KOLUMN Magazine

The Plot That Ended in Death—and a Last-Minute Reprieve: Inside the Tremane Wood Case

Oklahoma Gov. Kevin Stitt on Thursday granted clemency to death-row prisoner Tremane Wood minutes before his scheduled execution, commuting his sentence to life without parole and capping a volatile, years-long case that has drawn scrutiny from judges, a divided clemency board and national media.

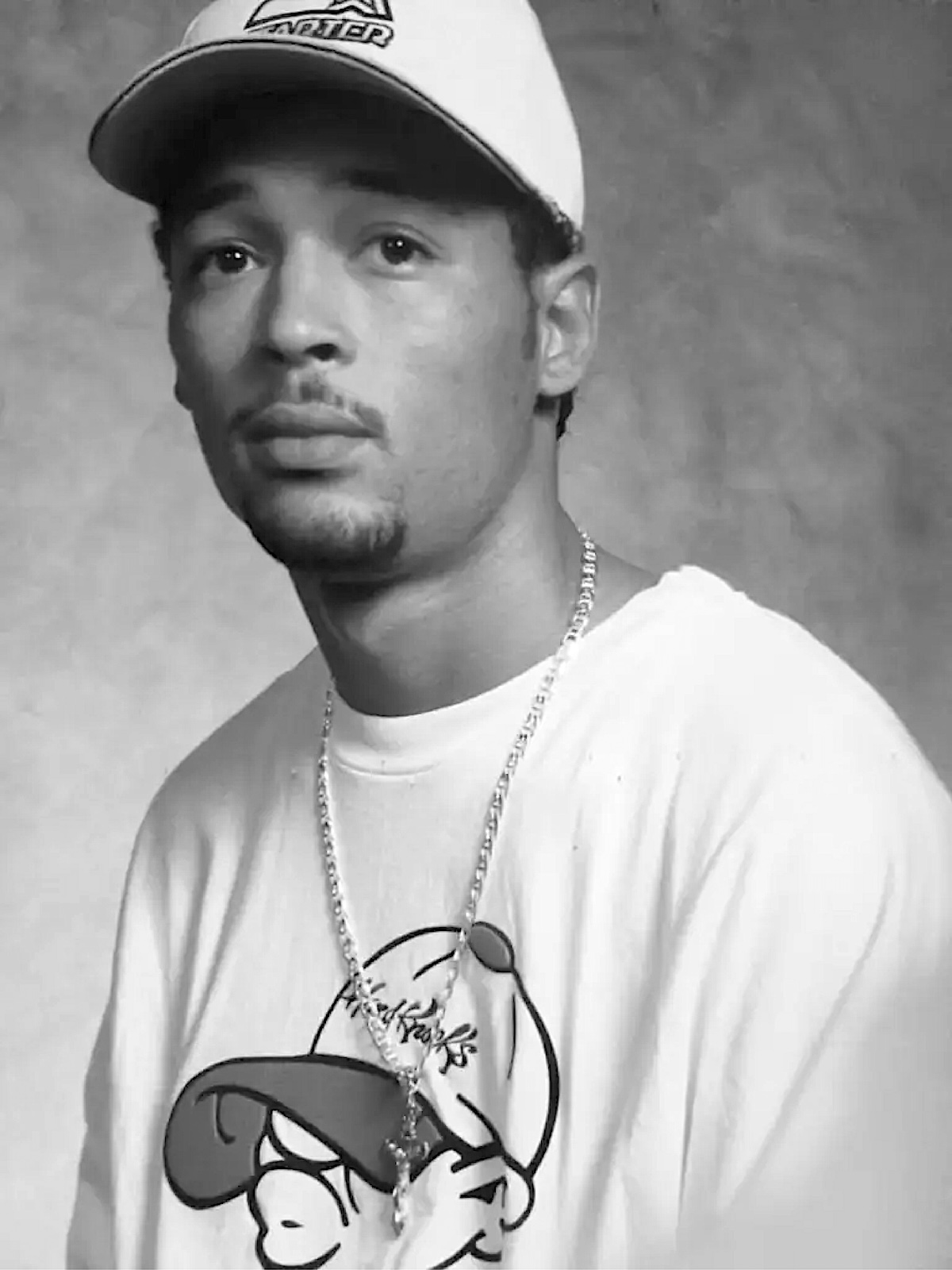

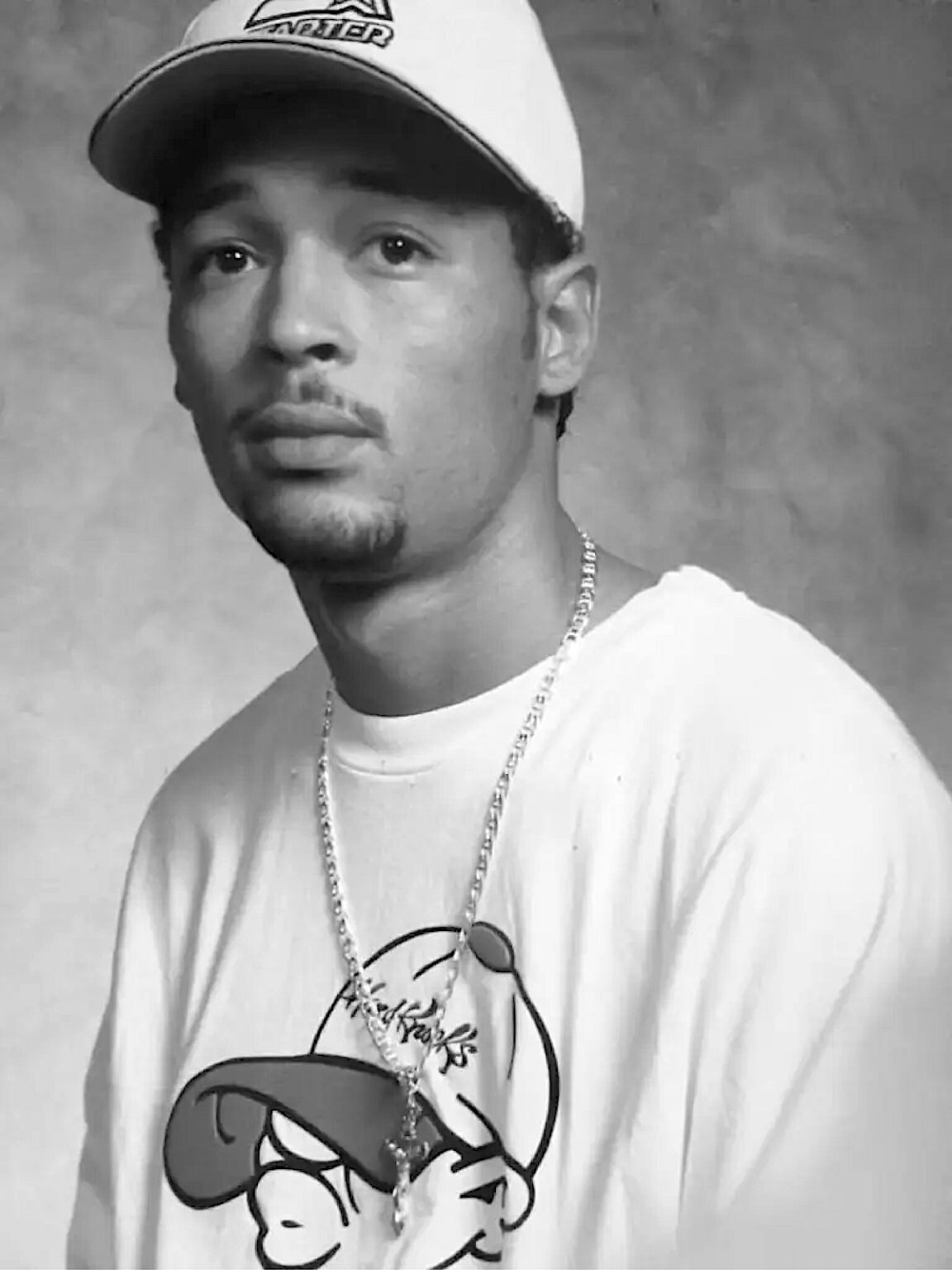

Tremane Wood was condemned for the 2002 killing of 19-year-old migrant farmworker Ronnie Wipf during a motel-room robbery in Oklahoma City. He has long admitted taking part in the robbery but maintained he did not wield the knife that pierced Wipf’s heart.

The governor’s decision followed a 3–2 recommendation for mercy by the Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board last week and a tense run-up in which the U.S. Supreme Court declined last-minute appeals. Stitt’s move marked only the second time in nearly seven years he has granted clemency to a person facing execution.

The Night of the Killing

The victim, Ronnie Wipf, a teenager from Montana traveling through Oklahoma for agricultural work, was lured into a robbery that prosecutors say turned deadly. According to court filings and trial transcripts summarized in Wood v. State (2021 OK CR 7), the plan had been set in motion days earlier by Wood, his brother Zjaiton “Jake” Wood, and two women, Sandra Washington and Taketa Thomas, both of whom later testified for the state.

According to the Court of Criminal Appeals of Oklahoma record:

The victim, Ronnie Wipf, a teenager from Montana traveling through Oklahoma for agricultural work, was lured into a robbery that prosecutors say turned deadly. According to court filings and trial transcripts summarized in Wood v. State (2021 OK CR 7), the plan had been set in motion days earlier by Wood, his brother Zjaiton “Jake” Wood, and two women, Sandra Washington and Taketa Thomas, both of whom later testified for the state.

According to the Court of Criminal Appeals of Oklahoma record:

On New Years Eve 2001, Ronnie Wipf and Arnold Kleinsasser went to the Bricktown Brewery in Oklahoma City where Zjaiton, Tremane, Lanita and Brandy were celebrating. Near closing time, Wipf and Kleinsasser met Lanita and Brandy believing they were two ordinary girls celebrating the new year together. Lanita and Brandy agreed to accompany Wipf and Kleinsasser to a motel on the pretext of continuing to celebrate the new year. Brandy, Lanita, Tremane, and Zjaiton then made a plan whereby the women would pretend to be prostitutes and the brothers Wood would arrive at the motel later and rob Wipf and Kleinsasser.

Once in their room at a Ramada Inn, Lanita made a telephone call to Zjaiton to let him know where they were, ending her conversation by saying, “Mom, I love you” so the victims would not be suspicious. The call to “Mom” was followed by some general conversation among the four which included a discussion of what each did for a living. Lanita told Kleinsasser that “this” is what she did and he realized that she meant she earned her living by having sex with men. That revelation was followed by a negotiation whereby the two women agreed to have sex with Wipf and Kleinsasser for $210.00.Since neither man had that much money, Brandy drove Kleinsasser to a nearby ATM. He gave her the money he withdrew and they returned to the room.

Back at the motel, the women went into the bathroom together, and shortly after, someone pounded on the door and called out, “Brandy, are you in there? Brandy, are you ready to go home? “Wipf refused to open the door and urgently told Kleinsasser to call the police. Before he could reach the phone, Lanita picked it up and pretended to call the police. Since it was now clear that the women were not going to have sex with them, Wipf demanded the return of their money. After a brief period of pandemonium in the room, Wipf opened the door and the women ran out. Recognizing a white car as the one Zjaiton and Tremane were driving, they got in and waited. Meanwhile, two masked men rushed into the motel room, a larger man, subsequently identified as Zjaiton Wood, holding a gun and a smaller man, subsequently identified as Tremane Wood, brandishing a knife. Zjaiton pointed the gun at Kleinsasser’s head and demanded money. Kleinsasser gave him the rest of the money in his wallet. Zjaiton then joined Tremane in his attack on Wipf. As the three struggled, Kleinsasser heard one of the intruders say, “Just shoot the bastard” and then a gunshot. Tremane then turned his attention to Kleinsasser, demanding more money. Kleinsasser showed him his empty wallet, and Tremane hit him on the head with the knife. Tremane rejoined the struggle with Wipf and the fight moved into the bedroom area. Kleinsasser could see Wipf was bleeding and knew that he was seriously injured. While the two intruders struggled with Wipf, Kleinsasser escaped and sought help from the motel office. Before anyone could unlock the office door and help him, however, Kleinsasser fled to a nearby apartment complex to hide. From his vantage point there, he watched the motel and saw a white car leave the parking lot. He saw people come and go throughout the night, but, with no sense of whom they were, remained in hiding. It was 6:00 a.m. before he returned to the scene of the attack and learned of Wipf’s death from a police detective.

A jury convicted Tremane Wood of first-degree murder in 2004, and a judge imposed a death sentence the following year. In a related proceeding, Jake Wood later testified that he had stabbed Wipf, though other trial testimony placed Tremane at the scene. Jake received life without parole and died in prison in 2019.

Competing Narratives: Who Held the Knife?

Wood’s account has been consistent for years: he acknowledged his role in the robbery but denied killing Wipf, saying Jake—who, according to defense lawyers, confessed to multiple people—inflicted the fatal wound. A defense filing also alleged that a key witness’s deal with prosecutors had not been fully disclosed at trial, an argument federal courts and, more recently, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to credit.

Prosecutors, led by Oklahoma Attorney General Gentner Drummond’s office, argued that evidence identified Tremane as the stabber and that his behavior in prison showed he remained dangerous—grounds, they said, to oppose clemency. Drummond publicly criticized the board’s 3–2 recommendation to spare Wood’s life.

Independent summaries by death-penalty researchers and local investigative outlets have emphasized the case’s unusual posture: one brother’s life-without-parole sentence after an admission of responsibility, and the other brother’s death sentence for the same killing. That asymmetry became a focal point during the clemency process.

The Lawyer Who Wasn’t Fully There: Attorney John Albert’s Alcohol Abuse

One of the most significant — and troubling — developments in Wood’s post-conviction appeals concerned his trial lawyer, John Albert.

Capital cases typically require months of sustained investigation. Defense attorneys gather social-history records, interview dozens of witnesses, consult experts in psychology and trauma, and craft a mitigation strategy that explains the defendant’s life story within the broader context of the offense.

Albert’s billing records told a very different story.

According to documentation included in Wood’s petition for U.S. Supreme Court review, Albert billed two hours total for the preparation and defense of Wood’s capital case. Not two hours on a particular hearing or motion — two hours overall.

When questioned years later during a court-ordered evidentiary hearing, Albert acknowledged his preparation was limited. He stated that he “did not prepare enough of a mitigation case” and had failed to hire an investigator. He attributed some of these shortcomings to the fact that he was carrying approximately 100 open cases during the same period.

Wood’s appellate attorneys brought forward these facts to argue that Albert’s representation violated the Sixth Amendment right to effective counsel. They cited Strickland v. Washington, the governing standard, which requires defendants to show two things:

1. That counsel’s performance was deficient, and

2. That the deficiency prejudiced the outcome.

The Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals agreed that Albert’s preparation had been minimal and that he carried an excessive caseload. But the court concluded that the core mitigation themes — including Wood’s traumatic childhood — had been presented to the jury in some form. It found that additional records would have been “cumulative,” and therefore ruled that Wood had not demonstrated prejudice under the Strickland standard.

A Case That Became a Referendum on Mercy

On Nov. 5, the Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board narrowly recommended that the governor commute Wood’s sentence to life without parole, citing concerns raised by defense counsel and Wood’s own statement accepting responsibility for the robbery while denying the killing. The Washington Post noted that Stitt had granted clemency only once before—commuting Julius Jones’s death sentence in 2021—while rejecting clemency in several other cases.

In the final 24 hours, national and local coverage intensified. The Guardian highlighted Wood’s longstanding claim that Jake was the killer and framed Stitt’s decision as the determining step after courts refused to intervene. (The Guardian) The Associated Press reported Thursday morning that, absent gubernatorial action, the execution would proceed at 10 a.m.; by late morning, Stitt granted clemency, halting the lethal injection.

Broadcast and local outlets detailed the underlying facts: the travel plans that brought Wipf to Oklahoma, the alleged lure into a motel room by two women, and the masked ambush that turned into a fatal stabbing—a snapshot of a robbery that prosecutors said escalated into murder.

Legal Cross-Currents and the “Felony Murder” Backdrop

The case unfolded within Oklahoma’s long and litigious death-penalty system. Wood’s direct appeals and post-conviction challenges failed, including a 2019 petition the U.S. Supreme Court declined to review. The AP reported that a more recent high-court appeal argued undisclosed benefits to a witness; that, too, was rejected before the clemency vote.

Advocacy organizations have pointed to the broader issue of felony-murder liability—under which participants in certain felonies can be held equally responsible when a killing occurs—even where the evidence suggests an accomplice was the actual killer. While that doctrine was not the only basis for Wood’s death sentence, analysts say it shaped the trial posture and the debate that followed.

Those tensions fed into the board’s deliberations and the governor’s calculus: whether the combination of lingering factual disputes, penalty disparities between brothers, and questions about the trial record supported commuting the sentence to life without parole.

The Families at the Center

For Wipf’s relatives, the legal wrangling has stretched over two decades. The AP and other outlets have noted that Stitt’s office consulted with the victim’s family in the days before the decision, part of a standard practice in Oklahoma capital cases. Their loss—a teenager killed during a road trip for work—has been the case’s somber constant.

Wood, now 46, addressed the board by video, saying, “I’m not a monster. I’m not a killer,” expressing remorse for his role in the robbery while denying that he stabbed Wipf. With the commutation, he will spend the rest of his life in prison.

What Stitt’s Decision Means

Stitt’s clemency order ends the prospect of execution but not the debate over culpability that has dogged the case. It also underscores the rare but consequential role Oklahoma governors can play after years of appeals. As the Post observed, Stitt has seldom exercised the clemency power; Thursday’s decision is an outlier that reflects both the split recommendation from his own board and the case’s evidentiary complexities.

For death-penalty policy watchers, the Wood case will likely be remembered for its mix of contested facts, mirrored by two brothers’ divergent punishments, and for the way a final executive act reordered an outcome that had seemed inevitable on execution morning. For the families—of both the victim and the condemned—it closes one chapter, even as the memory of a 19-year-old’s life cut short remains unresolved by any legal result.

Sources

Associated Press: timeline of appeals; governor’s last-minute clemency; case history of the Wipf killing. (AP News)

The Washington Post: divided clemency board; Stitt’s clemency record. (The Washington Post)

The Guardian: pre-decision overview emphasizing Jake Wood’s admissions and the case’s final turn to the governor. (The Guardian)

KOCO-TV (Oklahoma City): factual outline of the motel-room plot and travel background for the victims. (KOCO)

Death Penalty Information Center; The Oklahoman (archives): case posture, trial history, and sentencing context. (Death Penalty Information Center)

Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals: Wood v. State, No. PC-2019-431 (2021 OK CR 7), opinion summary via vLex.