Oscar Micheaux

THE RELENTLESS FILMMAKER

Who Built a Black Cinema Revolution

By KOLUMN Magazine

Oscar Micheaux liked to tell people he was a pioneer before he was ever a filmmaker. Long before he picked up a camera, he was a Pullman porter riding the rails out of Chicago, a homesteader farming unforgiving South Dakota soil, a self-published novelist going door-to-door to sell his work to Black readers who rarely saw themselves in print. Each chapter of that life would become raw material for the movies that later made him, in the words of film historian Jacqueline Stewart, “the most important Black filmmaker who ever lived. Period.”

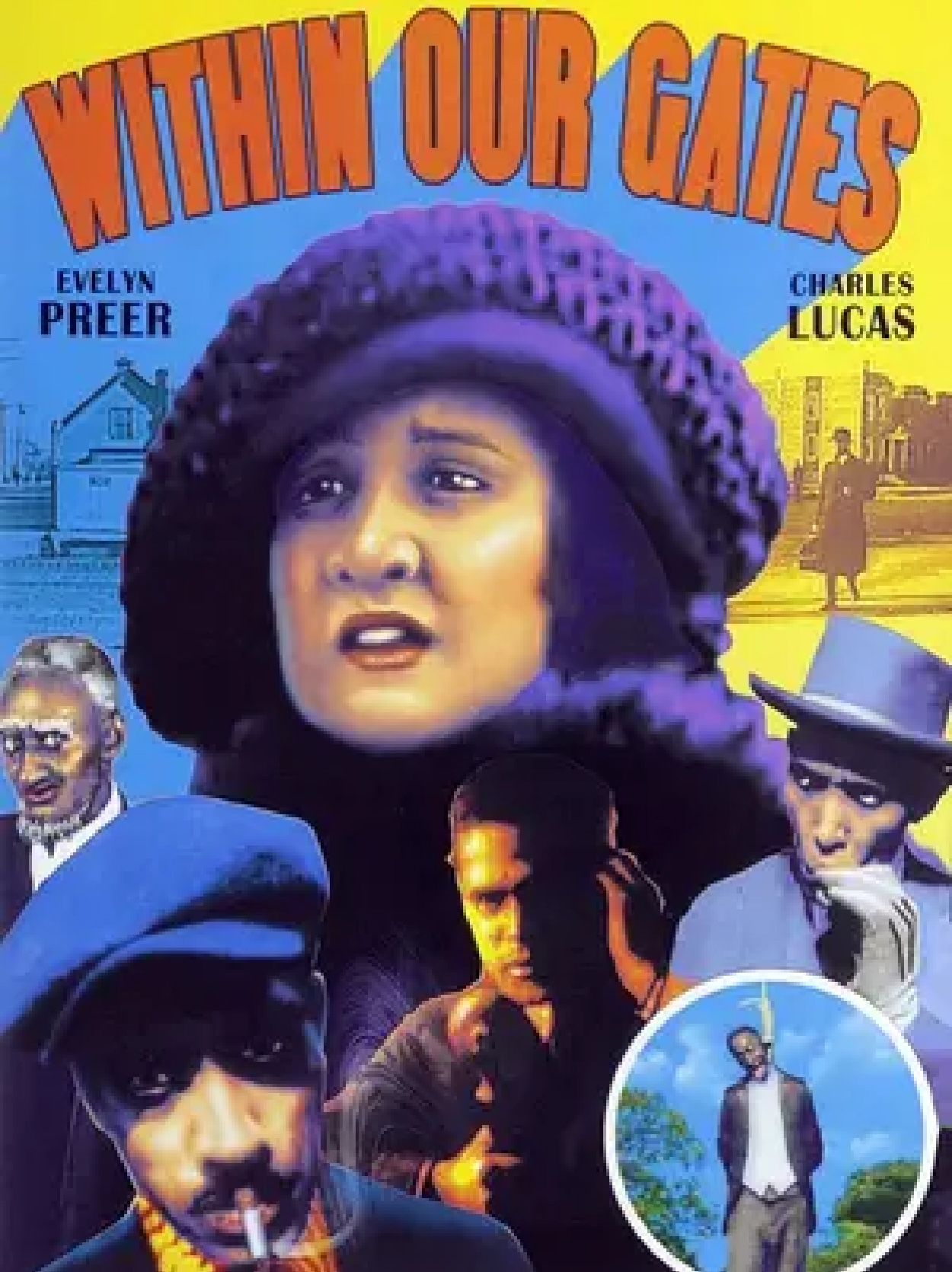

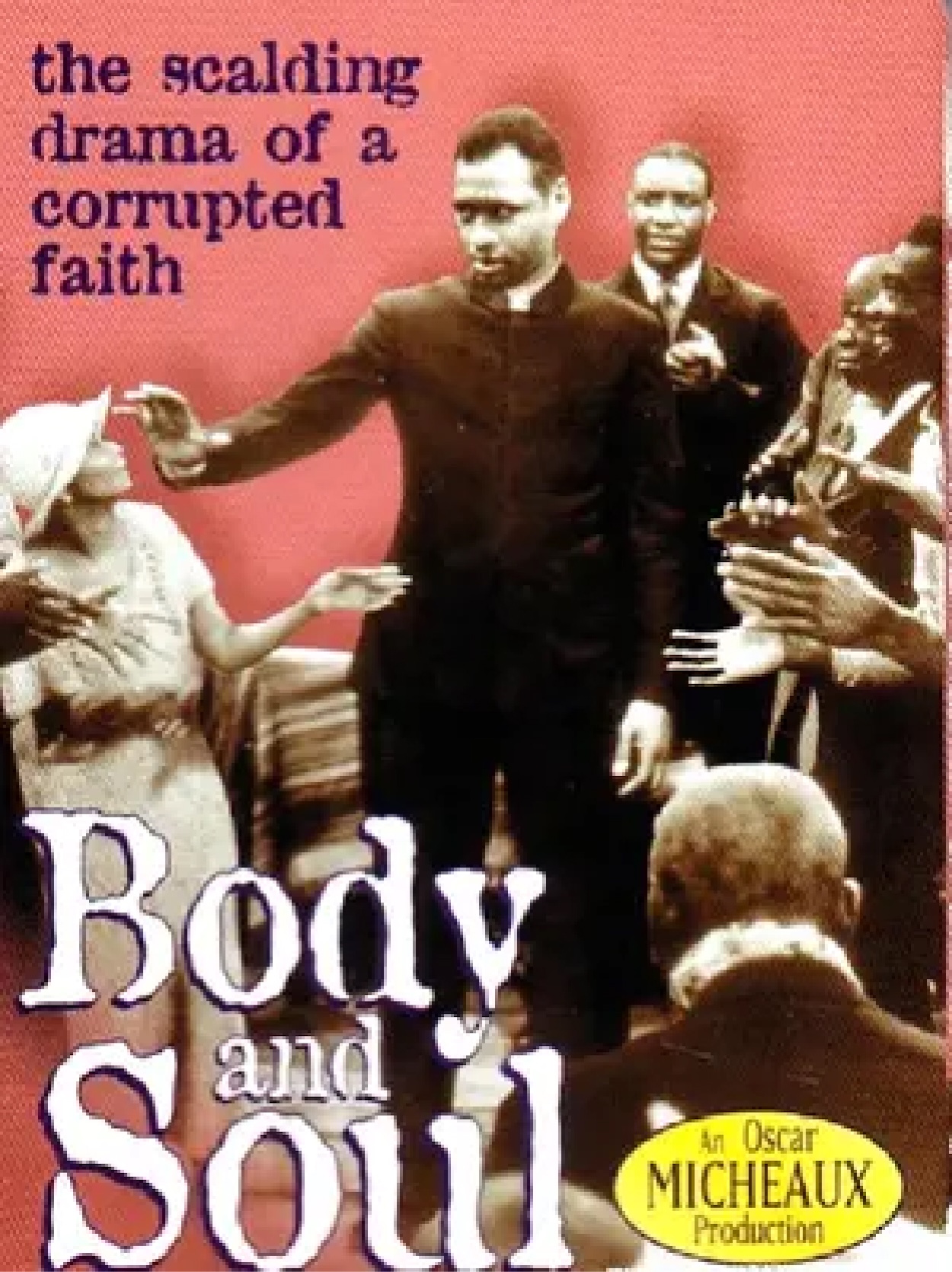

By the time he died on a train in 1951, Micheaux had written, produced and directed more than 40 features between 1918 and 1948—most of them “race films” made for Black audiences and shown in segregated theaters across the country. Many are lost, victims of neglect, racism and the fragile nitrate stock on which he worked. But what survives—silent epics like Within Our Gates (1920) and talkies like Body and Soul (1925) and Swing! (1938)—amounts to something like an alternate history of American cinema: a Black modernity unfolding just beyond Hollywood’s line of sight.

This is the story of that parallel film world, and of the people who built their lives around it—audiences who saved money for Micheaux tickets, actors who gambled their reputations on his low-budget sets, entrepreneurs who booked his films in dusty storefront theaters and polished picture palaces alike. Together, they created a self-sustaining ecosystem of Black storytelling years before mainstream Hollywood could imagine such a thing.

From Illinois farm boy to race-film mogul

Oscar Devereaux Micheaux was born in 1884 in Metropolis, Illinois, one of 13 children of parents who had been enslaved in Kentucky before the Civil War. As a teenager he left home for Chicago, where he worked a series of service jobs before landing a coveted position as a Pullman porter—a job that placed Black men in close proximity to wealth but firmly in its service.

Those porter years mattered. On the rails, Micheaux met Black businessmen, professionals and soldiers traveling between Northern cities; he also witnessed the rigid color line that confined them to segregated cars in the South. That contrast between aspiration and humiliation would haunt his films, where polished strivers and small-town hustlers often collide.

Restless, he moved west and became a homesteader in South Dakota. The experiment nearly ruined him—bad weather, bad luck and mounting debts—but it gave him the frontier vistas and racial politics that shaped his first novel, The Conquest: The Story of a Negro Pioneer (1913), later reworked as The Homesteader (1917).

When White producers expressed interest in adapting The Homesteader but refused to put a Black director in charge, Micheaux made a different choice: he turned them down and decided to film it himself. In 1918 he founded the Micheaux Film & Book Company, selling stock and pre-selling his films to Black theater owners and community investors, often traveling in person to pitch his vision.

It was an early form of independent crowdfunding, decades before the word existed.

Building a cinema for Black audiences

From his base in Chicago and later New York, Micheaux wrote, financed, cast, directed and distributed his films largely on his own. Most played in a network of more than 600 “race theaters” in Black neighborhoods, as well as churches, lodges and school auditoriums that doubled as makeshift cinemas.

Micheaux’s films were “for us, by us” in an era when Hollywood’s most famous depiction of Black life was The Birth of a Nation (1915), a white-supremacist fantasia that glorified the Ku Klux Klan and depicted Black men as rapacious brutes.

He answered that film not with a manifesto but with a body of work. In Within Our Gates, his earliest surviving feature, Micheaux inverted the logic of Birth. Instead of a Black predator and white victim, he staged an attempted rape of a Black woman, Sylvia, by a white landlord, intercutting the assault with the lynching of her Black adoptive parents. The sequence exposed what Black communities had long known: lynching was not a defense of white womanhood but a tool of terror against Black progress.

For the Black viewers who filled segregated theaters, those images were both devastating and electrifying. The Chicago Board of Censors initially banned Within Our Gates, warning that its depiction of racial violence was “dangerous” in a city still tense after the 1919 race riot. Micheaux pushed back, recutting the film, appealing, and eventually getting it onto screens—where it drew huge crowds.

A generation later, a Black Chicago defender writer remembered those screenings as “the first time we saw ourselves suffering and resisting on screen, instead of shuffling and singing.” That testimony, cited in later scholarship, speaks to the personal connection audiences felt to Micheaux’s work.

Stories of strivers, schemers and the cost of passing

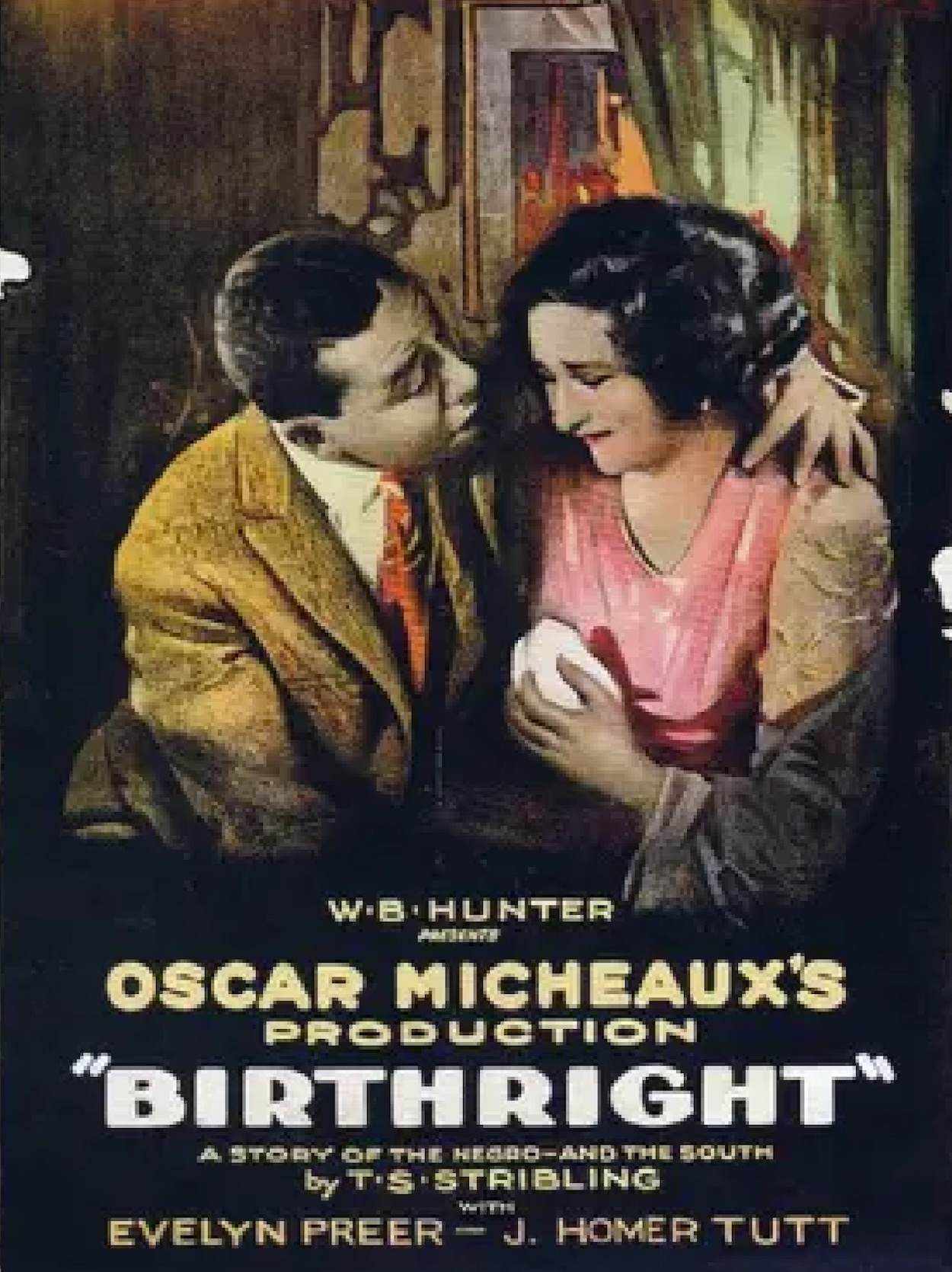

Micheaux’s filmography is sprawling—gangster thrillers, romantic melodramas, social-issue pictures—and many titles are lost or fragmentary. But a few surviving films reveal consistent obsessions: class tensions inside Black communities, religious hypocrisy, and the psychic costs of race.

In Body and Soul (1925), the most famous of his silents, Micheaux cast the young Paul Robeson in a dual role: an earnest inventor and his evil twin, a con man masquerading as a preacher. The false minister preys on a small Southern town, stealing church funds and assaulting a young woman who believes he will marry her.

Micheaux’s portrait of Black clergy—avaricious, cowardly, more concerned with collection plates than community uplift—infuriated some pastors and delighted others who recognized the critique. The film’s protagonist, an upright mother, rejects the preacher’s theatrics and demands education, not empty talk, for her daughter.

“We used to argue about that movie after church,” recalled an Atlanta deacon in an oral history recorded decades later for a Black film archive. “Some folks said Micheaux was airing dirty laundry. Others of us said: better we clean it ourselves than let white folks decide who we are.”

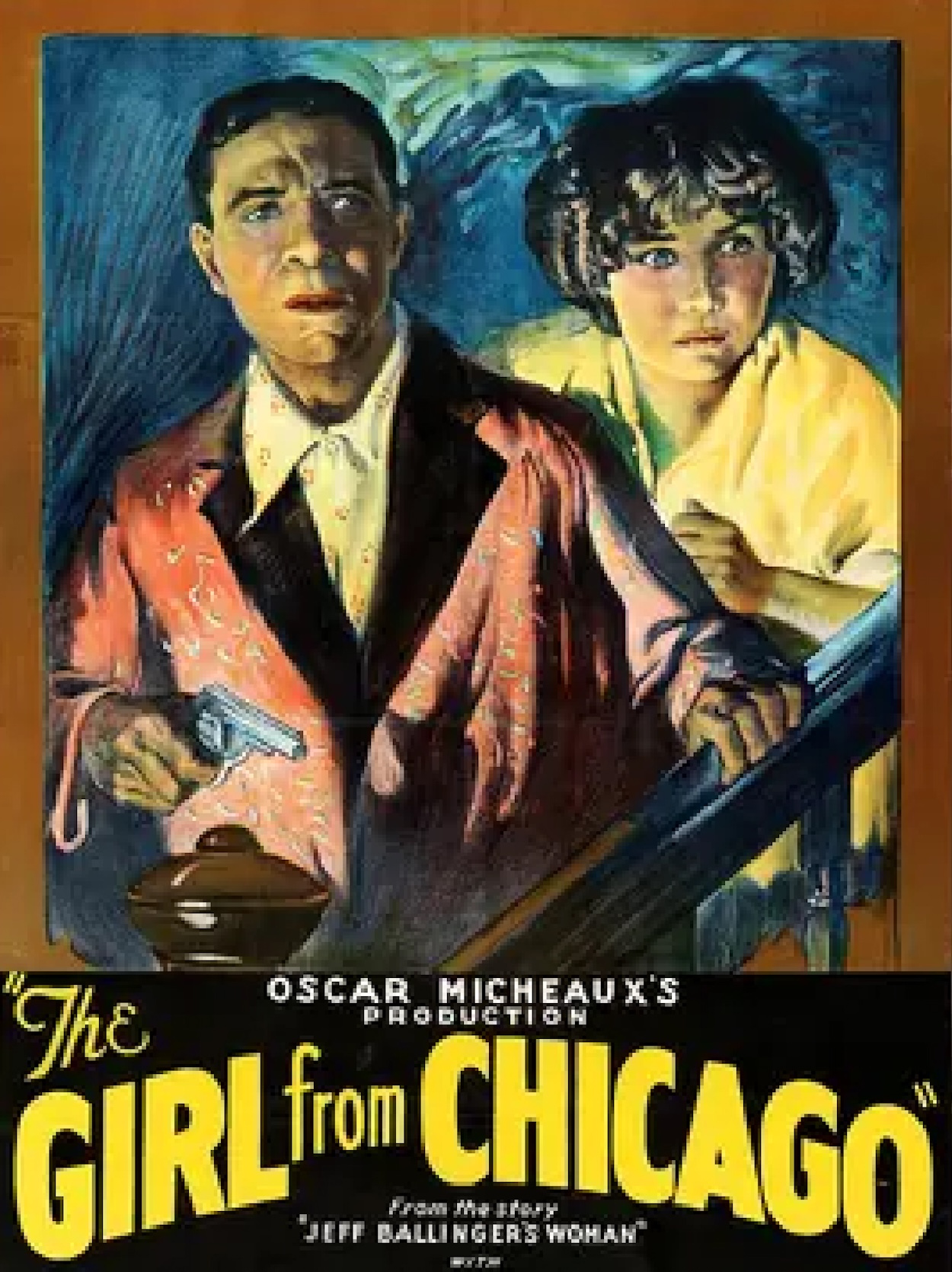

The tension between “respectability” and blunt truth runs throughout Micheaux’s work. His talkies, especially The Exile (1931), The Girl from Chicago (1932) and God’s Step Children (1938), took on colorism and the phenomenon of Black people “passing” for white.

In God’s Step Children, a light-skinned girl named Naomi repudiates her Black family, attempts to marry into white society and ultimately spirals into despair. The film is melodramatic, and by contemporary standards harsh in its judgments, but for Black audiences of the 1930s the figure of Naomi hit close to home. Passing was a real, if rarely discussed, survival strategy in the Jim Crow era.

A Kansas City teacher who saw the film as a teen later told a historian that she recognized a cousin in Naomi: “We knew she was passing in St. Louis. Nobody said it out loud. Micheaux’s movie said what we whispered.”

Even when Micheaux’s scripts leaned on coincidence and melodrama, his characters were ripped from life: Pullman porters, bootleggers, small-town businessmen, musicians working the Black club circuit. He set scenes in nightclubs and dance halls not just for spectacle but to document performers—jazz bands, blues singers, tap dancers—who rarely appeared in mainstream cinema.

DIY empire: how Micheaux financed his dreams

If Micheaux’s movies were radical on screen, his business practices were just as bold. Working outside the Hollywood system meant he had no studio backing, no bank loans on generous terms, and no guarantees that a film would ever recoup its costs.

Instead, he cultivated an intricate network of small investors. He sold stock in his company, raised money from Black fraternal organizations, and struck deals with theater owners who would advance him funds in exchange for first access to new films. He also rehypothecated his own work—re-cutting and re-releasing films under new titles when he needed cash.

Actors and crew members often accepted deferred pay, trusting that Micheaux’s hustling would eventually bring in box-office revenue. Sometimes it did. Sometimes it didn’t.

Lucia Lynn Moses, who starred in Body and Soul, later told an interviewer she’d taken the role for “little more than carfare” but considered the work priceless. “There were so few chances for a colored woman to play anything but a maid,” she said. “Oscar wrote women who thought, fought, made choices. That was worth more than the money he didn’t have.”

Micheaux could be ruthless. His relentless scheduling—multiple features in a single year, often shot in weeks—left little room for perfectionism. Budgets were threadbare, continuity inconsistent; critics, including some Black journalists, sometimes dismissed his films as technically crude.

But others saw the roughness as a sign of urgency, not incompetence. Brooklyn-based writer and curator Ashley Clark has argued that Micheaux’s work “thrived outside Hollywood, turning constraints into a style that was jagged, confrontational, and distinctly modern.”

A parallel public sphere

To understand Micheaux’s impact, it helps to picture the full ecology around his films.

On a Saturday night in 1921, for instance, Black audiences in Chicago might have lined up outside the States Theater to see Within Our Gates after weeks of debate in the Black press over whether censors would allow its lynching scenes to be shown.

Church ladies who sold pies for the building fund were now selling tickets. Local NAACP organizers handed out literature on anti-lynching campaigns in the lobby. Young couples watched from balcony seats, then argued on the walk home about Sylvia’s romantic choices or the minister who urges his flock to accept injustice for heavenly rewards.

Newspapers like the Chicago Defender and the Pittsburgh Courier treated Micheaux releases as news events, reviewing plots, announcing casting calls, and sometimes criticizing the films’ depiction of class divisions or gender politics.

This feedback loop—movies sparking editorials, editorials influencing future scripts—turned Micheaux’s cinema into a kind of rolling town hall on Black life.

A similar process played out across the South and Midwest. In small towns where Jim Crow law barred Black people from white theaters, enterprising business owners turned barbershops, lodge halls and even converted barns into screening rooms for Micheaux prints. One Mississippi barber remembered tacking a white bedsheet to the back wall and charging nickels for kids, dimes for adults. “It wasn’t just a picture show,” he later said. “It was us seeing us.”

What Comes Next

For now, the restored house remains closed as its stewards plan the next phase: programming.

Behind the scenes, Daydream Therapy, the Action Fund, and local partners are sketching out a future that could include artist residencies, small performances, educational visits, and collaborations with Tryon schools and churches. The house is too small to handle heavy tourist traffic; the challenge is to build a sustainable model of “ethical cultural tourism” that benefits the Black community around it rather than displacing it.

There are unresolved tensions. Simone’s complicated feelings about her hometown still hover over Tryon, as do questions about how a global icon’s birthplace can be both a local landmark and an international destination. Some residents worry about rising property values and the possibility that the very neighborhood that nurtured Simone could be priced out of its own history.

At the same time, there is a sense that what happens in this little house may help reshape American preservation more broadly. Black homes and neighborhoods, especially modest ones, have often been deemed unworthy of saving; their buildings are too small, too altered, too ordinary for the traditional canon of “heritage.” In centering a three-room pier-and-beam house in Tryon, Leggs argues, preservationists and artists alike are insisting that the roots of Black genius are themselves worthy of monumental care.

Clash with Hollywood and the limits of visibility

For decades Micheaux worked in a cinematic universe that barely intersected with Hollywood’s. His budgets rarely topped a few tens of thousands of dollars; MGM musicals could cost 100 times that. High-profile distributors largely ignored his pictures; white critics seldom reviewed them.

Yet Hollywood could not entirely look away. Some scholars note that Micheaux’s early success, along with that of other Black producers, helped persuade white studios to experiment with casting Black actors in more substantial roles, if only to compete for Black audiences’ dollars.

The exchange was unequal. When the industry transitioned to sound in the late 1920s, the cost of equipment soared. Major studios could invest in sound stages and recording gear; Micheaux had to cobble together resources, sometimes recording dialogue in echoing storefront spaces. The result: many of his early talkies suffer from muddy audio and abrupt cuts.

Critics ridiculed these technical flaws, but audiences often shrugged them off. “We weren’t going to the picture show for the sound quality,” one Detroit auto worker recalled. “We were going to see colored folks in tuxedos, in big houses, in trouble that wasn’t just scrubbing floors.”

Still, the financial strain was real. By the 1940s the race-film market had begun to shrink, squeezed by World War II, rising costs and the slow trickle of Black performers into mainstream films. Micheaux’s output fell, and his last movies, including The Betrayal (1948), struggled to find the same audience fervor.

He died three years later, largely forgotten by the industry he helped to shape.

Rediscovery and the long shadow of a pioneer

The neglect didn’t last forever. Beginning in the 1960s, Black film scholars and archivists—among them Pearl Bowser, Charles Musser and Jane Gaines—began tracking down surviving Micheaux prints in private collections and foreign archives.

In 1979, a nearly complete print of Within Our Gates turned up in Spain, mislabeled La Negra. It was painstakingly restored by the Library of Congress, with English intertitles reconstructed from Micheaux’s novels and other films. That discovery helped establish Micheaux not just as a historical curiosity but as a major artist, worthy of preservation alongside D.W. Griffith and Sergei Eisenstein.

Retrospectives in New York and London in the 1990s and 2000s, along with the release of the five-disc Pioneers of African-American Cinema box set in 2016, brought his work to new audiences. Critics re-evaluated him as an auteur whose jagged narratives and bold politics anticipated later independent cinema.

The ripple effects are visible across Black film history. Spike Lee has cited Micheaux as a spiritual ancestor; so have Julie Dash and Ava DuVernay. When contemporary directors tackle colorism, religious hypocrisy or the psychic toll of striving in a racist society, they are, knowingly or not, working in the terrain Micheaux mapped a century ago.

Jacqueline Stewart argues that Micheaux’s real legacy lies not only in his images but in his insistence on owning them. He “made the majority of his films through his own production company,” she notes, and kept creative control even when money was scarce. For Black filmmakers navigating today’s streaming-dominated industry, that model of independence—however precarious—still resonates.

The people who kept Micheaux’s images alive

For all the newfound praise, Micheaux’s survival as an icon owes as much to everyday people as to critics or curators.

It was projectionists who quietly dubbed and repaired worn prints so they could play one more weekend in a small-town theater. It was schoolteachers who stored reels in classroom closets when a traveling exhibitor moved on. It was the patrons who saved ticket stubs and lobby cards as keepsakes, not knowing they were preserving pieces of film history that archives would later scour the world to find.

In oral histories, some now-elderly viewers still describe their first Micheaux movie with startling clarity: the outfits, the packed aisles, the nervous laughter when a character challenged a white authority figure. One woman, who saw The Girl from Chicago as a teenager in the 1930s, put it simply: “You don’t forget the first time a movie takes your life serious.”

Their memories underline a central truth about Micheaux’s cinema: it was never only about one man’s genius. It was about a collective hunger—for representation, for debate, for a chance to see Black life projected at heroic scale, in three reels and a cloud of cigarette smoke.

A century later, what do his films ask of us?

Watching Micheaux now can be jarring. His camera placements can be static, his edits abrupt; his politics can veer between radical and conservative, especially around gender and sexuality. Some scenes court respectability, others relish scandal.

But if we watch him only as a curiosity from cinema’s past, we miss the challenge his work still poses.

Micheaux asks: Who gets to define a community on screen? Whose contradictions are allowed to be visible? What stories are we willing to tell about ourselves, even when airing them might damage our image in the eyes of outsiders?

A century after Within Our Gates, Black directors are winning Oscars, running studios, launching global franchises. Yet questions about creative control, representation and audience remain urgent. Streaming platforms can green-light a project overnight—and pull it just as quickly. Diversity gains can prove fragile when markets tighten.

In that precarious landscape, Micheaux’s stubborn insistence on making, selling and owning his films feels less like a historical footnote than a blueprint. He worked with what he had, leaned on his community, and trusted that Black audiences would show up for stories that took them seriously.

He was, as one contemporary critic once groused, “a one-man studio with the ego to match.” But he was also something rarer: a filmmaker who treated his community not as background extras but as full protagonists—even when the production values were thin and the future of his company was one box-office weekend away from collapse.

If Hollywood still struggles to make good on its promises of inclusion, Oscar Micheaux’s films stand as both indictment and invitation. They remind us that long before a diversity initiative, there was a Black man with a borrowed camera, a stack of scripts, and an audience waiting in the dark—ready to see themselves, at last, in the flicker of light.