KOLUMN Magazine

Seats of

our own

Before multiplexes and streaming, Black audiences carved out their own cinematic world—from William Brown’s African Grove Theatre to the Pekin and Greenwood’s Dreamland. The long fight to keep those doors open is still not over.

By KOLUMN Magazine

In Macon, Georgia, the Douglass Theatre’s neon sign flickers back to life.

Inside, the crowd is small but insistent—grandmothers in church dresses, teenagers in sneakers, a man in a ball cap with “Black Wall Street” stitched across the front. They’ve come to watch a restored print of a 1920s “race film,” projected in a Black-owned theater that first opened its doors in 1921 and nearly lost them for good in the 1970s. The building, once dormant for two decades, was rescued by community organizers and reopened in 1997 as a state-of-the-art performance and cinema venue.

The film crackles, the picture jumps. On screen, a Black couple walks into a movie house where every seat is filled with faces like their own. It’s an ordinary scene, and in that ordinariness lies the radical promise of a whole parallel history: Black-owned and Black-run theaters, scattered across the country, where Black people could sit where they chose, see themselves centered onstage and onscreen, and do so in a space that answered to them.

Most of those theaters are gone. A few—like the Douglass—are being painstakingly restored. Others, like the Jewel Theater in Oklahoma City, are mid-resurrection, celebrated as the last historically Black-owned theater in their state. Many more lie in ruins or beneath parking lots, victims of urban renewal, disinvestment, or a highway driven straight through Black neighborhoods.

Yet if you follow their faint, persistent trail back through time, the story does not begin with cinema at all. It begins with a tea garden in lower Manhattan in 1821, where a free Black man from the West Indies decided to build a stage.

The Grove

On summer evenings, William Alexander Brown’s backyard filled with sound.

Brown, a retired West Indian steamship steward, had bought a house on Thomas Street in New York City and turned it into an informal gathering place. In the yard, he hosted poetry readings, musical performances, and small plays expressly for Black audiences—free and enslaved, working- and middle-class. It was a fragile oasis in a city whose gradual abolition of slavery would not be complete until 1827.

By 1821, Brown was ready to formalize what he’d started. He moved to a larger house at Mercer and Bleecker, on the edge of the developed city, and converted its second floor into a 300-seat theater. He called it the African Grove Theatre.

Inside the Grove, the rules flipped.

On the city’s main stages—most notably the Park Theatre—Black people, if admitted at all, were consigned to the worst seats. At the African Grove, seating was organized for Black comfort and visibility. Whites could attend, but they were relegated to a roped-off section at the back, an inversion that white critics at the time called “insolence.”

On a typical night, a composite of accounts suggests, the show might begin with music—fiddles and drums, familiar songs altered by Caribbean and Southern rhythms—before the actors took the stage. The company adapted Shakespeare, notably Richard III, for a small troupe and smaller budget. An early reviewer described the “dapper, woolly-haired waiter” who played the title role, later identified by scholars as James Hewlett, one of the first known Black Shakespearian actors.

The Grove did more than reinterpret Shakespeare. Brown wrote his own work, including a now-lost play, The Drama of King Shotaway, widely believed to be the first full-length play by a Black American performed in the United States. It dramatized an anti-colonial uprising in the Caribbean, linking Black struggles for freedom in the Americas across land and sea.

From the start, the theater was under siege. Neighbors complained about noise; police made frequent visits. When Brown moved his operation near the prestigious Park Theatre, staging a rival Richard III next door on the same night, the conflict turned open. The Park’s white owner, Stephen Price, reportedly financed disruptions that gave authorities the pretext to shut down the Grove.

Within a few years, the African Grove was gone—its building demolished, its props and costumes scattered. Its impact, though, rippled outward. It proved that Black people would pay to see themselves onstage and that they could run their own theatrical enterprises. It established a template: a Black-controlled space, in a hostile city, where art and business and community overlapped.

A century later, that template would be reborn in Chicago, with a new name over the door: The Pekin.

The Temple of Music

On June 18, 1905, in what Chicago newspapers then called the “Black Belt,” a rowdy South Side saloon went dark.

The Pekin Saloon and Restaurant, known more for gambling than culture, was being transformed. Its owner, Robert T. Motts—a former saloonkeeper and “policy king” who had made a small fortune in the city’s underground numbers racket—closed up shop and reopened as the Pekin Theatre, the first Black-owned musical and vaudeville stock theater in the United States.

Motts called it his “temple of music.” Where white-owned downtown venues relegated Black patrons to balconies or barred them outright, the Pekin let Black Chicagoans sit wherever they wanted. The staff—from ushers to managers—was entirely Black, defying conventional wisdom that Black people lacked the “temperament” for theater management.

A typical night at the Pekin might begin with a ragtime overture from the in-house orchestra, followed by one of the theater’s original musical comedies—titles like The Man from ‘Bam, The Mayor of Dixie, or The Husband. Between acts, comedians and dancers worked the stage; upstairs, in the boxes, middle-class families from the neighborhood’s growing professional class—barbers, Pullman porters, schoolteachers—leaned forward in their seats, watching.

For them, the Pekin was more than a diversion. It was a place to see versions of themselves rarely visible elsewhere. Black playwrights experimented with scripts that, while imperfect by modern standards, attempted to move beyond minstrel caricature into local satire and aspirational middle-class worlds.

The Pekin also became a training ground. Actors, directors, and musicians circulated through its stock company, building careers that would ripple across Black theater for decades. Historian Thomas Bauman has described the theater as “renowned for its all-black stock company and school for actors, an orchestra able to play ragtime and opera with equal brilliance, and a repertoire of original musical comedies.”

Then the motion picture arrived.

By 1908, interest in live vaudeville was giving way to the novelty of projected moving images. The Pekin struggled to adjust, even as a new Black-run film ecosystem slowly took shape. William Foster’s Foster Photoplay Company, often described as one of the first Black-owned film production companies, drew talent directly from the Pekin’s stage for its 1913 comedy The Railroad Porter, considered among the earliest films produced and directed by an African American with an all-Black cast.

The Pekin remained, for a time, a hybrid space—live performance, early film, a social club where South Side Chicagoans debated politics and baseball. After Motts died in 1911, the theater’s fortunes waned. A fire led to expansion and a new name, the New Pekin, but by the early 1920s it had closed. The building was demolished in 1946.

Still, the idea Motts had nurtured—a grand, Black-owned entertainment house that anchored a business district—would travel west and south, toward oil boom towns, railroad cities, and one square mile of Oklahoma land that would be called Black Wall Street.

Dreamland

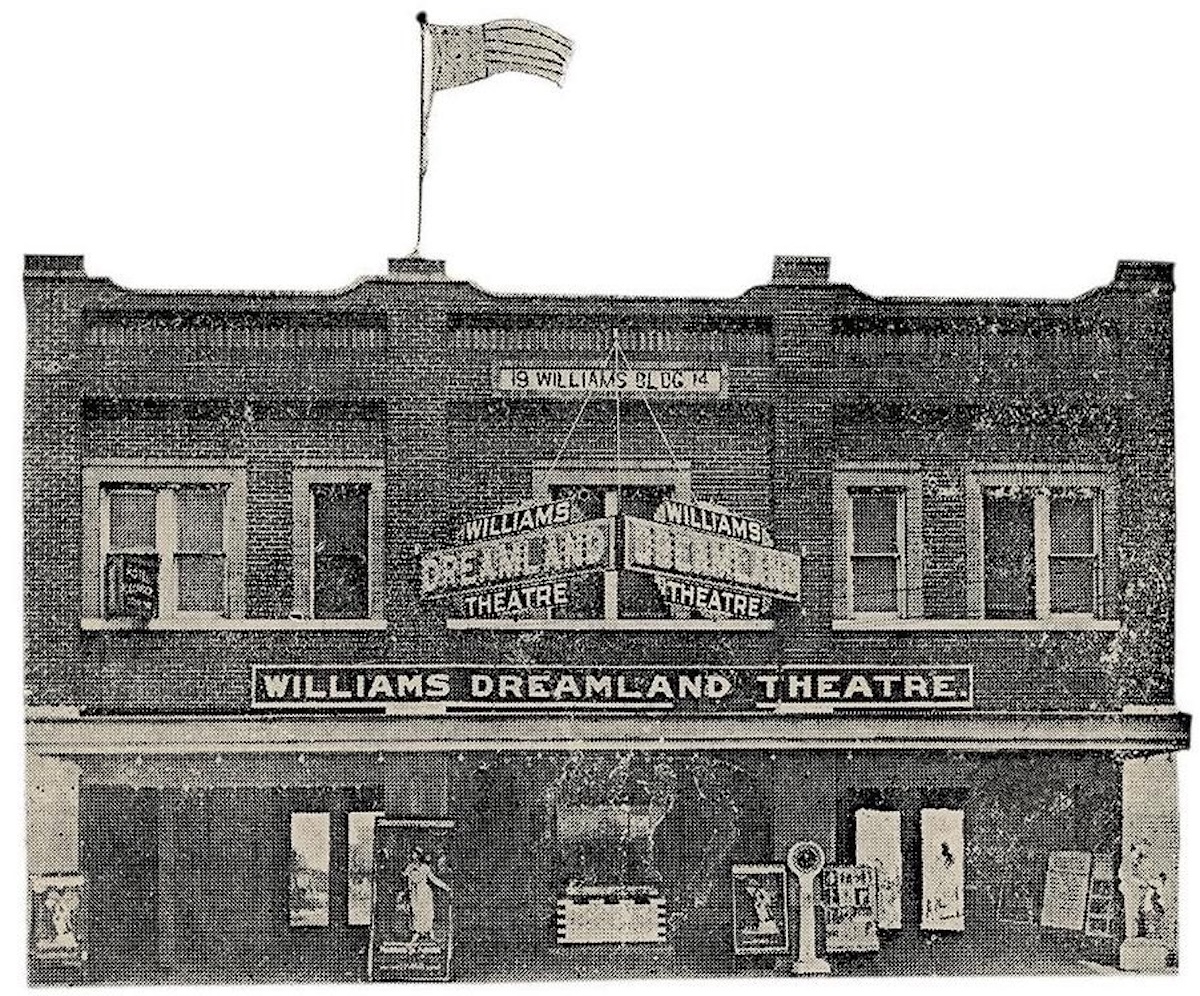

On a summer night in 1921, the Williams Dreamland Theatre in Tulsa, Oklahoma, doubled as a war room.

Just seven years earlier, John and Loula Williams had opened the theater on North Greenwood Avenue, in the heart of a neighborhood so prosperous it was nicknamed Black Wall Street. Their Dreamland, part of a three-theater chain that stretched to Okmulgee and Muskogee, offered live performances and silent films to as many as 750 patrons at a time. It was, by one historian’s account, among the most profitable Black-owned businesses in the state, helping build a family net worth estimated at $150,000—roughly $2.2 million in 2021 dollars.

On ordinary evenings, the Dreamland functioned much like the Pekin: a place where Black patrons could sit where they liked, watch performers from the Theatre Owners Booking Association circuit, and see motion pictures while avoiding the humiliation of Jim Crow seating downtown. On special nights, the Williamses projected films by Black director-producer Oscar Micheaux; a century later, HBO’s Watchmen would imagine a dream premiere of a Micheaux film about U.S. Marshal Bass Reeves in the Dreamland’s darkened hall.

But on May 31, 1921, the Dreamland took on a different role.

That evening, rumors were spreading that a young Black man, Dick Rowland, would be lynched after reported false allegations about an incident in a downtown elevator involving himself and a white woman. Black veterans, many of them recently returned from World War I, gathered at the Dreamland and in nearby businesses to debate how to respond and whether to go armed to the courthouse.

By the next day, white mobs had descended on Greenwood. Airplanes dropped incendiaries; machine-gun fire raked the streets. The Dreamland, like the rest of Black Wall Street, was looted and burned. Photographs from June 1, 1921, show the theater’s skeletal remains, a jagged facade against an empty sky.

For survivors, the theater became fixed in memory as both sanctuary and target. In oral histories collected decades later, elders recalled hiding in the vicinity of the Dreamland or fleeing past its ruins. Writers and artists at the 2021 centennial evoked the theater again and again—“Dreamland” became shorthand not just for a building, but for a world of Black prosperity violently interrupted.

Remarkably, the Dreamland was rebuilt in the 1950s, a testament to Greenwood’s stubborn refusal to disappear. It lived a second life before being erased again—this time not by mob violence, but by urban renewal. In the 1970s, Interstate 244 carved through the district, and the theater was demolished. Today, a small plaque marks the site where one of Black America’s grandest movie houses once stood.

A century after the massacre, local advocates launched “Dreamland Rising,” an effort to reimagine the theater as part of a broader Greenwood revival. Their work sits at the crossroads of memory and real estate, trying to rebuild not just a facade but the sense of safety and self-definition that movie houses like Dreamland once offered.

The Segregated Screen

By the 1920s, Black-owned theaters like the Pekin and Dreamland were part of a dense, if fragile, ecosystem.

In the years between World War I and World War II, the popularity of “race films”—movies made for Black audiences and often (though not always) by Black producers—helped sustain a network of Black cinema houses. Historian accounts describe “an abundance of Black-owned film studios and a multitude of exhibition venues including Black-owned movie houses like the Howard Theatre in Washington, D.C., and neighborhood cinemas in cities from Baltimore to Dayton.”

In Baltimore, the Royal Theatre began in 1922 as the Black-owned Douglass Theatre, specializing in movies and Black vaudeville. It soon became a stop on a national circuit that linked Black entertainment districts in big cities—Harlem’s Apollo, Washington’s Howard, Chicago’s Regal, Philadelphia’s Earl. In Chapel Hill, North Carolina, the Standard Theater, opened in 1924, was owned and operated by Black entrepreneur Durwood O’Kelly and his partners, doubling as a movie house, social hall, and church space for congregations without their own buildings.

Some of these theaters were monumental. Dayton’s Classic Theater, opened in 1927 and believed by some local historians to be the first Black-built, Black-operated, and Black-owned theater in the United States, boasted 500 seats, a balcony, an upstairs ballroom, and a custom Wurlitzer organ. Its owners advertised it with the slogan: “It’s Your Theater.”

Yet even as Black entrepreneurs carved out pockets of control, the wider moviegoing world remained harshly segregated. In much of the South and parts of the North, Jim Crow dictated separate entrances, separate restrooms, separate seating—or separate theaters altogether. A 2022 article on Southern movie culture describes the way segregation was written into the physical layout of theaters and, by extension, the social order of towns: balconies marked “colored,” ticket lines split by race, “midnight rambles” where Black audiences were allowed into white theaters only after regular hours.

Black journalists, pastors, and civic leaders saw clearly what was at stake. Segregation at the movies, they warned, was not just about entertainment; it bled into every aspect of urban life, reinforcing discrimination in restaurants, parks, even schools.

For Black patrons, the experience was double-edged. In some cities, white-owned “colored houses” played race films but answered ultimately to white managers and distributors. In others, fully Black-owned theaters became testing grounds for community life. A teenager might sneak into the balcony for a Saturday matinee; a lodge might rent out the space for a fundraiser; a church, locked out of downtown halls, might hold special services there on Sundays.

Seen together, these spaces formed a parallel public sphere—one linked not only by films and touring performers but by booking networks like the Theatre Owners Booking Association (TOBA), which by the mid-1910s strung together more than twenty Black-owned or Black-operated theaters from Atlanta to the Midwest.

The Long Fade

The forces that built this world also contained the seeds of its undoing.

In the 1940s and 1950s, as Hollywood consolidated its power and television entered American homes, neighborhood theaters—Black and white—felt the squeeze. At the same time, the slow collapse of de jure segregation created both opportunity and peril.

Civil rights activists rightly targeted segregated theaters as fronts in the struggle for equality. Students organized “stand-ins” and boycotts of whites-only cinemas from Chapel Hill to Tallahassee, confronting movie houses over racist seating policies and broader patterns of exclusion. When the Civil Rights Act of 1964 finally outlawed segregation in public accommodations, Black audiences gained access to downtown first-run houses from which they’d long been barred.

But integration carried a hidden cost. As one Golden Globes history of Black cinema notes, the end of official segregation also hastened the decline of a distinctive Black cinema infrastructure. Many Black movie houses lost customers to larger, better-financed mainstream theaters. Others were casualties of white flight and urban disinvestment.

In Black neighborhoods across the country, the closing of a local movie house usually did not make front-page news. A marquee went dark; a box office window was boarded up. Sometimes, as in Baltimore, a wrecking ball followed. The Royal Theatre was demolished in 1971; the Douglass name survived only on plaques and in memories of dancers and bandleaders who once worked its stage.

In other places, the buildings survived by transforming. Los Angeles’s Lincoln Theater, sometimes called the “West Coast Apollo” for its line-up of Black performers, became a church in 1962 and continues to host religious services. On U Street in Washington, D.C., a different Lincoln Theater was reborn as a performing arts venue after years as a movie house and decades of closure, its marquee a reminder of segregated nights when Black Washingtonians could claim at least one grand theater as their own.

When neighborhoods gentrified, the pressure shifted again. Developers and nonprofits eyed old theaters as potential condos, community centers, or simply parcels of land. In Houston, preservation advocates have recently battled plans to demolish the historic Granada Theater—one of the few inclusive venues that once welcomed Black and Hispanic audiences—to make way for a Family Opportunity Center. Supporters of the deal argue the new facility will provide crucial social services; opponents warn that erasing the theater erases a chapter of community history.

The pattern is familiar to anyone who has tracked Black spaces in American cities: churches, barbershops, nightclubs, amusement parks, and, yes, movie theaters, each pulled between survival and erasure, between memory and the demands of the present.

What Survives

And yet, as the Douglass Theatre’s flickering screen suggests, the story of Black-owned movie theaters is not purely one of loss.

In Macon, the Douglass now advertises digital cinema, educational children’s performances, and community events alongside retrospectives of classic films. It is, as local promoters like to say, “true to its historic reputation as a magnet for the entire community,” its programs designed to draw “widely-varied audiences” into a space once reserved for Black patrons alone.

In Oklahoma City, the Jewel Theater—Oklahoma’s only remaining historically Black-owned theater—is undergoing a careful restoration, backed by local leaders and descendants of its original owners. When it reopens as a dual movie and performing arts venue, it will stand as both a monument and a working space, part of a broader effort to revitalize the Deep Deuce district without erasing its past.

The revival efforts are not confined to the United States. In London, the Electric Cinema in Notting Hill briefly became Britain’s first Black-owned cinema in 1993, before changing hands again in 2000. And in the Baltimore suburbs, Next Act Cinema bills itself as the first Black-owned movie theater in the area in the contemporary era, combining luxury seating with a mission to make cinema feel like a family living room.

Notably, when Ryan Coogler’s film Sinners—a juke-joint thriller about Black refuge and racial terror—returned “home” to Clarksdale, Mississippi, this year, the celebration unfolded not in a local movie house but in a pop-up festival, precisely because the town has no functioning theater of its own. The three-day event, sponsored by a major studio and energized by local organizers, underscored both the enduring power of cinema and the structural absence that Black-owned and Black-serving theaters once filled.

These efforts are piecemeal and precarious. They depend on grants, volunteer boards, the willingness of developers to compromise. But they also show that when communities fight for their theaters, they are not simply protecting brick and plaster. They are defending a way of seeing themselves.

The Long Arc from Grove to Dreamland

Taken together, the African Grove Theatre, the Pekin, and the Williams Dreamland Theatre chart a long arc of Black control over the spaces where stories are told.

At the Grove in 1821, William Brown envisioned a theater built by and for Black people at a time when slavery was still legal in the state and white mobs could shut him down with a single police raid. At the Pekin in 1905, Robert Motts turned gambling profits into a “temple of music,” hiring Black managers and technicians and inviting South Side audiences to claim every seat in the house. In Greenwood in 1914, Loula and John Williams built Dreamland into the “crown jewel” of a theater empire—only to watch a mob try to erase it in a matter of hours.

Each enterprise came under attack—by racism, by fire, by economic pressures—and each left behind more than charred beams or dusty playbills. They left behind a template that contemporary organizers still draw from: the idea that controlling the venue where stories are told is as consequential as controlling the story itself.

For generations of ordinary Black moviegoers and theater fans, these were not abstractions. They were date nights and Saturday matinees, first jobs and side doors into the arts. A teenager usher at the Royal in 1940s Baltimore who watched Cab Calloway from the back of the house; a Pullman porter in 1910s Chicago who spent his tip money on Pekin tickets; a Greenwood seamstress in 1920 who slipped into Dreamland after her shift to watch a melodrama—each moved through spaces that signaled, however imperfectly, that their presence mattered.

Historians of Black cinema rightly focus on directors and stars, on Oscar Micheaux and Dorothy Arzner, on race films and Blaxploitation. But behind those reels stands a quieter infrastructure of owners, managers, and audiences who built, maintained, and sometimes rebuilt the rooms where the light hit the wall.

Today, as debates about representation in Hollywood and streaming shift from red carpets to union halls and boardrooms, the physical theater can seem almost quaint—a nostalgic relic in an era of on-demand content and living-room binge-watching. And yet the rush to save places like the Douglass, the Jewel, and the last remaining Black-serving houses in cities like Los Angeles suggests something else: that there is still power in gathering in the dark with strangers, in a building that remembers you.

In that sense, every effort to reopen a Black-owned theater is also an attempt to reopen a conversation that began two centuries ago in a small New York backyard, where a free Black man from the Caribbean built a stage and invited his people to come and watch themselves.