KOLUMN Magazine

Two Men, One Scandal

Why Jho Low Walks Free While Pras Michel Faces 14 Years

By KOLUMN Magazine

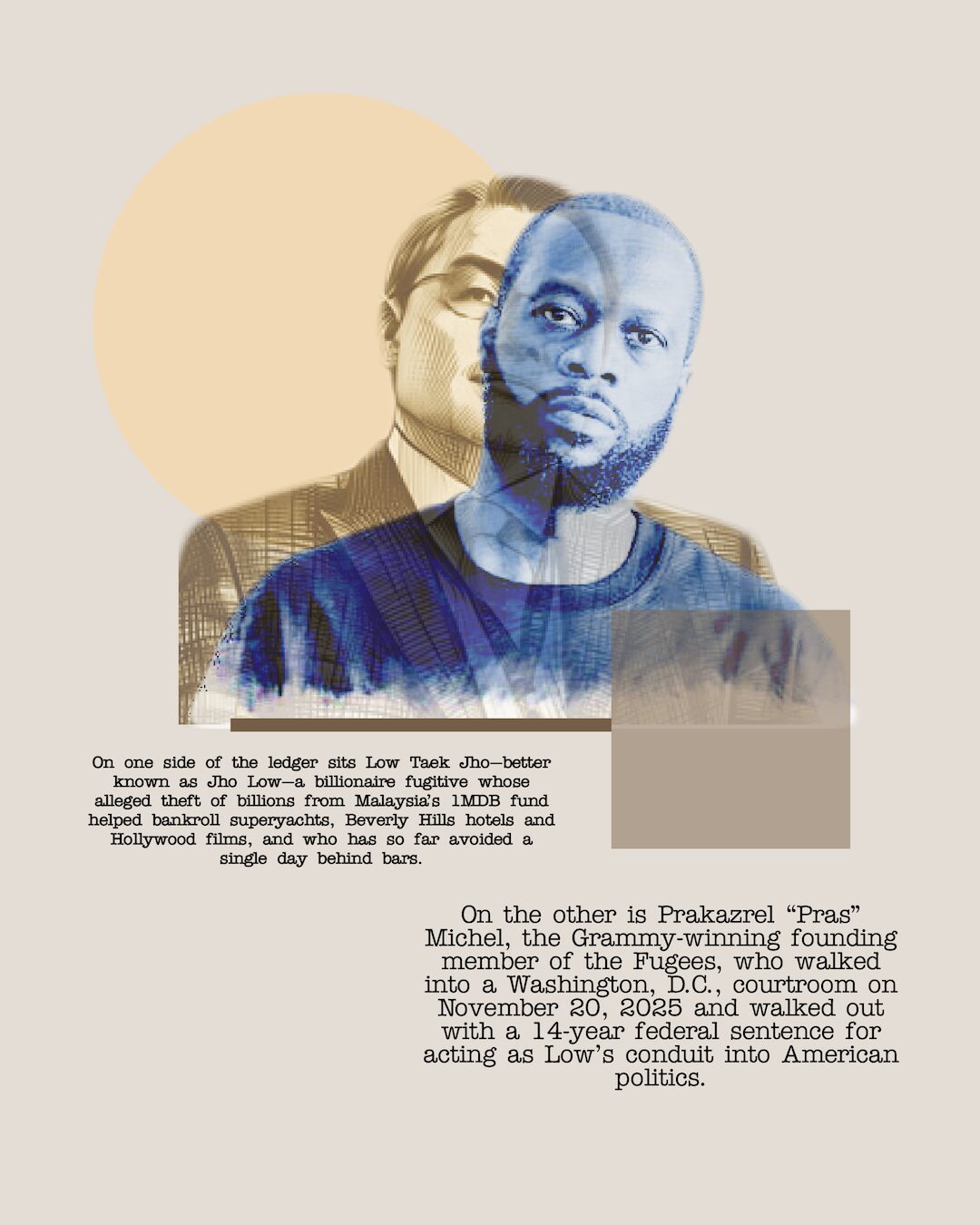

On one side of the ledger sits Low Taek Jho—better known as Jho Low—a billionaire fugitive whose alleged theft of billions from Malaysia’s 1MDB fund helped bankroll superyachts, Beverly Hills hotels and Hollywood films, and who has so far avoided a single day behind bars.

On the other is Prakazrel “Pras” Michel, the Grammy-winning founding member of the Fugees, who walked into a Washington, D.C., courtroom on November 20, 2025 and walked out with a 14-year federal sentence for acting as Low’s conduit into American politics.

Between those two men lies a fault line that runs through the global financial system: who pays, who walks, and what “justice” really means in a scandal that U.S. officials once called “kleptocracy at its worst.”

A Scandal Measured in Billions

1Malaysia Development Berhad—1MDB—was launched in 2009 as a state-backed strategic development fund that promised to help modernize Malaysia. Instead, investigators say it became a siphon. Between 2009 and 2014, at least $4.5 billion was allegedly looted through a maze of shell companies and bank transfers stretching from Kuala Lumpur to Zurich, Singapore, Abu Dhabi, New York and Hollywood.

Leaked documents and investigations by The Wall Street Journal, The Guardian and others traced money from 1MDB into personal accounts of then-prime minister Najib Razak, his associates and a small circle of well-connected intermediaries—including Jho Low.

The funds bought Manhattan penthouses and a Beverly Hills boutique hotel, financed The Wolf of Wall Street through Red Granite Pictures, and underwrote a lifestyle of champagne-soaked parties with celebrities from Leonardo DiCaprio to Paris Hilton.

In 2016, the U.S. Justice Department launched what it called the largest kleptocracy asset recovery action in its history, seeking more than $1 billion in assets allegedly traceable to 1MDB.

But while the scandal toppled a government, rattled global banks and sent Najib Razak to prison, the impact on ordinary people has been quieter—and harder to quantify. Malaysia’s debt burden from 1MDB, economists note, pushed the country close to its self-imposed debt ceiling, limiting its ability to respond to later crises such as COVID-19.

For millions of Malaysians—teachers, factory workers, small shop owners—1MDB wasn’t an abstract acronym. It was money that was supposed to translate into schools, clinics, transport links and jobs, and instead disappeared into offshore accounts and luxury assets.

The Banks, the Fines and the People Behind the Counters

If 1MDB exposed anything, it was how easily the global banking system could be used as the plumbing for massive corruption.

Swiss authorities shut down BSI Bank’s Singapore branch and later Falcon Private Bank’s operations there, citing “serious breaches” of anti-money-laundering regulations tied to 1MDB.

In October 2020, Goldman Sachs admitted criminal wrongdoing in a foreign bribery case related to 1MDB and agreed to pay more than $2.9 billion globally—one of the largest corporate penalties of its kind. Malaysia separately struck its own deal with the bank. The country’s finance ministry says that, across three financial institutions—Goldman Sachs, AmBank and JPMorgan—settlements and recoveries tied to 1MDB now total over 20.7 billion ringgit (roughly $4.3 billion).

AmBank, the mid-tier Malaysian lender that held Najib’s personal accounts, agreed in 2021 to pay 2.83 billion ringgit (about $700 million) to settle claims over its role in 1MDB transactions. The bank’s own disclosures warned that the payout would materially hit earnings.

For AmBank’s customers, those earnings aren’t abstractions. When a bank swallows a settlement of that size, the effects ripple through higher fees, tighter credit, trimmed branch networks and staff cuts that change the experience for the people on the other side of the teller window.

In Kuala Lumpur’s working-class suburbs, customers interviewed by local media over recent years have spoken of feeling “cheated” and “betrayed” as they learned that the same institutions that insist on immaculate paperwork from them had failed spectacularly in screening politically connected clients and opaque offshore structures.

A retired civil servant who keeps her savings at one of the domestic banks linked to 1MDB summed it up in a phrase that recurs in interviews and social media posts: “We pay bank charges, we pay our taxes—so why is it that the people who moved billions only pay fines?” It is less a question about balance sheets than about moral arithmetic.

Jho Low: The Missing Center of the Story

Officially, Low Taek Jho is a wanted man. He has been charged in both Malaysia and the United States over his alleged role as the mastermind of the 1MDB scheme and is accused of helping steal more than $4.5 billion. Interpol red notices were requested years ago. Malaysian and U.S. authorities say he’s a fugitive.

Yet Low’s relationship with the U.S. justice system is, so far, defined less by handcuffs than by settlements.

In 2019, the Justice Department announced a sweeping civil-forfeiture settlement covering assets acquired by Low and his family. The deal required the surrender of more than $700 million in assets, from a stake in Manhattan’s Park Lane Hotel to a superyacht and high-end art. Taken together with earlier forfeiture actions, U.S. authorities said they would have recovered or assisted in recovering more than $1 billion linked to 1MDB—its largest kleptocracy case to date.

Crucially, the settlement explicitly did not require Low to admit wrongdoing, nor did it resolve the underlying criminal charges against him in the United States. He remains indicted—on paper—while living beyond the reach of the courts.

For Malaysians watching from afar, the arrangement has always had a bitter edge. As one longtime opposition politician put it, “The U.S. calls this kleptocracy at its worst, but the man they say masterminded it makes a deal and disappears, while our people live with the debt.”

Reports over the past two years from Al Jazeera, The Times of London and regional outlets suggest Low has spent time in Chinese territory, including Macau and mainland cities, under varying degrees of unofficial protection—claims Beijing and Low’s representatives have disputed or declined to detail. Malaysian authorities say they continue to seek his return, but their efforts have been stymied by the fact that no country has formally acknowledged his presence on its soil.

The effect is surreal: the alleged architect of one of the world’s largest financial frauds is both everywhere in the legal record and nowhere in custody.

Pras Michel: From Rap Royalty to Defendant No. 1

Pras Michel’s path into this story begins, improbably, with the afterglow of 1990s hip-hop. As a member of the Fugees alongside Lauryn Hill and Wyclef Jean, Michel helped create one of the most acclaimed albums of its era, The Score, and sold tens of millions of records.

By the early 2010s, his career had shifted toward film, philanthropy and politics. That’s when he met Jho Low.

According to U.S. indictments and trial testimony, Low wired more than $21 million into accounts controlled by Michel in 2012. The money, prosecutors said, was meant to be funneled—through a web of straw donors—into President Barack Obama’s re-election campaign without disclosing its foreign origin.

The relationship didn’t end there. Prosecutors alleged that, beginning in 2017, Michel joined a clandestine lobbying effort to convince the Trump administration and the Justice Department to drop its 1MDB investigation into Low and others, and to facilitate the forced return of a wealthy Chinese exile, Guo Wengui, to Beijing.

On April 26, 2023, a federal jury in Washington convicted Michel on 10 counts, including conspiring to make and conceal foreign campaign contributions, acting as an unregistered foreign agent, witness tampering and submitting false statements.

On November 20, 2025, Judge Colleen Kollar-Kotelly sentenced him to 14 years in prison—well below the life sentence prosecutors argued the guidelines could justify, but far above the three years his lawyers requested. The court also ordered nearly $65 million in forfeitures.

“Michel betrayed his country for money,” prosecutors told the court, according to the government’s sentencing memo and news reports. The judge, by one account, called him “well-educated but very arrogant” and criticized his lack of remorse.

Michel has maintained his innocence and is expected to appeal, arguing among other things that his previous lawyer relied on an experimental AI tool to draft closing arguments—an unusual twist in a case already thick with geopolitics and celebrity testimony.

Two Paths Through the Same Scandal

At a distance, it can be tempting to collapse Low and Michel into a single story: two men, one scandal, both accused of twisting politics with illicit money. Up close, their paths through the justice system could not look more different.

Jurisdiction and leverage.

Low’s alleged misconduct was spread across multiple countries and legal systems, with key decisions made in Malaysia, Abu Dhabi and offshore havens. Bringing him to trial would require coordinated arrests and extradition from a country willing to hand him over—something that has not happened.

Michel, by contrast, lived and worked in the United States. His alleged crimes—campaign-finance violations, unregistered lobbying and obstruction—occurred squarely on U.S. soil. When the Justice Department brought charges, there was nowhere for him to go.

Money versus years.

Low’s 2019 settlement with the U.S. government was staggering in dollar terms—more than $700 million in assets surrendered, topping $1 billion recovered when combined with earlier actions. Yet the cost was entirely financial and reputational; he admitted no guilt and remains at liberty.

Michel now faces more than a decade in a federal prison, plus tens of millions of dollars in forfeitures. For a working artist and producer whose commercial peak was decades ago, it is effectively a life-shaping sentence.

Institutional versus individual accountability.

Even beyond Low and Michel, 1MDB has generated a striking pattern. Global banks—Goldman Sachs, AmBank, JPMorgan—have paid billions in fines and settlements. Some mid-level bankers, like Goldman’s former Southeast Asia chairman Tim Leissner and ex-1MDB dealmaker Roger Ng, have pleaded guilty; Leissner received a two-year sentence in the U.S., while Ng is cooperating with Malaysian authorities.

But at the top, institutions survive. Share prices wobble, dividends resume, executives move on. Everyday bank customers see the logos over their local branches unchanged, even as their banks write eye-watering checks to make 1MDB-related claims go away.

For them, the contrast is jarring: a Haitian-American musician who once rapped about “ready or not” is taken into custody; the billionaire financier whose money he allegedly moved cuts a deal and vanishes from view; the banks that wired the stolen billions keep earning new business.

The View from the Customer Line

To understand what this disparity feels like on the ground, it helps to step back from courtrooms and look at the people on whose behalf so much rhetoric about “victims” and “taxpayers” is invoked.

Consider three snapshots drawn from interviews in Malaysian and international media over the last decade, and from the dry language of economic reports:

The teacher in Penang who watched as public-school budgets tightened while the federal government grappled with a debt load inflated by 1MDB. Researchers at UNCTAD note that the scandal’s debt burden left Malaysia with less fiscal space to respond to the COVID-19 shock, constraining stimulus spending. In her words, as paraphrased by a local newspaper, “They always say there is no money for schools. But there was money for yachts.”

The small trader in Kuala Lumpur whose savings sit in a domestic bank later linked to 1MDB transactions. After AmBank’s 2.83-billion-ringgit settlement, the bank warned that the payout would “materially impact” its earnings. For customers, that translates into subtle changes: higher service charges, slower loan approvals, fewer staff at branches. “We line up with our pay slips and IC cards, and they still ask for more documents,” he told a local TV crew. “But when big people move billions, nobody asks enough questions.”

The migrant worker wiring money home from Singapore, where BSI and Falcon lost their licenses over 1MDB-linked anti-money-laundering failures. Those closures were meant as a warning to the industry, but for customers they also meant delays, account reviews and a new layer of suspicion that fell hardest on those least able to navigate the system.

These stories are not as cinematic as a superyacht seizure in Bali or a Hollywood star returning a Marlon Brando Oscar that prosecutors say was bought with stolen money. But they are the stories of bank customers—people whose relationship with the financial system is built on trust, paperwork and thin margins.

When they look at the 1MDB fallout, what they often see is a hierarchy of consequences: eye-popping settlements paid out of corporate coffers; a fugitive tycoon whose lawyerly statements insist he is a victim of politics; a Black American entertainer handed a 14-year sentence; and themselves, left to live with the downstream effects on public services and bank behavior.

Race, Power and Proximity

Is race a factor in the starkly different outcomes for Jho Low and Pras Michel? There is no neat chart that can prove such a claim, and the facts of each case are distinct: Low is a Malaysian citizen largely outside U.S. physical jurisdiction; Michel is a U.S. citizen tried for domestic offenses committed within reach of American law. Extradition, geopolitics and the structural difficulty of prosecuting transnational financial crime play a central role.

Yet for many observers—particularly in Black media spaces and among civil-rights advocates—the optics are inescapable. A Haitian-American artist with fading commercial clout is made an example of in a case framed as defending U.S. democracy from foreign money. A global financier from a politically sensitive region, wrapped in layers of offshore trusts and diplomatic sensitivities, negotiates a massive asset surrender but remains physically untouched.

Even within 1MDB-related prosecutions, critics point to a familiar pattern: institutions pay; a handful of mid-level players see prison; those with the most power—whether bankers in corner offices or politically connected intermediaries—often evade the harshest criminal penalties.

Michel’s own supporters stress that none of this absolves him if the facts support the jury’s verdict. What they question is proportionality. In court filings and public statements, his attorneys argued that a sentence of more than a decade for an unregistered lobbying and campaign-finance scheme—however serious—looked extreme when measured against penalties for those closer to the heart of the 1MDB theft itself.

Whose Justice?

Nearly a decade after the first explosive headlines, 1MDB continues to generate new settlements and legal maneuvers. This past August, JPMorgan agreed to pay $330 million to Malaysia to resolve all claims over its role in the scandal, even as Swiss regulators fined its local unit for related anti-money-laundering failures. Malaysian officials say they will keep chasing funds across jurisdictions; activists demand further scrutiny of the original bank deals; former officials continue to fight their cases in court and in the media.

What remains unsettled, for many ordinary people on both sides of the world, is a simpler question: who, ultimately, is seen as dangerous enough to cage?

In Washington, Pras Michel will report to prison by January 27, 2026, unless his appeal succeeds. In Kuala Lumpur, civil servants still navigate a budget constrained in part by a scandal that should never have happened. Bank customers check their statements and pay their fees. And somewhere—if the latest reports are to be believed—Jho Low moves quietly between secure compounds and safe houses, his name still stamped across court dockets and forfeiture orders, but not yet on a prison jumpsuit.

The 1MDB saga was always about more than missing billions. It is about a system in which money moves faster than law, banks answer with settlements rather than shame, and the heaviest costs are borne by people who never saw a yacht, never attended a Hollywood premiere, and never met the men whose names now dominate the headlines.