The

Letter

That Changed Peanuts

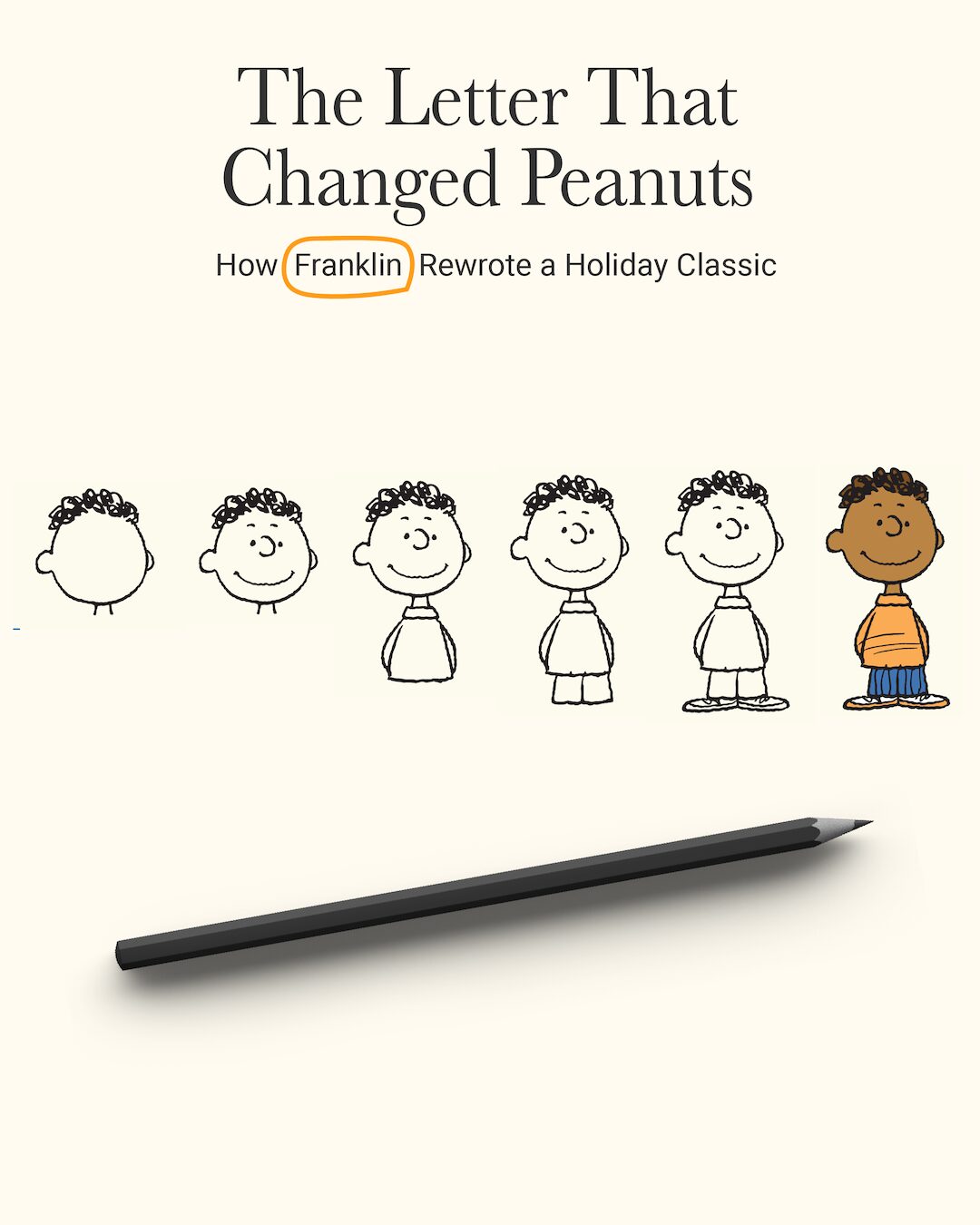

How Franklin Rewrote a Holiday Classic

By KOLUMN Magazine

On millions of American screens every November, the scene lasts only a few seconds.

The Peanuts gang crowds around a long outdoor table for an improvised holiday meal. Charlie Brown sits near the middle. Linus, Peppermint Patty, Marcie and the others face the camera, framed by jelly beans and popcorn. At the far edge, alone on one side of the table and perched in a striped lawn chair, sits Franklin — the only Black child in the frame.

In recent years, that single shot from A Charlie Brown Thanksgiving has been turned into a meme and a cultural Rorschach test. Is it a relic of casual racism, a clumsy oversight, or an artifact of a series that was, for its time, trying to push the conversation on race a little further than most children’s media dared?

To answer that, you have to start not with Thanksgiving, but with a letter written in the aching spring of 1968.

A Letter After an Assassination

On April 4, 1968, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis. Eleven days later, a white elementary school teacher in Los Angeles named Harriet Glickman sat down at her kitchen table and wrote to Charles M. Schulz, creator of Peanuts.

Glickman, a mother of three, had spent the previous days trying to help her students process what had happened. She believed mass media — and especially a comic strip as widely read as Peanuts — could play a quiet but powerful role in shifting how children saw one another. In her letter, she asked Schulz to consider introducing a Black child into his strip, arguing that such a character could help chip away at what she called the “sea of misunderstanding, fear, hate and violence” in American life.

Schulz wrote back quickly. He told her he had considered adding a Black character, but worried it might come across as condescending — that he might, as he later put it, “patronize our Negro friends.”

Instead of dropping the idea, Glickman widened the circle. With Schulz’s permission, she asked several Black friends and parents to write to him, explaining what it would mean to see their children reflected in his “little neighborhood” of characters. They did. Those letters, preserved today at the Charles M. Schulz Museum in Santa Rosa, California, pressed the point gently but firmly: representation in something as ubiquitous as Peanuts could matter, not in an abstract sense, but to real kids sitting in actual classrooms.

Within months, Schulz wrote back to Glickman with a brief, almost understated note: he was going to introduce a new Black character.

Franklin on the Beach

Franklin made his debut in the daily strip on July 31, 1968.

Schulz chose a setting that felt both ordinary and quietly political. The new kid meets Charlie Brown on a beach, returning a lost beach ball. In that first sequence, the boys build a sandcastle together and talk about their fathers; Franklin’s dad is serving in Vietnam, Charlie Brown’s is a barber who “was in a war too, but I don’t know which one.”

In an era when beaches in parts of the United States were still de facto segregated, two boys — one white, one Black — playing together in the sand was a subtle but unmistakable image of integration. Word In Black and associated outlets have noted that those early strips deliberately placed Franklin in integrated spaces that, in real life, were contested terrain.

For many Black readers, that quiet normalcy was the point. In later interviews, Glickman would recall meeting Marleik “Mar Mar” Walker, the young Black actor who voiced Franklin in The Peanuts Movie. Seeing him brought her to tears, she said, because he matched the child she had imagined when she wrote Schulz in 1968 — a boy who could simply exist in the story without being defined solely by racism.

“Print It Just the Way I Draw It or I Quit”

Franklin’s presence in Peanuts was not universally welcomed.

As the strip unfolded, Schulz began drawing Franklin in school with the rest of the kids. In one strip, Franklin sits in front of Peppermint Patty in a classroom. A Southern editor wrote to the syndicate objecting: he didn’t mind Schulz including a Black child, he reportedly said, “but please don’t show them in school together.” Schulz ignored the letter.

At another point, an executive at the syndicate urged Schulz to reconsider how he was handling Franklin, worried about controversy in certain markets. Schulz later recalled telling him over the phone, “Either you print it just the way I draw it or I quit. How’s that?” Franklin stayed.

The character himself was deliberately understated. He wasn’t a stereotype or a sermon; he liked hockey, told stories about his grandfather, and, like everyone else in Peanuts, delivered the occasional deadpan line about the absurdities of childhood. In contemporary assessments, scholars of comics have described this as a kind of “quiet radicalism”: Franklin wasn’t there to “solve” racism. He was there to belong.

Franklin Finds His Voice — and a Holiday

Franklin didn’t appear in animation until the early 1970s, beginning with a silent role in the 1972 feature Snoopy Come Home. His first speaking part came the following year in the TV special There’s No Time for Love, Charlie Brown.

Later that same year, Schulz wrote A Charlie Brown Thanksgiving, the third holiday special in the franchise. It debuted on CBS in November 1973 and went on to win an Emmy.

The special follows a familiar Peanuts pattern: Charlie Brown is roped into hosting a Thanksgiving meal he is wildly unprepared to cook; Snoopy constructs an elaborate outdoor dining setup and serves toast, popcorn, and jelly beans; Peppermint Patty complains; and the episode ends with a hastily re-routed trip to grandma’s real dinner table.

Franklin is one of the friends Peppermint Patty invites over — a small but symbolically significant inclusion. His presence makes him part of that imaginary ideal of American childhood, where kids of different races share the same rituals, holidays and disappointments.

Behind the mic, Franklin was voiced by Robin Reed, a Black child actor from California. Decades later, Reed recalled being “probably 11 or 12” when his agent landed him the role and emphasized how unusual it was, in the early 1970s, to have a Black actor cast to voice a Black animated character. “How do you not applaud someone who knows the importance of casting a Black actor even though it’s just a voice?” he said.

It was, in its way, another quiet barrier being nudged aside.

The Thanksgiving Table Becomes a Flashpoint

For most of its broadcast life, A Charlie Brown Thanksgiving was regarded as one more cozy, jazz-scored holiday ritual — nothing more controversial than the question of whether popcorn counts as dinner. But in the age of social media, screenshots travel farther than context.

Beginning in the mid-2010s, viewers began circulating a still image from the special. In it, Franklin sits alone on one side of the makeshift table in that folding lawn chair, while four white characters sit facing him on sturdier, higher-backed chairs. Charlie Brown, notably, faces Franklin from the opposite side, but the frozen frame became a symbol of the ways Black characters are often visually isolated in largely white stories.

Commentators debated whether the shot revealed latent racism or unconscious bias. The Root took up the question in a satirical piece titled “Is Peanuts Racist? An Exclusive Interview With Franklin, Charlie Brown’s Black Friend,” using humor to probe the unease many Black viewers felt watching the scene.

Fact-checking site Snopes, which explored wider allegations of racism in Peanuts, noted that there is no evidence Schulz himself directed the seating arrangement. By the 1970s, he typically wrote the scripts but wasn’t heavily involved in animation layouts.

Jean Schulz, the cartoonist’s widow, has said the choice was made by animators and directors, not by her husband. She has argued that the special, taken as a whole, is about inclusion — Franklin is invited, he’s seated near the center of the group in several shots, and he joins the others in singing on the way to grandmother’s house. To read the entire special as racist based on one camera angle, she suggested, is to miss both the era and her husband’s track record of pushing for integration in the strip.

Others, including scholars who study media representation, counter that intent is only part of the story. A Black child sitting alone in a lawn chair while white friends occupy more comfortable seats resonates with generations of viewers who have known what it means to be invited in but not fully welcomed. To them, that single frame crystallizes a pattern: Black characters allowed into white narratives only on certain terms and at the margins.

The truth, as always, is untidy: Franklin exists because of a conscious effort to integrate a beloved white space — and yet his placement still exposes the blind spots of the era that created him.

How Franklin’s Story Kept Evolving

Over time, Franklin’s legacy grew in ways even Schulz couldn’t have anticipated.

Black cartoonist Robb Armstrong, creator of the syndicated strip JumpStart, became both a friend of Schulz’s and a steward of Franklin’s story. In the 1990s, Schulz asked Armstrong if he could give Franklin the surname “Armstrong” in a TV special; Armstrong called it a “tremendous honor.”

In 2015, NPR devoted a Weekend Edition segment to Franklin’s 50th anniversary, highlighting how unusual it had been to see a Black child in a mainstream comic strip in 1968 and revisiting the correspondence with Glickman that made it happen. Ebony, marking Franklin’s 47th “birthday,” interviewed Mar Mar Walker, the teen who voiced Franklin in The Peanuts Movie. He said it was “a real honor” to play a character who first appeared “during a really hard time in our nation’s history” and who now simply exists alongside his friends without the story being about “the whole Black vs. White thing.”

In Black-led outlets like The Atlanta Voice and Word In Black–affiliated papers, Franklin’s promotion to title character in the Apple TV+ special Snoopy Presents: Welcome Home, Franklin has been treated as more than nostalgia. It’s a chance to revisit a milestone of representation and ask what it means for a new generation of children — many of them watching on tablets their grandparents could never have imagined.

The special, released in February 2024, retells Franklin’s origin as the child of a military family moving to a new town, struggling to make friends, and ultimately bonding with Charlie Brown over a soap box derby. Critics have praised it for quietly addressing Franklin’s earlier marginalization and giving him what one Washington Post headline called “a better seat at the table.”

Visually, that’s literal. In the new special’s Thanksgiving-adjacent sequences, Franklin sits shoulder-to-shoulder with the rest of the gang at a checkered table, his chair indistinguishable from theirs — a deliberate echo and correction of the 1973 lawn-chair shot.

What Thanksgiving Meant in Schulz’s Hands

Schulz was never a polemicist. He famously insisted Peanuts was “just a comic strip” even as it tackled theology in A Charlie Brown Christmas, existential angst in everyday gags, and, through Franklin, racial integration.

In A Charlie Brown Thanksgiving, he approached the holiday obliquely. The story spends little time on Pilgrims or the Wampanoag people whose land forms the backdrop of the American Thanksgiving myth. Linus offers a brief, earnest grace recounting the first Thanksgiving; then the special pivots back to the messy present — to kids negotiating expectations, to improvised hospitality, to the idea that gratitude is less about a “proper” menu and more about who gathers around the table.

Franklin’s presence in that mix matters symbolically, even if the special never mentions race explicitly. In 1973, to see a Black child bow his head at the same table, sing the same song on the way to grandma’s condo, and share the same worries about homework and holidays was itself a quiet reimagining of who that national ritual was for.

But as critics from The Root to academic journals have noted, symbolism and structure don’t always line up. If the story expands the idea of who belongs at Thanksgiving, yet the framing still literally puts the Black child off to the side, viewers are right to interrogate that dissonance.

The People Behind Franklin’s Legacy

The history of Franklin is, at its core, a story about a chain of people who decided to do something slightly uncomfortable.

Harriet Glickman, the suburban teacher who risked a letter that might never have been answered. Her Black friends, who added their voices to persuade Schulz that a Black child in Peanuts wouldn’t be patronizing if he were allowed to be as fully drawn — and as flawed — as Lucy or Linus.

Charles Schulz, the Midwestern cartoonist who took seriously a stranger’s request, wrestled with his own doubts, and ultimately told powerful gatekeepers he’d rather walk away than draw a segregated classroom.

Robin Reed, the kid in a Hollywood recording booth in the early ’70s, whose very presence behind the microphone quietly countered a long history of white actors voicing Black characters.

Robb Armstrong, the Black cartoonist whose own work and partnership with the Schulz estate helped ensure Franklin’s story wouldn’t freeze in 1968 but keep evolving.

And now, directors, animators and writers — many of them people of color — who have taken up Franklin’s story and reframed that Thanksgiving table so that the visual grammar better matches the ideals the character has always represented.

A Seat at the Table, Then and Now

In the half-century since Franklin first picked up Charlie Brown’s beach ball, the strip that birthed him has ended, Schulz has died, and the Peanuts gang has migrated to streaming platforms and 4K restorations of their old specials. Yet the questions Franklin raises remain stubbornly contemporary.

Who gets drawn into our national stories — and who is left out of the frame? When we say everyone is welcome at the table, who actually gets a comfortable seat, and who is still balancing on the lawn chair at the edge?

Peanuts does not offer neat answers. But the path from Glickman’s letter to Franklin’s beach debut, from that awkward Thanksgiving screenshot to a new special that literally re-seats him in the center of things, traces the slow work of reimagining who belongs in American iconography.

For families who still press play on A Charlie Brown Thanksgiving each year, Franklin is more than a conversation-starter about one controversial shot. He is proof that even the most familiar stories can be revised, that audiences can demand better, and that a single child at a cartoon dinner table can, over time, nudge the real world a little closer to the one we say grace about.