[dropcap]In[/dropcap] the original script for 1968’s Night of the Living Dead, the director George A. Romero refers to his flesh-eating antagonists as “ghouls.” Although the film is widely credited with launching zombies into the cultural zeitgeist, it wasn’t until its follow-up 10 years later, the consumerist nightmare Dawn of the Dead, that Romero would actually use the term. While making the first film, Romero understood zombies instead to be the undead Haitian slaves depicted in the 1932 Bela Lugosi horror film White Zombie.

By the time Dawn of the Dead was released in 1978 the cultural tide had shifted completely, and Romero had essentially reinvented the zombie for American audiences. The last 15 years have seen films and TV shows including Shaun of the Dead, 28 Days Later, World War Z, Zombieland, Life After Beth, iZombie, and even the upcoming Pride and Prejudice and Zombies.

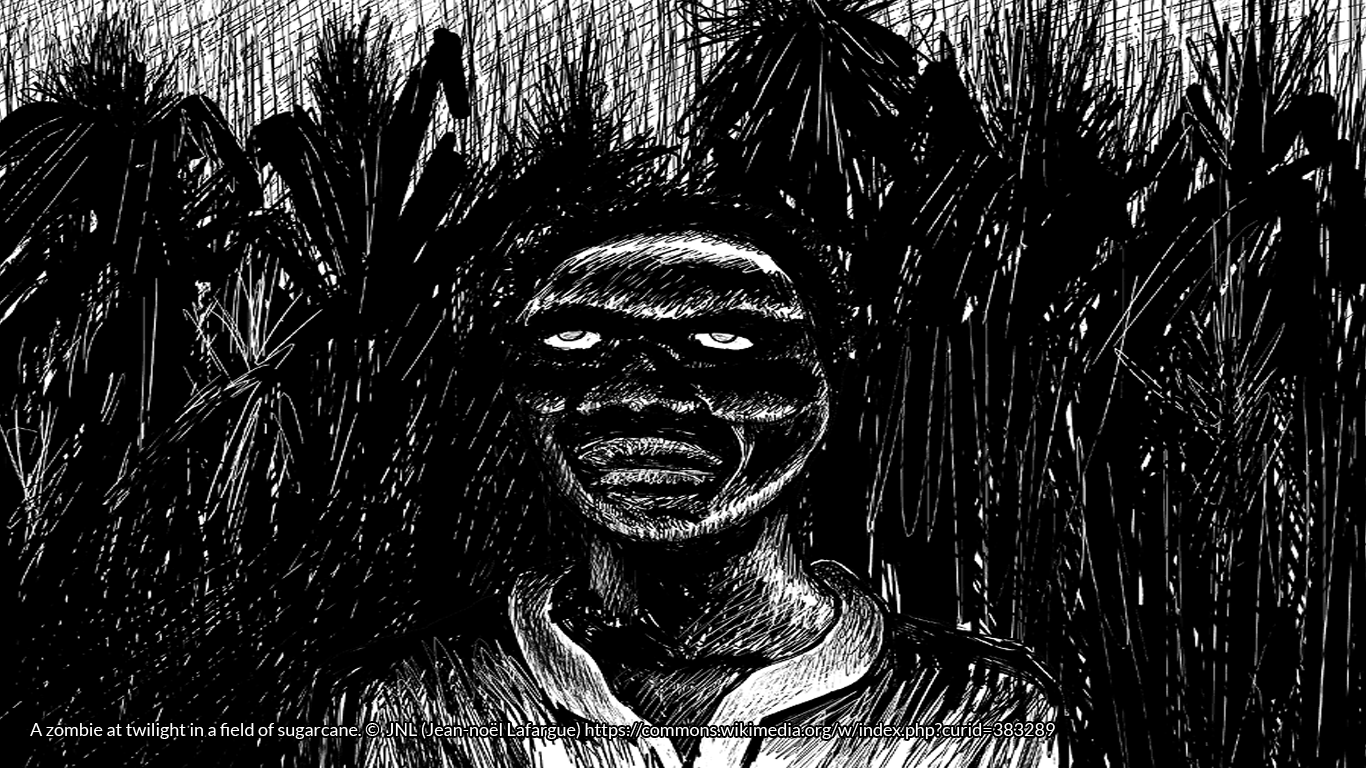

But the zombie myth is far older and more rooted in history than the blinkered arc of American pop culture suggests. It first appeared in Haiti in the 17th and 18th centuries, when the country was known as Saint-Domingue and ruled by France, which hauled in African slaves to work on sugar plantations. Slavery in Saint-Domingue under the French was extremely brutal: Half of the slaves brought in from Africa were worked to death within a few years, which only led to the capture and import of more. In the hundreds of years since, the zombie myth has been widely appropriated by American pop culture in a way that whitewashes its origins—and turns the undead into a platform for escapist fantasy. [mc4wp_form id=”6042″]

The original brains-eating fiend was a slave not to the flesh of others but to his own. The zombie archetype, as it appeared in Haiti and mirrored the inhumanity that existed there from 1625 to around 1800, was a projection of the African slaves’ relentless misery and subjugation. Haitian slaves believed that dying would release them back to lan guinée, literally Guinea, or Africa in general, a kind of afterlife where they could be free. Though suicide was common among slaves, those who took their own lives wouldn’t be allowed to return to lan guinée. Instead, they’d be condemned to skulk the Hispaniola plantations for eternity, an undead slave at once denied their own bodies and yet trapped inside them—a soulless zombie.

NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORY & CULTURE | WASHINGTON, DC

The National Museum of African American History and Culture is the only national museum devoted exclusively to the documentation of African American life, history, and culture. It was established by Act of Congress in 2003, following decades of efforts to promote and highlight the contributions of African Americans. To date, the Museum has collected more than 36,000 artifacts and nearly 100,000 individuals have become charter members. The Museum opened to the public on September 24, 2016, as the 19th and newest museum of the Smithsonian Institution. (Website).

You must be logged in to post a comment.