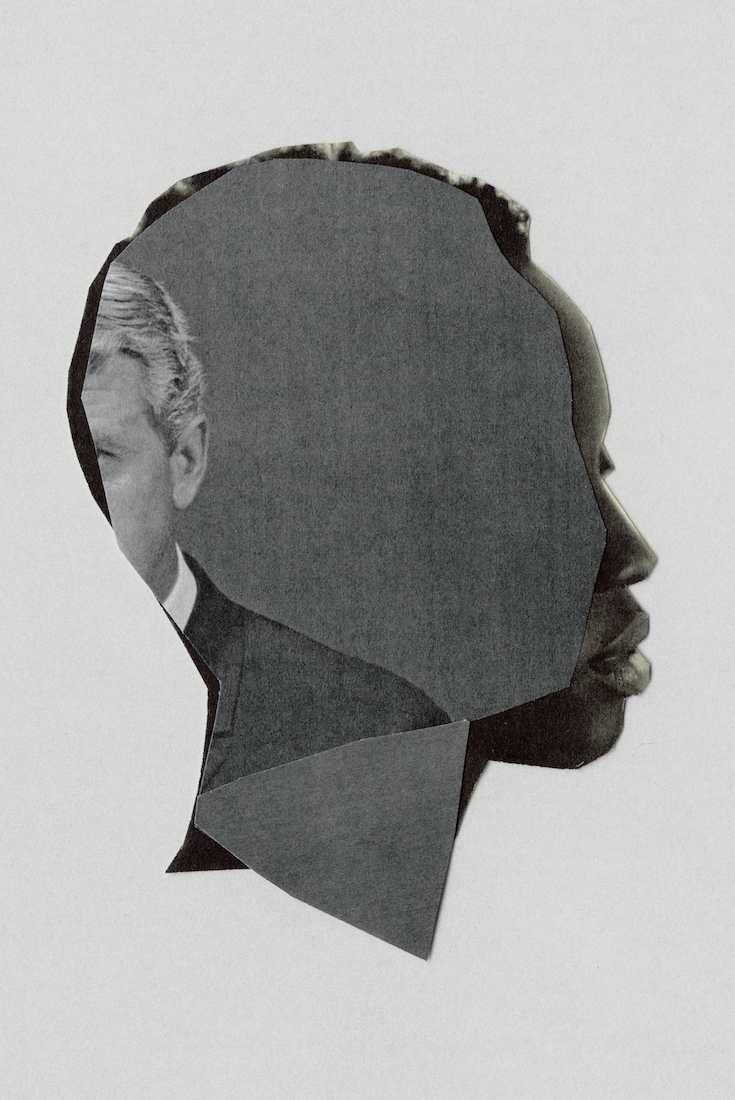

Photo illustration by Najeebah Al-Ghadban. Featured Image

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]n the early days of the run-up to the 2016 election, I was just beginning to prepare a class on whiteness to teach at Yale University, where I had been newly hired. Over the years, I had come to realize that I often did not share historical knowledge with the persons to whom I was speaking. “What’s redlining?” someone would ask. “George Washington freed his slaves?” someone else would inquire. But as I listened to Donald Trump’s inflammatory rhetoric during the campaign that spring, the class took on a new dimension. Would my students understand the long history that informed a comment like one Trump made when he announced his presidential candidacy? “When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best,” he said. “They’re sending people that have lots of problems, and they’re bringing those problems with us. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists.” When I heard those words, I wanted my students to track immigration laws in the United States. Would they connect the treatment of the undocumented with the treatment of Irish, Italian and Asian people over the centuries? [mc4wp_form id=”6042″]

In preparation, I needed to slowly unpack and understand how whiteness was created. How did the Naturalization Act of 1790, which restricted citizenship to “any alien, being a free white person,” develop over the years into our various immigration acts? What has it taken to cleave citizenship from “free white person”? What was the trajectory of the Ku Klux Klan after its formation at the end of the Civil War, and what was its relationship to the Black Codes, those laws subsequently passed in Southern states to restrict black people’s freedoms? Did the United States government bomb the black community in Tulsa, Okla., in 1921? How did Italians, Irish and Slavic peoples become white? Why do people believe abolitionists could not be racist?

I wanted my students to gain an awareness of a growing body of work by sociologists, theorists, historians and literary scholars in a field known as “whiteness studies,” the cornerstones of which include Toni Morrison’s “Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination,” David Roediger’s “The Wages of Whiteness,” Matthew Frye Jacobson’s “Whiteness of a Different Color: European Immigrants and the Alchemy of Race,” Richard Dyer’s “White” and more recently Nell Irvin Painter’s “The History of White People.” Roediger, a historian, had explained the development of the field, one that my class would engage with, saying, “The 1980s and early ’90s saw the publication of major works on white identity’s intricacies and costs by James Baldwin and Toni Morrison, alongside new works by white writers and activists asking similar questions historically. Given the seeming novelty of such white writing and the urgency of understanding white support for Ronald Reagan, ‘critical whiteness studies’ gained media attention and a small foothold in universities.” This area of study aimed to make visible a history of whiteness that through its association with “normalcy” and “universality” masked its omnipresent institutional power.

My class eventually became Constructions of Whiteness, and over the two years that I have taught it, many of my students (who have included just about every race, gender identity and sexual orientation) interviewed white people on campus or in their families about their understanding of American history and how it relates to whiteness. Some students simply wanted to know how others around them would define their own whiteness. Others were troubled by their own family members’ racism and wanted to understand how and why certain prejudices formed. Still others wanted to show the impact of white expectations on their lives.

You must be logged in to post a comment.