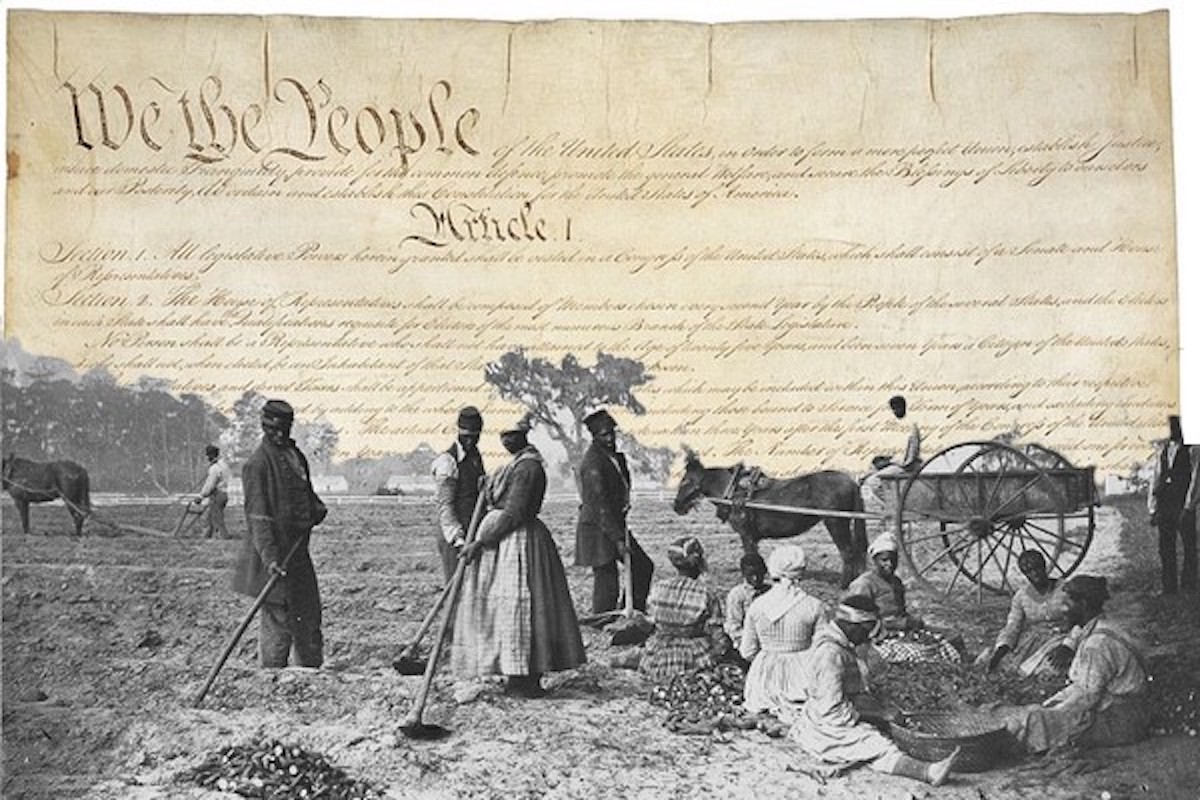

We are being told of the evils of “cancel culture,” a new scourge that enforces purity, banishes dissent and squelches sober and reasoned debate. But cancel culture is not new. A brief accounting of the illustrious and venerable ranks of blocked and dragged Americans encompasses Sarah Good, Elijah Lovejoy, Ida B. Wells, Dalton Trumbo, Paul Robeson and the Dixie Chicks. What was the Compromise of 1877, which ended Reconstruction, but the cancellation of the black South? What were the detention camps during World War II but the racist muting of Japanese-Americans and their basic rights? [mc4wp_form id=”6042″]

Thus any sober assessment of this history must conclude that the present objections to cancel culture are not so much concerned with the weapon, as the kind of people who now seek to wield it.

Until recently, cancellation flowed exclusively downward, from the powerful to the powerless. But now, in this era of fallen gatekeepers, where anyone with a Twitter handle or Facebook account can be a publisher, banishment has been ostensibly democratized. This development has occasioned much consternation. Scarcely a day goes by without America’s college students being reproached for rejecting poorly rendered sushi or spurning the defenders of statutory rape.

You must be logged in to post a comment.