic catastrophe. The clubs struggled to fill their rooms; some closed outright. Cottages fell into disrepair, their taxes unpaid. Jobs at hotels, gas stations and shops disappeared. By the 1970s, the year-round population had dwindled to a few hundred people, mostly older residents who either couldn’t or wouldn’t leave.

Among them was John Meeks, a Detroit-born retiree who first came to Idlewild in 1954 and later made it his full-time home. In a 2012 profile originally published in the Financial Times, Meeks described building a small park near the lake as a personal centennial project. His T-shirt read, simply, “Idlewild, Michigan: The Black Eden.” He gave visitors informal tours, pointing out the boarded-up Casa Blanca Hotel, the vanished Paradise Club, and the modest house where Dr. Williams once spent his summers.

For Meeks and others, this was not nostalgia for segregation but a stubborn insistence that the joy created under those conditions deserved preservation—that the site of Black pleasure and self-determination was itself historic.

Holding on to Black Eden

If Idlewild was “dormant,” as one community organizer put it, it was never entirely asleep.

In 1979, the Idlewild Historic District was listed on the National Register of Historic Places, a first step toward formal recognition. The Idlewild Historical and Cultural Center opened in 2003, giving visitors a place to see photographs, posters and sequined costumes, and to hear directly from elders who remembered the town’s heyday.

Preservationists and artists took notice. Exhibitions like “Black Eden: Idlewild Past, Present, and Future” in Michigan museums paired archival images—laughing friends on the beach, families posing before clapboard cottages—with contemporary artworks, insisting that Idlewild was not just a relic but part of an ongoing conversation about Black leisure and land.

National organizations followed. The National Trust for Historic Preservation’s African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund awarded a $100,000 grant in 2023 to help stabilize and restore the Casa Blanca Hotel, with an eye toward reopening it as a functioning hotel by 2026. The Trust has since named Idlewild one of the nation’s “most endangered historic places,” arguing that saving sites of Black joy is a radical act in a country more accustomed to preserving battlefields than dance floors.

Meanwhile, local efforts have multiplied. The National Idlewilders Club, with chapters in several cities, continues to organize reunions that fill the town with second- and third-generation “Idlewilders” every summer.

On Dr. Daniel Hale Williams Island, the annual Idlewild Juneteenth Festival now draws visitors from across Michigan with music, fashion shows, history tours and a bonfire party that lasts into the night. And at the TEEM Center—Train, Educate, Equip and Mentor—founded in 2024 by Kyle and Carmen Grier, a new generation of local kids attends poetry nights, trade workshops and wellness sessions in a building whose mission is explicitly tied to Idlewild’s legacy as a Black cultural hub.

The Griers both grew up in Idlewild. They know first-hand the jarring contrast between the stories elders tell—of packed clubs and crowded beaches—and the quiet winters when the town’s few year-round residents watched roofs cave in under snow. Their bet is that the same thing that animated Black Eden in 1912—the desire for a place of one’s own—can still power its revival, even if the form looks different: community centers instead of cabarets, festivals instead of supper clubs.

What Idlewild Remembers

Idlewild is sometimes grouped with other Black leisure sites—Oak Bluffs on Martha’s Vineyard, Atlantic Beach in South Carolina, Lake Ivanhoe in Wisconsin—that once offered refuge for travelers barred elsewhere. But it remains distinct in both scale and symbolism. It was not just a beach or a cluster of cottages; it was an entire town built around Black land ownership, where a national Black middle class made itself visible in swimsuits and Sunday best.

In the National Museum of African American History and Culture’s telling, places like Idlewild were where Black people could “temporarily escape” the humiliations of Jim Crow, riding horses and roller-skating by day, listening to stars like Louis Armstrong and Aretha Franklin by night. Yet the memories preserved in Idlewild’s scrapbooks and living rooms suggest something fuller: not just escape, but the creation of a parallel world.

In that world, a Black surgeon could own a summer home on a lake named in his honor. A Black woman could run a hotel that drew the Supremes. A dancer like Carlean Gill could work in a place that felt, as she put it, like “New York or Paris,” without having to pretend she didn’t notice the color line.

And children—so many children—could grow up believing that it was normal for a vacation town’s billboards, business owners and bandstands to be filled with people who looked like them.

Today, as preservationists argue over zoning rules and grant applications, and as local organizers try to keep festivals afloat on shoestring budgets, the town is grappling with a question: what does Black Eden mean in a world where legal segregation is gone but economic and environmental pressures are reshaping rural communities everywhere?

On a summer afternoon, if you stand on the shore of Idlewild Lake and squint, you can still see traces of the answer. The laughing groups on the sand. The faint outlines of long-gone docks. The old Casa Blanca, its brickwork slowly being mended, waiting to welcome guests again.

The resort that segregation built is now being rebuilt—slowly, imperfectly—by people determined to remember both the pain that made it necessary and the joy that made it unforgettable.