40 Acres and a Mule

Sherman’s Order and the Birth—and Undoing—of Black Landownership

By KOLUMN Magazine

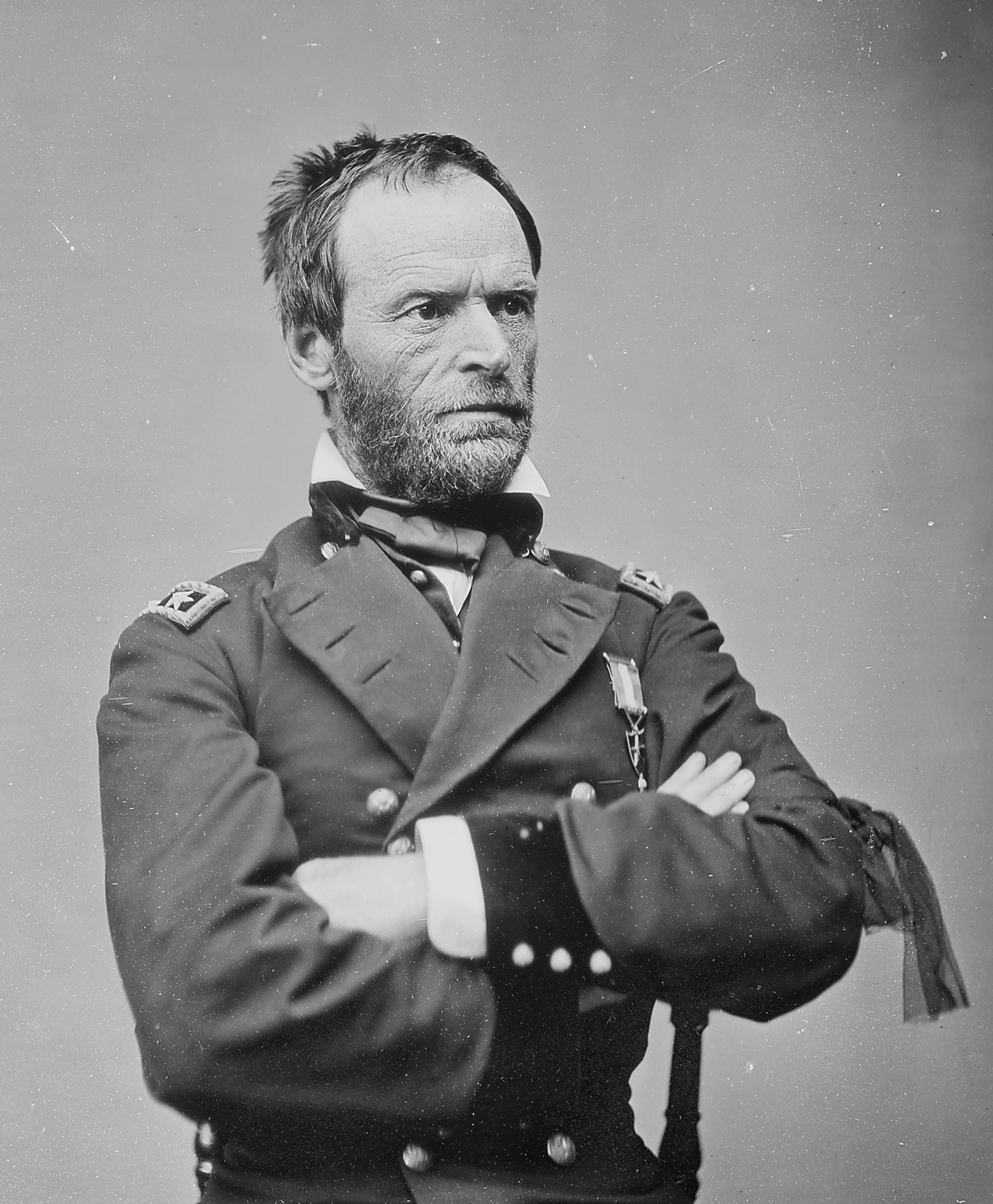

In January 1865, as Union troops occupied Savannah and the Confederacy staggered toward defeat, a group of 20 Black ministers and lay leaders filed into the parlor of a wealthy merchant’s home on Greene Square. They had been summoned to meet with Union General William Tecumseh Sherman and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton — and to answer one question: What do you want for your people?

Their spokesman, the 67-year-old Baptist minister Garrison Frazier, had purchased freedom for himself and his wife with $1,000 in gold. Now he spoke for thousands. Freedom, he said, required “land, and turn it and till it by our own labor.”

Four days later, on January 16, Sherman issued Special Field Orders No. 15 — a radical wartime directive that set aside a vast swath of the Southern coastline “for the settlement of the negroes now made free.”

Within months, roughly 40,000 formerly enslaved people had begun building lives on some 400,000 acres of what they called “Sherman land.” Within a year, most of that land would be taken back.

The story of Special Field Order No. 15 is often summarized in a shorthand phrase — “forty acres and a mule” — but the reality was more complex, and more devastating, than the slogan suggests. It is a story about maps and military orders, but also about families, bank books, and a shattered chance at generational wealth.

Drawing a new map of freedom

Sherman’s order was born of crisis as much as vision. His famous March to the Sea had left a trail of destruction — and a following of desperate people. Tens of thousands of enslaved men, women, and children had fled plantations to attach themselves to the Union army. They needed food, protection, and a future.

The January 12 meeting in Savannah brought that crisis into focus. The minutes of the gathering, published weeks later in the New York Daily Tribune, captured Frazier’s insistence that Black freedom required separation from white planters: “We want to be placed on land until we are able to buy it and make it our own.”

Sherman’s Special Field Orders No. 15, issued from Savannah four days later, did something unprecedented in U.S. history:

It confiscated a strip of Confederate coastal land — the Sea Islands and rice plantations from Charleston, South Carolina, down to the St. Johns River in Florida, and 30 miles inland — roughly 400,000 acres.

It reserved this land solely for Black settlement, explicitly barring most white people from living there.

It directed that the land be divided into plots of up to 40 acres for Black families who had been enslaved on those estates.

One key section laid out the promise that would echo across generations: each family “shall have a plot of not more than forty acres of tillable ground,” with military protection “until such time as they can protect themselves, or until Congress shall regulate their title.”

The order placed administration of this “Sherman Reserve” in the hands of General Rufus Saxton, an abolitionist officer who had already overseen early experiments in Black landholding on South Carolina’s Sea Islands.

What Sherman framed as a military necessity — a way to get thousands of refugees off his supply lines — many freedpeople recognized as something closer to justice.

How the land was allocated

Sherman’s order did not automatically hand over deeds. It created a framework for settlement first, legal title later. The details of allocation were worked out by Saxton and Freedmen’s Bureau agents on the ground.

From plantations to plots

In the spring of 1865, federal officials and army surveyors began the painstaking work of turning confiscated plantations into farms for former slaves:

Former plantation tracts were divided into parcels, which were often called “forty-acre lots” even when they varied widely in size — from 8 acres to more than 400, according to one contemporary observer.

Families applied for plots through Saxton’s office; many received certificates of possession, understood as preliminary proof that this land would soon be theirs.

On some islands — like Skidaway near Savannah — freedpeople organized collective settlements, pooling labor and resources. One such colony counted more than 1,000 residents under the leadership of the Rev. Ulysses L. Houston, one of the ministers at the Savannah meeting.

By June 1865, about 40,000 freedpeople were working and living on roughly 400,000 acres of coastal land, planting corn, sweet potatoes, and cotton, building cabins, schools, and churches.

“It was Plymouth colony repeating itself,” one Northern correspondent marveled, describing the Sea Islands as a Black New England — a self-governing republic rising from the ruins of slavery.

The Freedmen’s Bureau steps in

Just weeks after Sherman’s order, Congress created the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, better known as the Freedmen’s Bureau, giving it authority to manage confiscated and abandoned property and to lease or assign parcels of up to 40 acres to freedpeople.

Bureau Commissioner Oliver Otis Howard later issued Circular No. 13, instructing agents to “conserve forty-acre tracts of land for the freedmen.” At its peak in 1865, the bureau controlled between 800,000 and 900,000 acres of plantation land across the South.

In theory, freed families would lease the land for several years, paying modest rent, and eventually gain the right to purchase it outright.

On the Sea Islands, this layered architecture — Sherman’s order, Congress’s land provisions, and Bureau policies — created a sense that the land was not a temporary refuge but a down payment on belonging.

“We has a right to the land”

For the people farming “Sherman land,” allocation was not an abstract policy. It was a moral reckoning.

In a speech in Virginia in late 1866, a freedman named Bayley Wyat (sometimes spelled Wyatt) explained why he and his neighbors refused to surrender the land they were working:

“Our wives, our children, our husbands, has been sold over and over again to purchase the lands we now locates upon; for that reason we have a divine right to the land.”

The same conviction echoed in letters and reports collected by the Freedmen’s Bureau. One Northern missionary wrote home that Freedmen were “very eager for land,” using savings and cotton profits to make purchases wherever possible.

Those savings increasingly flowed into a new institution: the Freedman’s Savings and Trust Company, better known as the Freedman’s Bank. Chartered by Congress in March 1865 — the same day it formally created the Freedmen’s Bureau — the bank was meant to give formerly enslaved people a safe place to deposit wages from army service and plantation work.

When Black men and women opened accounts, they provided detailed personal information — names of spouses, children, parents, and siblings — leaving behind rich records of families who had survived slavery and who now imagined futures anchored in land and savings.

In many Sea Island communities, the same families who held certificates to forty acres also held passbooks at the Freedman’s Bank. The land allowed them to feed themselves; the bank, they hoped, would help them buy tools, rebuild houses, and one day secure full legal title.

In other words, they acted like small farmers and small savers do everywhere: treating both soil and savings accounts as building blocks for their children.

The counter-revolution: reclaiming the land

If Sherman’s order was the most radical act of wartime redistribution, President Andrew Johnson’s policies later in 1865 amounted to a counter-revolution in property.

Johnson’s amnesty and Circular No. 15

Just weeks after taking office following Lincoln’s assassination, Johnson issued a sweeping amnesty proclamation for most former Confederates. Pardoned landowners were encouraged to petition for the restoration of their property — including land now occupied by freedpeople under Sherman’s order.

Under pressure from the White House, General Howard rescinded his own land-redistribution directive and replaced it with Circular No. 15, instructing Bureau agents to return confiscated lands to pardoned owners, with one narrow exception: lands already sold or under cultivation by loyal freedpeople were not to be disturbed until crops were harvested or compensation paid.

On the Sea Islands, ex-Confederate planters descended on Saxton’s office with stacks of pardons in hand. Saxton, who believed the land should remain in Black hands, pleaded with Howard and Stanton to protect the settlers. Howard, dispatched by Johnson to broker a “mutually satisfactory” settlement, understood that the president expected full restoration of prewar ownership.

When Howard visited the islands that fall, he faced packed meetings of freedpeople who insisted they would not abandon land they had cleared and planted. Many had already built cabins and churches, buried loved ones in small graveyards, and harvested their first crops as free people.

Yet, case by case, plantations were signed back to their former owners. Freed families were told they could stay only as wage laborers or sharecroppers.

Eviction from “the promised land”

Free people did not give up quietly. In Virginia, Bayley Wyat addressed federal officers directly:

Despite such protests, historians estimate that almost all of the land confiscated under Sherman’s order and managed by the Freedmen’s Bureau was ultimately restored to white owners.

The impact was immediate and brutal. On the Sea Islands and across the South, Black families were pushed off “Sherman land” or forced into contracts that bound them to the same plantations where they had been enslaved — now paid in a share of the crop instead of in chains.

The Freedmen’s Bureau, which had briefly acted as a protector of Black land rights, was transformed into an agency that policed labor contracts and enforced a plantation wage system.

For formerly enslaved people, the message was unmistakable: even when they planted, built, and saved, the law and the state could still take everything back.

Bank books and broken promises

The collapse of land redistribution is inseparable from another institution born in 1865 — the Freedman’s Savings Bank — and from the intimate stories recorded in its ledgers.

By design, the bank was a cornerstone of Black economic citizenship. Its founders, including prominent white abolitionists, imagined it would teach thrift and offer safe savings to a people long denied both wages and ownership. Frederick Douglass, who later became the bank’s final president, praised its mission to show formerly enslaved people “how to rise in the world.”

The bank boomed. Branches opened near army camps, in Southern cities, and in port towns where Black soldiers and laborers received wages. By the early 1870s, more than 60,000 depositors had entrusted nearly $3 million — a staggering sum for families only recently freed.

Researchers who have examined the bank’s surviving records note that many depositors were agricultural workers and small farmers: people whose hopes were tied to both land and savings. One recent economic study argues that the bank aggressively marketed itself through churches and Freedmen’s Bureau offices, sometimes falsely implying that deposits were backed by the U.S. government.

When federal policy reversed Sherman’s land grants, those same families confronted a double loss:

The land they worked under Sherman’s order was restored to ex-Confederates.

Their savings, often intended to buy land elsewhere or survive lean years, were increasingly at risk in a poorly regulated bank.

In 1874, after years of mismanagement and risky investments by white trustees, the Freedman’s Bank collapsed. Depositors recovered only a fraction of their money, if anything at all.

One historian of the bank called the scale of depositor losses “rarely matched in U.S. banking history.”

The names in those ledgers — farmers, laundresses, carpenters, teachers — are the “bank customers” whose personal narratives shadow the story of Special Field Order No. 15. Taken together, they reveal a generation that tried to convert emancipation into land, savings, and security, only to see each pillar kicked away.

What might have been — and what remains

Economists and historians have tried to estimate what Sherman’s order, fully honored, might have meant. One analysis suggests that giving 40 acres and a mule to roughly 40,000 freed families could have created wealth worth hundreds of billions of dollars in today’s terms.

Instead, freedpeople were largely denied both land and reliable financial institutions, while white Americans benefited from massive federal land giveaways under the Homestead Act and other policies.

The result is visible in the enduring racial wealth gap. As historian Henry Louis Gates Jr. has written, Sherman’s order represented the first systematic attempt at reparations — the federal confiscation and redistribution of private property to former slaves — and its reversal marked a decisive turning point.

Yet the memory of Special Field Order No. 15 has not vanished. In Savannah, a historical marker in Madison Square — just steps from the house where Sherman met those Black ministers — tells passersby about the order that once reserved coastal land for freed families in forty-acre tracts, and about the president who revoked it.

In Congress, the modern reparations bill H.R. 40 takes its number from the unfulfilled promise of “forty acres and a mule.”

And in archives, the fragile paper trail of that moment endures:

Certificates of possession issued on Sea Island plantations.

Freedmen’s Bureau reports documenting protests against eviction.

Bank registers listing the signatures of depositors whose savings never returned.

These are more than bureaucratic relics. They are the fingerprints of a generation that believed, with reason, that the United States government had finally recognized their “divine right to the land” they had worked for centuries.

Special Field Order No. 15 lasted barely a year. But its brief life — and its long afterlife in bank ledgers, family stories, and political demands — continues to frame a central question of American democracy:

What does freedom mean if those who were once treated as property are never allowed to own property of their own?