KOLUMN Magazine

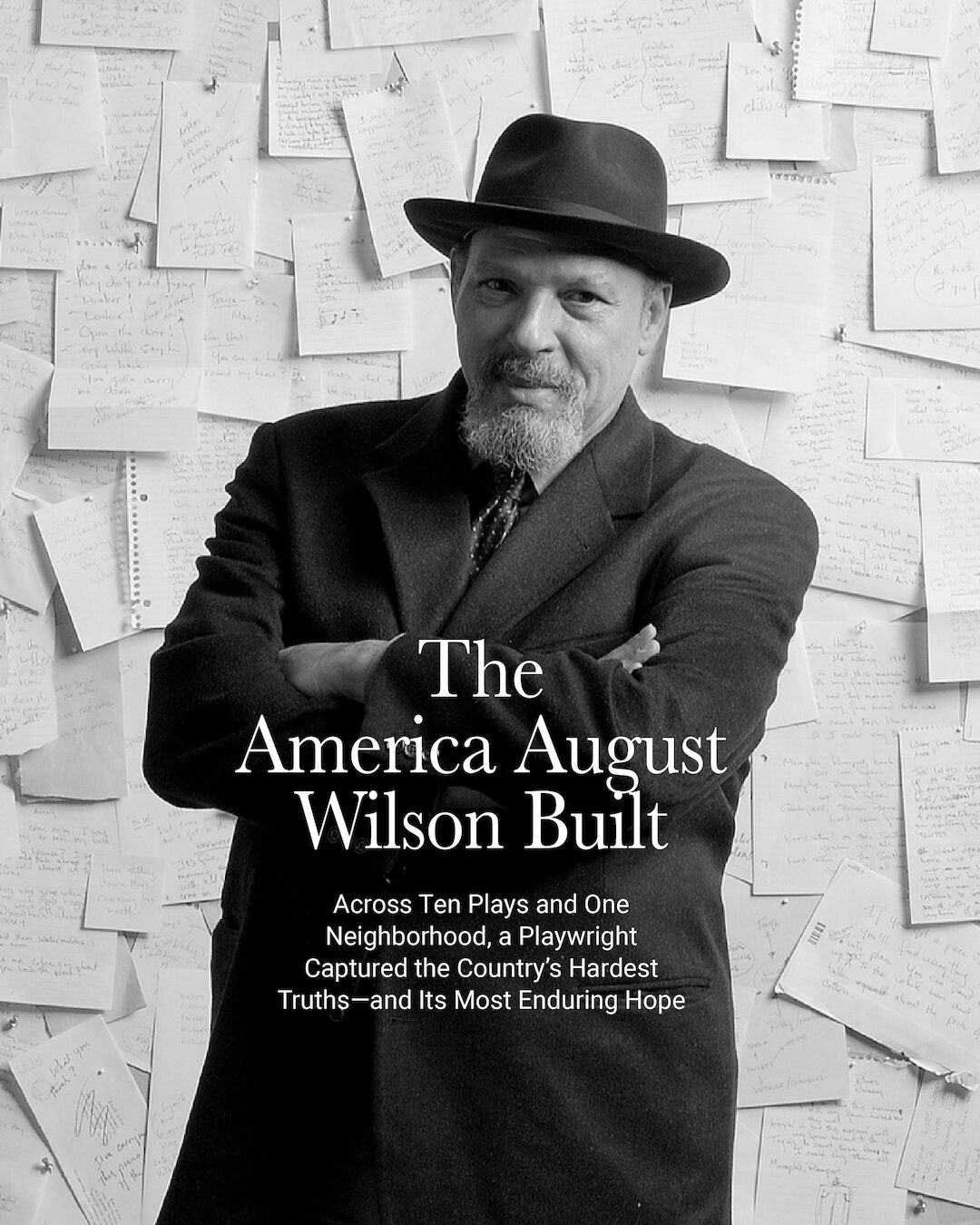

The

America August Wilson

Built

Across Ten Plays and One Neighborhood, a Playwright Captured the Country’s Hardest Truths—and Its Most Enduring Hope

By KOLUMN Magazine

In Baltimore, the lobby of a 300–seat theater hums with a kind of reunion energy. Families in Sunday clothes and students in hoodies crowd around a blown-up map of Pittsburgh’s Hill District, tracing streets with their fingers as if looking for an old address. Inside, on a modest stage at Arena Players, a woman called Aunt Ester is about to walk on in a white head wrap and a dress the color of deep water.

The play is Gem of the Ocean, set in 1904. It is the first chapter, chronologically, in August Wilson’s ten-play cycle about Black life in the 20th century, and the production is the opening salvo in Baltimore’s ambitious plan to stage the entire series, in order, over several seasons.

Nearly two decades after Wilson’s death in 2005, it can feel as if his characters are everywhere again—on Broadway, in regional theaters, in Denzel Washington’s film adaptations, in community companies determined to claim the cycle as their own. They are ex-ballplayers and jitney drivers, blues singers and janitors, women who scrub floors and call down the spirits; people who haunt barbershops, boarding houses, kitchens fragrant with collard greens.

For many in the Baltimore audience, the Hill District could just as easily be West Baltimore or southeast D.C., a neighborhood they know in their bones. That’s partly the point. Wilson’s grand experiment—what he called his “cycle of black life in America”—was rooted in a few hilly streets above downtown Pittsburgh and, at the same time, as expansive as the century itself.

The hill that became a universe

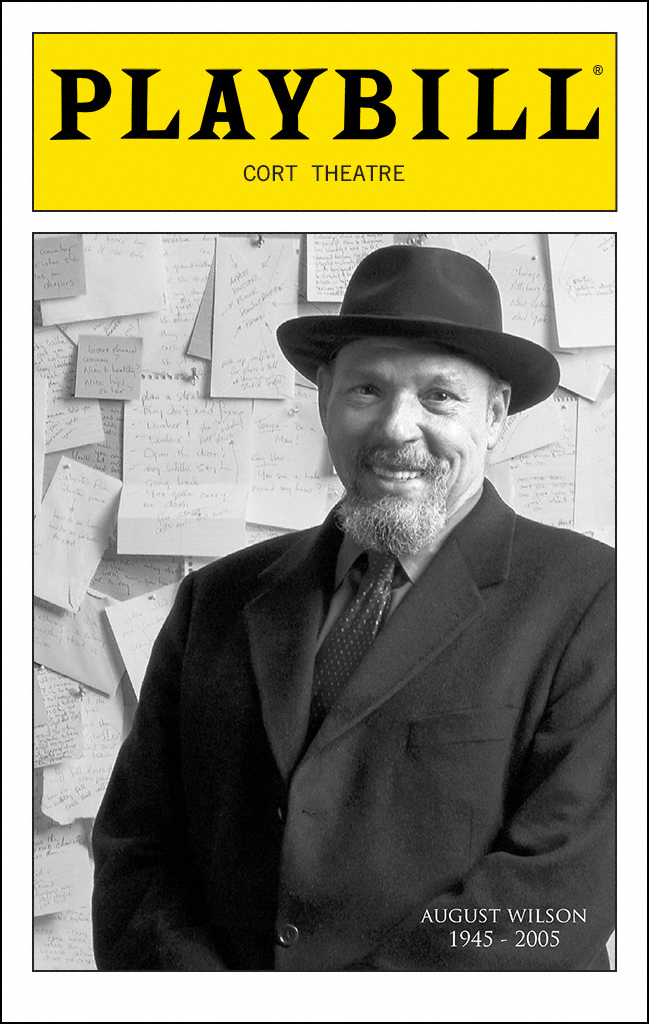

Before he was August Wilson, he was Fredrick August Kittel, a light-skinned boy born in 1945 in Pittsburgh’s Hill District to Daisy Wilson, a Black cleaning woman whose parents had migrated from North Carolina, and a German baker father who drifted in and out of the family’s cramped apartment.

The Hill was then a dense, working-class neighborhood, a crucible of Black migration and culture. Jazz clubs pulsed until dawn; storefront churches preached salvation and mutual aid; pool halls and corner bars functioned as informal employment offices and news bureaus. Sociologists and journalists called it “the crossroads of the world” for Black Pittsburgh.

Wilson’s formal education stopped early. After a white teacher accused him—without evidence—of plagiarizing a paper, he left high school and finished his education in the Carnegie Library, devouring history, sociology, poetry. He listened even more than he read. Friends remember him walking the Hill’s streets for hours, lingering in coffee shops and barbershops, filling notebooks with snatches of talk.

Those conversations—the mordant humor, the long, looping stories, the cautionary tales—became the raw material of his plays. Critics would later marvel at how completely his dramas are anchored in place: the Hill District as a recurring set, a community that ages and transforms as the decades roll by.

He didn’t consciously set out to write a century. In the early 1980s, when Jitney was playing in small houses and Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom was still a work-in-progress about a volatile recording session in 1927 Chicago, Wilson noticed that each play seemed to be gravitating to a particular decade. Eventually, the pattern became a vow: ten plays, one for each decade of the 20th century, most of them set on those same Pittsburgh streets where he had once eavesdropped.

Ten decades, one neighborhood

The resulting body of work—known as the Pittsburgh Cycle or the American Century Cycle—has few parallels in American letters. Starting in 1904 and ending in 1997, the plays track not presidents and wars but Black steelworkers, domestics, hustlers, small-time entrepreneurs and dreamers whose lives intersect with the country’s great upheavals: migration, industrialization, the Depression, the civil rights and Black Power movements, deindustrialization and gentrification.

Chronologically, the cycle begins in mysticism.

“Gem of the Ocean” (1900s): a journey to the City of Bones

In Gem of the Ocean, the Hill District is still fresh ground for a people who have only recently escaped slavery. At 1839 Wylie Avenue lives Aunt Ester, a spiritual guide said to be 285 years old, who carries in her memory the weight of centuries. She shepherds a troubled young man on an imaginary voyage to the City of Bones, an underwater realm built from the bodies of enslaved Africans lost in the Middle Passage.

The play is Wilson’s most overtly spiritual—and his most explicit about the afterlife of slavery. Its characters speak of chain gangs and stolen labor, of trying to build something solid on land that still feels like a promise, not a guarantee.

“Joe Turner’s Come and Gone” (1910s): searching for names

By the time Joe Turner’s Come and Gone arrives, set in 1911, the Hill is filling with lodgers from the South, men and women who carry scars from convict leasing and peonage. A Pittsburgh boardinghouse becomes a crossroads where migrants look for work, family, and, more abstractly, their names—identities not defined by the white officials who once wrote them into arrest ledgers.

The title refers to the real-life Joe Turney, a Tennessee official notorious for illegally impressing Black men into chain gangs—an echo of slavery in all but name. Wilson’s characters, still haunted by that system, are trying to claim something different: a sense of self that won’t disappear when a white employer snaps his fingers.

“Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom” (1920s): blues in a Chicago studio

The only play not set in Pittsburgh, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom unfolds in a 1927 Chicago recording studio, where the real-life blues star Ma Rainey battles white producers and restless band members over tempo, arrangements and, ultimately, control.

The distance from the Hill is geographic, not spiritual. The tensions are familiar: who profits from Black art, who owns the stories encoded in the blues. It’s also the first time Wilson trains his gaze on the Great Migration’s cultural consequences—what happens when Southern traditions are re-mixed in Northern cities under the cold eye of commerce.

“The Piano Lesson” (1930s): an argument carved in wood

If there is a single object that captures Wilson’s obsession with memory, it is the piano in The Piano Lesson, set in 1936. Carved with scenes of the family’s enslavement, the instrument becomes the focus of a blazing argument between siblings in their uncle’s Hill District house. Boy Willie wants to sell it to buy farmland in Mississippi, including the land once owned by the family that enslaved them; his sister Berniece refuses, insisting that to sell the piano is to sell their ancestors’ stories.

The debate is not just economic; it’s philosophical. Should the past be converted into capital, or guarded as sacred? Wilson doesn’t answer cleanly, but the play, which won him his second Pulitzer Prize, suggests that any future unmoored from history is fragile.

“Seven Guitars” (1940s): postwar blues

In Seven Guitars, set in 1948, the Hill is alive with postwar possibility. The central figure, blues musician Floyd “Schoolboy” Barton, comes home from jail with a hit record climbing the charts and a record company dangling promises. He is convinced that one more trip to Chicago will secure his future. His friends, battered by their own disappointments, are not so sure.

Here Wilson threads together two recurring motifs: the lure of mobility and the constraints of race and class. Floyd’s dream collides with the criminal justice system, with exploitative contracts, with the limits placed on Black men whose talent does not insulate them from police suspicion.

“Fences” (1950s): the walls we build

By 1957, in Fences, the Hill’s backyards are strung with clotheslines and half-finished fences. Troy Maxson, a former Negro League slugger turned garbage collector, wrestles with the bitterness of opportunities denied. The color line in Major League Baseball has finally broken, but too late for him. That thwarted promise curdles into a harsh kind of love toward his sons.

Fences earned Wilson his first Pulitzer and a Tony; decades later, Denzel Washington’s film adaptation would introduce Troy’s volcanic presence to a new generation of viewers.

Yet what lingers most in the play is smaller than awards or box-office numbers: the way Troy’s backyard conversations—with his wife, Rose; his sons; his war-scarred brother Gabe—trace the intersecting pressures of work, marriage, disability, and deferred dreams in an era often remembered, in mainstream narratives, as untroubled prosperity.

“Two Trains Running” (1960s): revolution and routine

If the 1950s play out in backyards, the 1960s unfold in a diner. Two Trains Running, set in 1969, takes place almost entirely in a Hill District restaurant facing demolition under urban renewal. Customers drift in and out, debating Malcolm X, the death of King, and whether city officials will ever pay fair prices for Black-owned buildings.

Outside, the country burns. Inside, the conversations are about rent, wages, prophecy, and the possibility of winning at the numbers game. Wilson’s genius is to show how epochal change coexists with the grind of everyday life—how revolutions are argued not only in mass meetings but over coffee refills.

“Jitney” (1970s): drivers on the margins

In Jitney, set in 1977, the action shifts to an unlicensed cab station serving parts of the city official taxis won’t enter. The drivers—Korean War veterans, ex-steelworkers, men who have squandered chances and are trying to piece together something like dignity—operate just outside the formal economy, ferrying their neighbors to factory shifts, grocery stores, hospitals.

The jitney station itself is threatened by redevelopment. The city wants to condemn the building; the drivers, who have little leverage, respond with gallows humor and quiet rage. The play captures the moment when industrial jobs are disappearing, leaving service work and hustles in their wake.

“King Hedley II” (1980s): selling stolen refrigerators in Reagan’s America

If Jitney is rueful, King Hedley II is raw. Set in 1985, it follows a man just out of prison, determined to stake out a future by selling stolen refrigerators and dreaming of opening a video store. The Hill District here is scarred by violence and limited options; crack and guns are background noise.

Wilson’s view is unsparing. The policies of the 1980s—mass incarceration, disinvestment—are not speeches but conditions, visible in the boarded-up houses and corner arguments. Yet he still carves out pockets of tenderness: a backyard garden painstakingly planted, a fragile hope that something new might grow.

“Radio Golf” (1990s): golf clubs and bulldozers

The final play, Radio Golf, lands in 1997, in a Hill District poised on the edge of gentrification. Harmond Wilks, a Black real-estate developer and would-be mayor, champions a redevelopment project that promises jobs, a Whole Foods, even a Starbucks. But to make the plan work, an old house—1839 Wylie, Aunt Ester’s address—must be demolished.

The conflict is no longer just between Black residents and white power brokers; it’s within the Black community itself, between an emerging professional class and those who fear being pushed out of neighborhoods they held together during leaner times. The cycle ends not with a clean resolution but with an argument about what progress looks like—and who gets to define it.

Making an epic out of ordinary lives

Across these ten plays, certain patterns emerge. Economically, the characters move from sharecropping and domestic work into factory jobs, then into service and professional roles. Politically, the world shifts from the grim afterlife of Reconstruction to civil rights marches to multicultural advertising campaigns. But the emotional terrain is stubbornly consistent: questions of responsibility, betrayal, faith, and what is owed to those who came before.

Wilson often described his influences as the “four B’s”: the blues, Jorge Luis Borges, Amiri Baraka, and painter Romare Bearden. From the blues he took the sense that sorrow and humor can occupy the same line; from Bearden, the idea of collaging fragments of Black life into a coherent whole; from Borges and Baraka, a respect for myth and for political urgency.

He also insisted that his plays were, first and last, about specific people in a specific community. When critics asked if he felt pressure to “represent” the Black experience, he pushed back. No one, he pointed out, asked white playwrights whether their Irish or Italian characters stood for their entire ethnicity. He was writing, he said, about “the culture of black Americans,” but doing so by paying close attention to individuals—their cadences, their stubbornness, their jokes.

That attention produced characters who feel startlingly alive even on the page. Boy Willie’s impulsive swagger, Troy Maxson’s digressive storytelling, Aunt Ester’s no-nonsense authority, the weary patience of women like Rose and Berniece—these are not types or symbols so much as people you might recognize at the bus stop.

A living canon

During his lifetime, Wilson’s work was showered with awards. In addition to his two Pulitzers—Fences and The Piano Lesson—he collected a Tony Award, a raft of New York Drama Critics’ Circle awards, a Peabody, and honorary degrees from universities that once might have hesitated to embrace a high-school dropout who wrote in longhand.

But the deeper measure of the cycle’s impact may lie in what’s happening now, years after his death.

Denzel Washington, who starred in and directed the 2016 film version of Fences, has pledged to shepherd film adaptations of all ten plays; Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom followed in 2020, with The Piano Lesson next in the pipeline. On stages, institutions from the Kennedy Center to regional theaters have mounted full-cycle festivals, while smaller companies—like Arena Players in Baltimore—take on the plays one by one, building local traditions around them.

The August Wilson African American Cultural Center in downtown Pittsburgh, meanwhile, mounts its own programming around the cycle, exhibiting photographs and artifacts from the Hill District and hosting conferences on Wilson’s legacy. An exhibition titled “A Writer’s Landscape” invites visitors to walk through set-like installations of a Hill District kitchen, a jitney station, a radio studio, suggesting that the line between history and theater is porous.

In universities and high schools, the plays have become staples of syllabi. Yet what keeps them from ossifying into homework is their rootedness in lived experience. Actors who return to the roles talk about feeling as though they are visiting relatives. Directors find themselves updating stage directions not by modernizing them but by leaning into the specificity of the era—tracking down period radios, hand-crank washing machines, vinyl-clad diner stools—not as nostalgia but as context.

And audiences, especially Black audiences, encounter something rarer: an extended universe in which their grandparents’ and parents’ lives are not side notes to American history but its organizing principle.

The hill, revisited

Back in Baltimore, after the final scene of Gem of the Ocean, the house lights come up slowly. For a moment, no one moves. Aunt Ester has just guided Citizen Barlow, the play’s troubled young man, through a harrowing vision of the City of Bones, forcing him to face both the crimes he has committed and the larger crimes of history.

When the applause finally breaks out, it’s loud and sustained. Yet the more telling moments happen later, in the lobby and on the sidewalk, where people compare the story onstage to stories from their own families: a great-grandmother who “could see things,” an uncle who drove jitneys, a brother who, like Troy Maxson, still talks about the inning when everything might have gone differently.

August Wilson never lived to see a world in which entire cities would organize festivals around his work, or where streaming services would bring his Hill District to living rooms far from Pittsburgh. He died, at 60, just months after finishing Radio Golf.

What he did see, and insist upon, was the intrinsic worth of the neighborhood that raised him. In an era when policy debates and cultural arguments often flatten Black life into abstractions—“the inner city,” “urban voters,” “the Black community”—Wilson’s ten-play cycle keeps returning to the granular: who’s behind on the light bill, which cousin is sleeping on the couch, who’s mad at whom over a long-ago insult.

Taken together, the plays form a century-long ledger, not of debts and assets in the financial sense, but of obligations—between parents and children, neighbors and neighborhoods, the living and the dead. They are, in that way, a kind of spiritual account book for a people navigating a country that has rarely balanced its own books.

On the Hill today, many of the settings that inspired Wilson have been demolished or remade. The jitney stations have thinned out; redevelopment has arrived in fits and starts. But in rehearsal halls from Pittsburgh to Baltimore to Los Angeles, actors are still learning his lines, trying on his characters’ jokes and fury and stubborn hope.

The plays are set in the last century. The arguments inside them—about land and memory, work and worth, who gets to decide the future of a neighborhood—belong very much to this one.