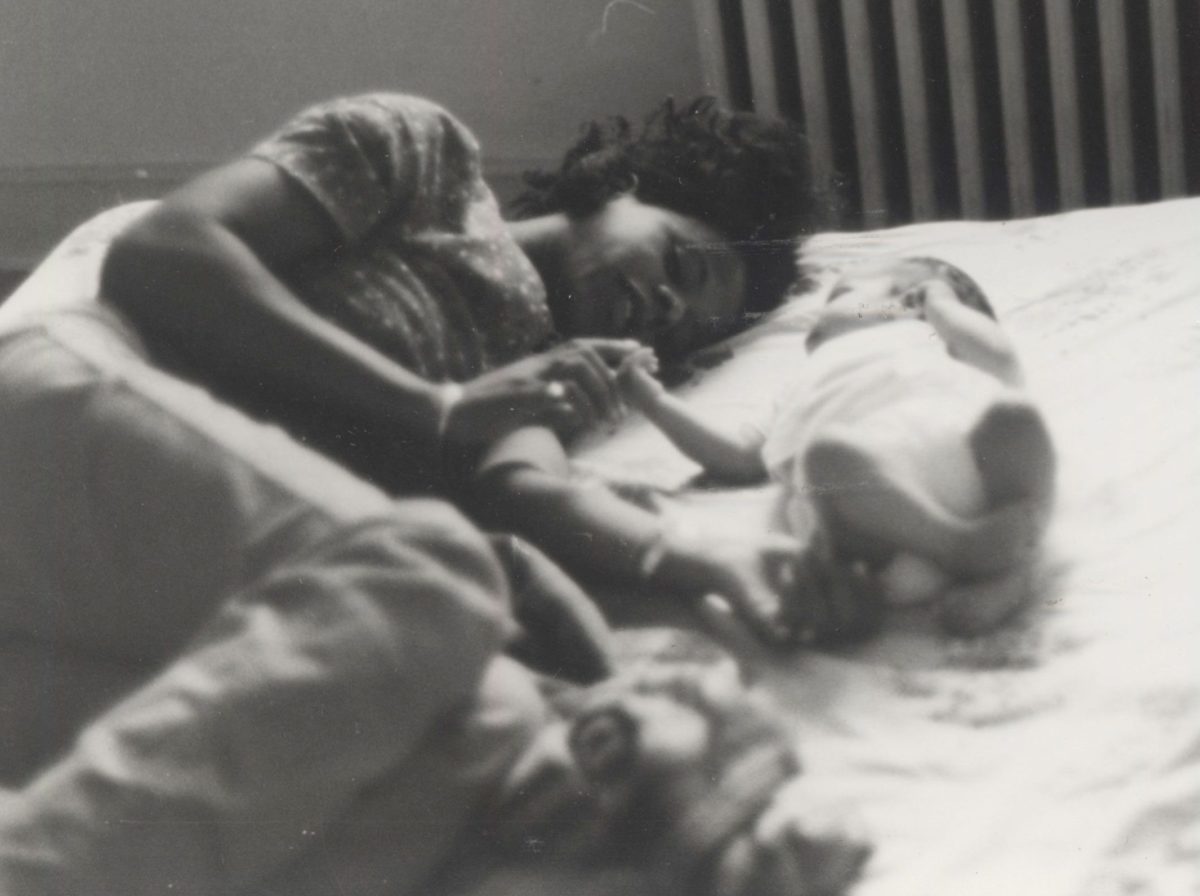

[dropcap]My[/dropcap] mother, Jean Walker, was the 13th of 15 children, born in 1949 to a church-going black family on a farm in Ohio. The house had only two bedrooms, so her parents slept on a pull-out bed on the porch in the summer and in the living room in winter. Her seven brothers slept in one bedroom, while the eight sisters shared the other. They attended a small school where the white kids sat up front and the black students at the back, separated by a row of empty desks. When she wasn’t studying, she did chores around the farm. The girls planted the vegetable gardens with corn and green beans, churned butter, did laundry, and took care of the younger children. The boys helped with the heavy work and looked after the animals. “With 14 siblings,” my mother used to say, “you’d better get to the table quick, or you weren’t going to eat that day.” There was never enough food or money to go around, but the family didn’t feel poor. Everyone around them was in the same situation. [mc4wp_form id=”6042″]

Jean was a sensitive girl who used to lie in the fields and watch the clouds scuttle by. Her parents were always quick with a whipping, and the casual violence wore on her soul. She found a cubbyhole in the back of a closet, where she’d hide out and devour books by the light of a bare bulb. Desperate to get away from her chaotic, rural home life, she worked tirelessly in high school to earn a scholarship to Antioch in Yellow Springs, Ohio, a liberal arts college and one of the first post-secondary schools to integrate. As a nascent feminist, she was drawn to Antioch’s progressive vibe. In 1971, she enrolled in women’s studies and journalism.

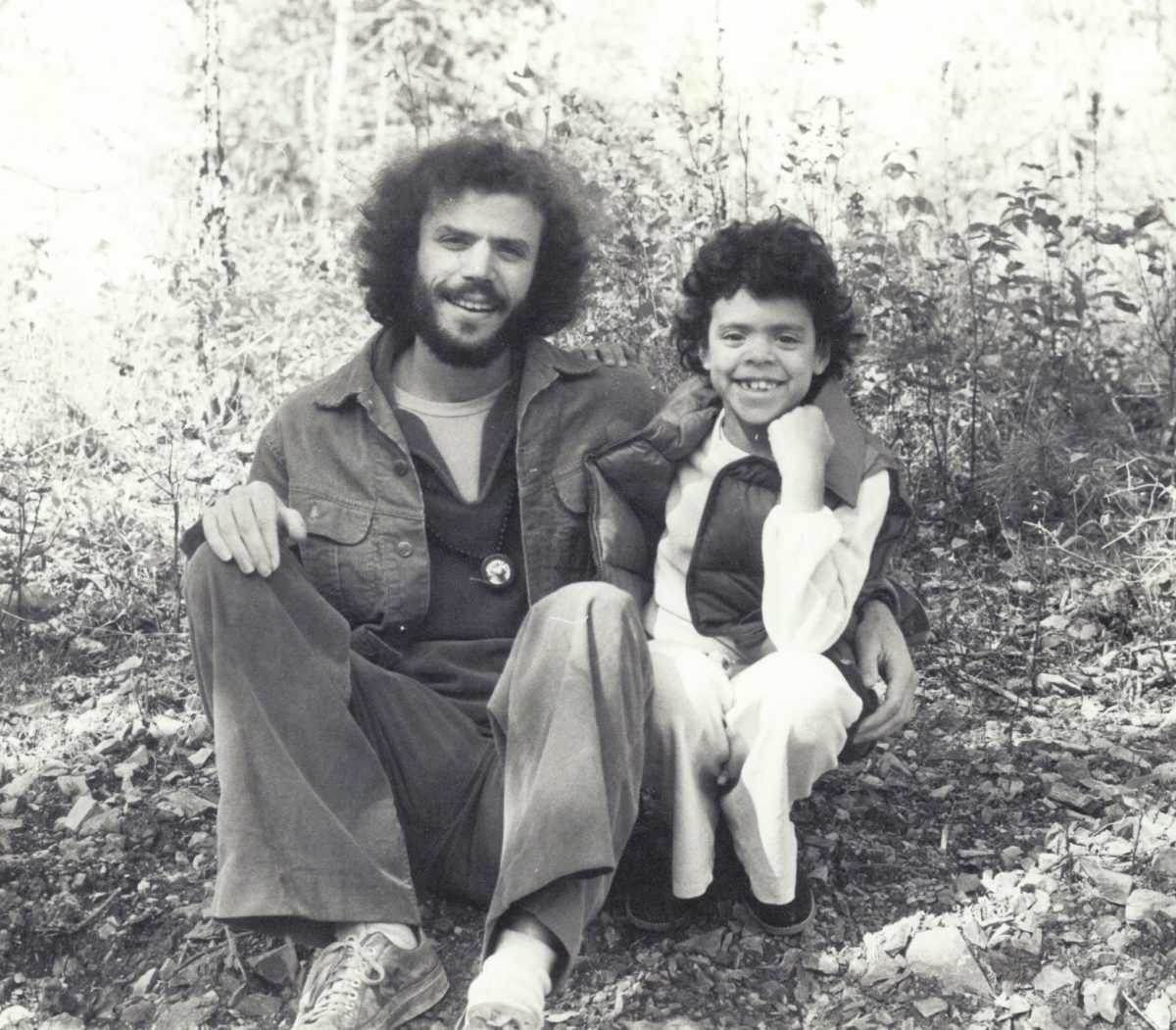

In her first semester, my mother attended feminist art lectures and Thelonius Monk concerts on campus. She had changed her name to DuShaun—she thought it sounded French—grown out her Afro and taken a liking to African-print dashikis that she found in the vintage shops. One evening, she went to see a student play. The only white boy in the production was a skinny Jewish kid in the role of a princely frog, leaping around the stage. She was drawn to his wild, free spirit and decided to introduce herself.

Anais is currently working on a TV series based on her experiences as a kid moving between multiple worlds., Photograph by Justin Aranha. Hair by Alex Topp. Makeup by Katharine Kates

Anais is currently working on a TV series based on her experiences as a kid moving between multiple worlds., Photograph by Justin Aranha. Hair by Alex Topp. Makeup by Katharine KatesHis name was Stanley Granofsky, and he was descended from Jews who’d fled the Russian pogroms at the beginning of the 20th century. His ancestors arrived on the shores of Halifax with everything they owned sewn into hidden pockets in their threadbare coats. They made their way to Toronto, and crowded near Kensington Market and the last remnants of the Ward, working in the haberdashery factories on Spadina. In 1945, my paternal great-grandfather and his son Phil started the paper company Atlantic Packaging, which they operated out of the family garage. A year later, Phil married my grandmother, Shirley Rockfeld.

You must be logged in to post a comment.