Proceed and Be Bold:

Amos Paul Kennedy Jr. Rewrites the Rules of Who Art Is For

By KOLUMN Magazine

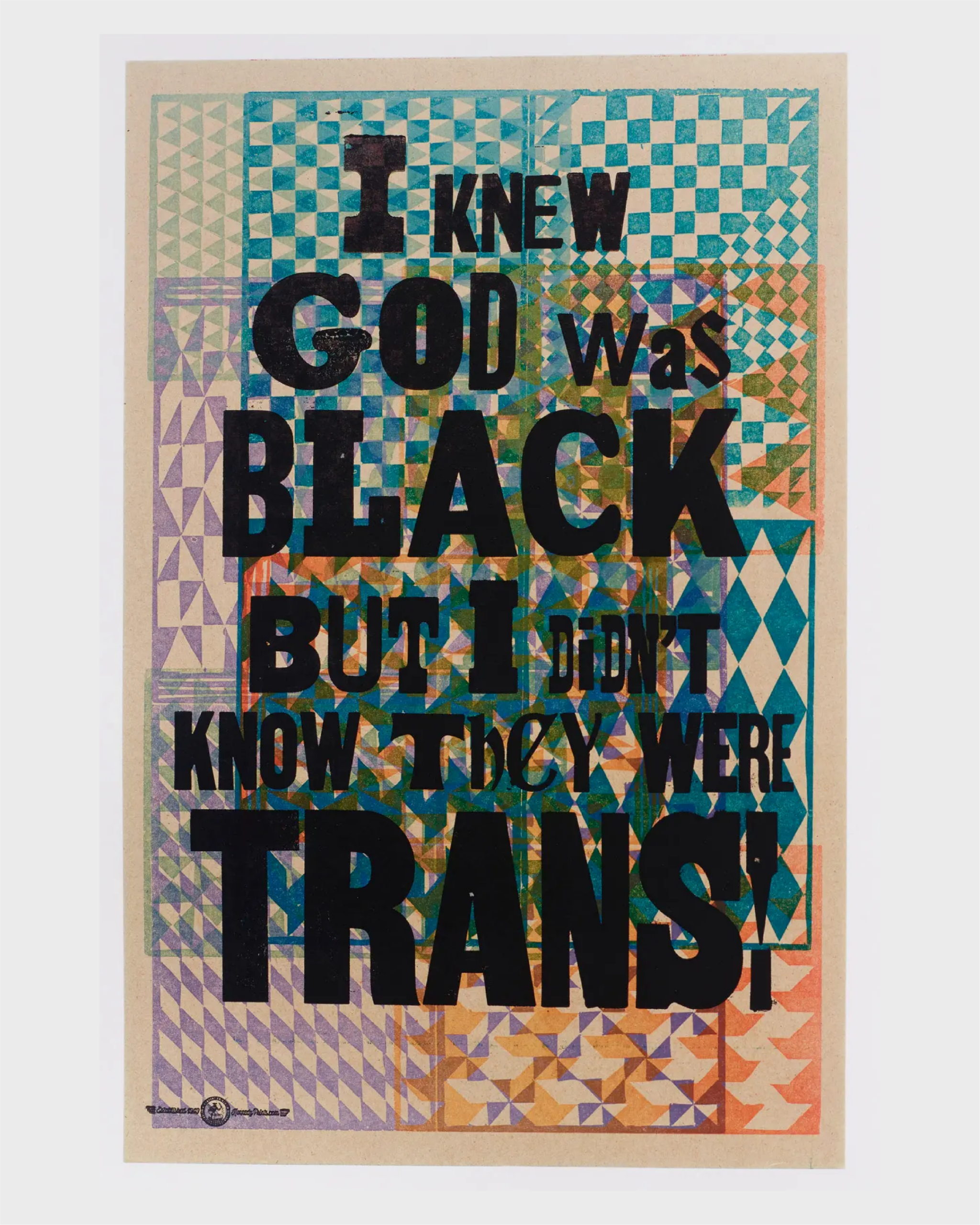

On a cold morning in Detroit, the warehouse doors of Kennedy Prints open with a rattle and a scrape. Inside, the air is thick with oil-based ink and the metallic clank of type. Stacks of posters lean in uneven columns against the walls: brilliant oranges, searing magentas, deep indigos, all shouting fragments of language — RACISM IS STILL WITH US, YOU MUST NEVER BE FEARFUL ABOUT WHAT YOU ARE DOING WHEN IT IS RIGHT, RISE FOR CLIMATE, JOBS AND JUSTICE.

The man at the center of this riot of color moves slowly, deliberately. In inky overalls, with hands stained the permanent blue-black of his trade, Amos Paul Kennedy Jr. sets another line of wood type into a chase. He calls himself, pointedly, a “humble negro printer,” not an artist — a phrase he’s repeated for years as both jab and joke at an art world that too often reserves seriousness for white, elite spaces.

Outside, his posters might be taped in a corner store window, pinned to a community bulletin board, or framed in a museum, sharing a wall with canonical works that helped define Western art history. Inside, they are tools — declarations, in his words — churned out not for scarcity and speculation, but for circulation.

“Printing,” Kennedy likes to say, “allows for declarations to be distributed to the masses. Declarations are about the redistribution of power.”

That belief — that ink, paper, and a hand-cranked press can be instruments of democracy — has propelled Kennedy’s unlikely trajectory from corporate systems analyst to one of the most distinctive and quietly influential printmakers in contemporary American art.

From AT&T to the Print Shop

Kennedy was born in Lafayette, Louisiana, in the late 1940s, and came of age in the shadow of the Civil Rights Movement and the rise of Black Nationalism. He studied mathematics at Grambling State University, graduating in 1972, and built a steady career as a systems analyst at AT&T — the embodiment of Black middle-class success in a still-segregated America.

Then, at 40, he stepped into a different century.

During a family vacation to Colonial Williamsburg, Kennedy wandered into an 18th-century print shop demonstration. Within minutes, he was mesmerized by the dance of type and paper. In later interviews, he has described that moment with analytical precision: what gripped him was the capability of making multiples — printing the same words, over and over, until they could travel far beyond the confines of any single room.

Back home, he found a community letterpress shop in Chicago, began to study printing, and — within a year — quit his well-paying corporate job to pursue printmaking full time.

He went back to school, enrolling in the University of Wisconsin–Madison’s storied book arts program. There he studied under the legendary book designer and printer Walter Hamady, earning an MFA in 1997. Teaching followed: a position in graphic design at Indiana University Bloomington, where he passed on his evolving philosophy of printing as a democratic practice.

But academia, like the corporate world, has its rules. Kennedy preferred the freedom of the pressroom to the politics of faculty meetings. Over the years he moved his shop — first outside Chicago, then to Wisconsin, then to rural Alabama — before eventually landing in Detroit, where Kennedy Prints now operates out of an industrial building that doubles as a community hub.

A “Humble Negro Printer” in an Elite Art World

By conventional art-world standards, Kennedy’s approach borders on heresy.

He prints on inexpensive chipboard, not fine cotton rag paper. He uses salvaged wood and metal type. His editions are large, often in the hundreds, and he undercuts the aura of uniqueness — that engine of high prices — by overprinting, layering, and improvising until no two posters are quite the same.

The work is defiantly accessible. At community events, his posters might sell for $10 or $20, a price that puts them within reach of students, librarians, activists, and parents who might never expect to own “art” at all. Online, small-scale collaborations show his prints marketed as affordable, hand-printed pieces that sit comfortably in a kitchen or a child’s bedroom.

The words, however, are anything but gentle.

A typical Kennedy poster is a layered field of color — a base of orange and yellow, perhaps, overprinted with red shapes and ghosted type — topped with a blunt phrase in heavy black letters. They might quote Fannie Lou Hamer, Frederick Douglass, or Sojourner Truth; they might advertise a small-town okra festival, a poetry reading, or a church revival. Within the same stack you might find a command to KNOW JUSTICE KNOW PEACE or a reminder that RACISM IS STILL WITH US, BUT IT IS UP TO US TO PREPARE OUR CHILDREN FOR WHAT THEY HAVE TO MEET.

In the 2024 monograph Citizen Printer, published by Letterform Archive, writers describe him as both a “poet and printer” and “a major historian and theorist of print as democratic art.” The book reproduces more than 800 of his works, organized into chapters on social justice, shared wisdom, and community — a structure that mirrors how the posters move through the world.

The self-styled “humble negro printer” is, in other words, anything but marginal.

His work is held in the collections of the Library of Congress, the Museum of Modern Art’s library, Poster House in New York, the Bainbridge Island Museum of Art, and numerous university and public libraries. He has received a major United States Artists fellowship in crafts and has been recognized by the American Printing History Association and the Mid America Print Council for his contributions to printmaking.

Yet Kennedy continues to insist that the art is not the individual poster itself, priced and framed, but the wall they make together — a dense grid of language and color that envelops the viewer and, ideally, invites participation.

One upcoming exhibition is even titled “The Art is on the Wall, Not on the Posters,” a kind of manifesto masquerading as a show announcement.

The Rosa Parks Series: Multiples as Memory Work

If one body of work captures Kennedy’s ethos, it is his decade-spanning Rosa Parks series.

Shortly after Parks’ death in 2005, Kennedy began creating posters centered on her words. The resulting series — dozens of prints, each layering type and color in different configurations — seeks to rescue Parks from the flattening narrative of a tired seamstress on a bus and restore her to the breadth of her lifelong activism.

Kennedy’s Rosa Parks prints are now in the collections of the Library of Congress and have been exhibited widely, including a 2022–23 show at the Bainbridge Island Museum of Art in Washington state. That exhibition borrowed 16 Parks posters from the personal collection of patron and museum founder Cynthia Sears, who has quietly assembled a substantial archive of his work.

The prints layer Parks’ statements — “I WAS JUST TRYING TO LET THEM KNOW HOW I FELT ABOUT BEING TREATED AS A HUMAN BEING,” “YOU MUST NEVER BE FEARFUL ABOUT WHAT YOU ARE DOING WHEN IT IS RIGHT” — over fields of overlapping words like MONTGOMERY, SEGREGATION, CITY CODE, CLEVELAND AVE.

Visually, they’re loud: bright reds and yellows, stenciled shapes, shadowed letters that tumble out of alignment. Conceptually, they function as memory work. Instead of a single definitive commemorative image — the iconic photograph, the solemn statue — Parks’ voice appears as a series of variations, each shot through with new information, new resonances.

For viewers, especially Black viewers who encounter these prints outside traditional museum settings, the experience can be intimate. A Rosa Parks poster pinned above a library circulation desk or hung in a school hallway does not demand reverent distance; it leans into daily life, a constant reminder that civil rights history is not fixed but still unfolding.

In this way, Kennedy’s multiples operate like community-owned monuments, scattered across living rooms, classrooms, churches, and storefronts — each one a small declaration that history belongs to the people who live with it.

“Pull-a-Print”: Community as Co-Creator

While his posters circulate widely, Kennedy is perhaps most animated when the printing process itself is shared.

At “Pull-a-Print” events held at libraries, art centers, and book-arts studios across the United States, he invites people — children, students, elders — to step behind the press, ink the form, and crank the handle themselves.

These workshops are deceptively simple. Participants choose from handset type and pre-arranged forms that carry aphorisms, proverbs, or quotes from civil rights leaders. Kennedy hovers nearby, cracking jokes, sliding a new sheet of chipboard into place, urging them to lean their weight into the pull.

The result is a stack of posters that are technically his — built from his type, his forms, his inks — but also theirs: uneven ink coverage, off-kilter registration, and the occasional smudge becoming evidence of many hands at work.

In one university residency, described in a campus profile, Kennedy filled a gallery’s walls with hundreds of small chipboard cards printed with “the wisdom of the communities” — sayings that had circulated among workshop participants and were then set in metal type and printed in multiples.

This is where Kennedy’s insistence that printing is “a very democratic process” comes into focus. The posters are not meant to be pristine objects; they are evidence of a process that the public can join.

For librarians and art educators, this has particular power. In a field where a landmark study showed that 85 percent of artists in major U.S. museum collections are white and 87 percent are men, Black children and other students of color rarely see themselves reflected in the canon on the walls.

Kennedy’s presence — a Black printer, running a press with words from Black activists and everyday sayings from Black communities — effectively redraws the frame. Art is no longer something made elsewhere, by someone else; it is under their hands, right now, on a sheet of chipboard they can take home.

Everyday Patrons, Not Just Collectors

Critical writing about Kennedy often focuses on his relationship to museums and design history — the way his work riffs on 19th-century broadsides, for instance, or sits in dialogue with the legacy of Black printing in America.

But to understand his impact, it’s equally important to look at the people who actually live with his posters.

At a small independent bookstore outside Detroit, a recent event celebrated the release of Citizen Printer with a signing and pop-up sale. The shop’s announcement highlighted Kennedy’s “type-driven messages of social justice and Black power” and drew regular customers, young local artists, and older residents who remembered Detroit’s uprisings and deindustrialization.

Some came for the book; many came for the posters. A retiree left with a print about voting rights; a high-school art teacher picked up a Rosa Parks piece and a poster exhorting students to READ MORE BOOKS for her classroom; a social worker chose one about preparing children to confront racism, intending to hang it in a community center.

At a public library in the Pacific Northwest, staff added Kennedy prints to their permanent art collection — bold, typographic pieces they described in a blog post as “words to live by, or at least think about.” The posters hang not in a guarded gallery but in reading rooms and corridors, where patrons pause to read them on the way to the stacks.

In Bainbridge Island, the Rosa Parks series that collector Cynthia Sears acquired has been shown not as a distant treasure but in a free museum whose mission explicitly centers community access and education.

For these patrons — teachers, librarians, retired factory workers, college students furnishing cramped apartments — Kennedy is less a distant art-world figure than a kind of neighborhood sign painter of the Black radical tradition. His posters enter their lives where big ideas usually don’t: above the kitchen table, near the school office, on the corkboard of a union hall.

They are, in effect, everyday literacy tools, asking their owners and everyone who walks past to read, think, and argue with the language they carry.

Humor, Agitation, and Living Debt-Free

Kennedy’s work is often described as “joyful agitation,” a phrase that captures the mix of humor and seriousness that defines his public persona.

In a 2020 interview with the art journal Glasstire, conducted against the backdrop of Black Lives Matter protests, Kennedy spoke about the importance of humor in his art and life. Jokes, he suggested, are not a distraction from political critique but a way to sustain it — a method for enduring and resisting in a society that relentlessly devalues Black life.

He has also been candid about money. One of the quiet subtexts of his story — a midlife reinvention from secure corporate job to precarious art practice — is debt. Kennedy has spoken about choosing to live debt-free, structuring his life and work around the practical demands of paying his monthly bills rather than chasing speculative art-world validation.

That stance shapes everything from his materials (cheap chipboard and salvaged ink) to his sales model (low prices, high volumes, direct relationships with buyers). It also connects to a longer history of Black mutual aid and economic self-determination, where community resources are stretched through collective effort and creative reuse.

In this sense, Kennedy’s posters are not only visual interventions; they are economic ones. By refusing to make scarcity the measure of value, he undermines the logic that keeps so much art — and by extension, so much cultural power — locked in private collections and inaccessible institutions.

A Career in Retrospect — and in Motion

If Citizen Printer has the feeling of a retrospective, it is one that refuses to mark an ending. The book’s publication in 2024 coincided with a major exhibition at Letterform Archive in San Francisco, running through early 2025, that immerses visitors in walls of Kennedy’s posters grouped by theme: abolition, food justice, Black history, protest, community.

Other exhibitions, like the Institute for Contemporary Art at Virginia Commonwealth University’s “Declaration” and the forthcoming “The Art is on the Wall, Not on the Posters” in Ohio, continue to test the boundaries between installation, archive, and public forum.

Meanwhile, Kennedy is still on the road. He leads workshops at book-arts centers, visits universities as a printer-in-residence, and sets up makeshift printshops at community events. Partners in Print, a Seattle-based organization, describes him simply: “born 1950 … working a corporate job for AT&T when, at the age of 40, he discovered the art of letterpress printing … [and is now] internationally recognized for his type-driven messages of social justice and Black power.”

The recognition matters — especially in a museum landscape where, as that landmark 2019 study revealed, artists of color remain drastically underrepresented. But Kennedy’s own measure of success appears to be more modest and more radical at once.

He wants his prints to be everywhere.

On the way out of his Detroit shop, visitors often leave with more posters than they intended to buy. A slogan about public schools for a niece who teaches third grade. A Rosa Parks quote for a cousin in Birmingham. A poster about food deserts for a community garden back home.

Each one leaves the warehouse and enters another circulation — pinned to a wall, taped to a window, photographed and shared online, glimpsed by a stranger, remembered later in a different context.

Ink, Paper, and the Question of Who Gets to Speak

There is an old idea in American political life that pamphlets and broadsides — cheap printed matter — can alter the course of history. Abolitionist handbills, union leaflets, and civil rights flyers all relied on the stubborn clarity of ink on paper.

Amos Paul Kennedy Jr. stands firmly in that lineage, but he insists that the work is not only to print about justice; it is to print in ways that redistribute who gets to speak and who gets to own the language of resistance.

That’s why his posters rarely appear alone. They demand company — other posters, other voices, other hands cranking the press.

In an art system still grappling with the fact that its collections are overwhelmingly white and male, the sight of Kennedy’s chipped, overprinted, unpretentious posters in a major museum can feel like an anomaly. But in a school hallway, a storefront church, a union office, or a public library, they feel right at home.

The power of his work lies there, in those ordinary rooms: a teenager pausing to read a line from Rosa Parks between classes; a parent noticing a poster about racism at a PTA meeting; a library patron taking home a visual reminder that justice is not abstract but personal.

Each poster is a small, portable declaration. Together, they form something closer to what Kennedy has spent the last three decades building — a living, breathing wall of language, ink, and collective memory that quietly asks, every time you read it:

What will you do with these words now?