When he died in 1979, Charles White had been influential, both in and outside of the art world. Now, a coming show at MoMA resurrects the American master.

AT THE TIME of his death in 1979, Charles White was the most famous black artist in the country. As the painter Benny Andrews said in Whiteʼs obituary in The New York Times, “People who didnʼt know his name knew and recognized his work.” He was a public figure who ranked in the imagination of black Americans alongside such figures as Harry Belafonte — a friend, collector and portrait subject — and Sidney Poitier, who eulogized the artist at his memorial service.

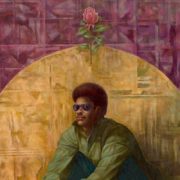

To begin a discussion about White like this, with the ending so to speak, is strange but appropriate. He was not a morbid or melancholy artist — quite the opposite, in fact: His images are passionately alive. But there is a sense, in his work, that time itself is not linear and history is not inevitable. His drawings and paintings include figures ranging from Harriet Tubman and Nat Turner to Langston Hughes and Sammy Davis Jr. (in character from the 1958 film “Anna Lucasta”) to anonymous street figures all the more captivating for their stoic mystery. In his 1943 mural, “The Contribution of the Negro to Democracy in America,” which remains to this day at the Clarke Hall auditorium at Hampton University in Virginia, White depicts a transhistorical scene that spans centuries, showing black Union soldiers marching alongside the folk singer Leadbelly, captured in the midst of performance, while George Washington Carver works away in his lab. “Black Pope” (1973), perhaps his most famous painting, casts a bearded black man with sunglasses, wearing a sandwich board and flashing a peace sign, as an ecclesiastical figure. His divinity is neither forced nor satirical, it just is, and though the painting, with its tremendous grandeur and respect for its subject, isn’t a self-portrait, it’s tempting to see it as one. But Whiteʼs project, in general, was bigger than himself, nothing less than the presentation of a history too long ignored: “Because the white man does not know the history of the Negro, he misunderstands him,” he said in 1940.

By M.H. Miller, The New York Times Style Magazine

Featured Image, Natalja Kent

Full article @ The New York Times Style Magazine