[dropcap]Walking[/dropcap] along the idyllic brick sidewalks of downtown Fredericksburg, Virginia, locals and tourists who pass the Olde Towne Butcher on the corner of William St and Charles St might notice a grayish-brown stone protruding from the sidewalk that is about the size and shape of an overturned bucket. A bronze marker at its base reveals that this stone was formerly used to auction off slaves.

Locals and city officials refer to it colloquially as “the slave block” or “the auction block”. Most peoples’ reaction upon learning of the block’s past is horror. Now, especially in the wake of the recent white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, the community is trying to decide what to do with it.

A common reaction is to throw this rock in the same mental heap of memorials and flags that honor the Confederate south and many are rushing to have it removed. Last week, an online petition was created to demand its removal. The petition currently has more than 2,500 signatures from across the country.

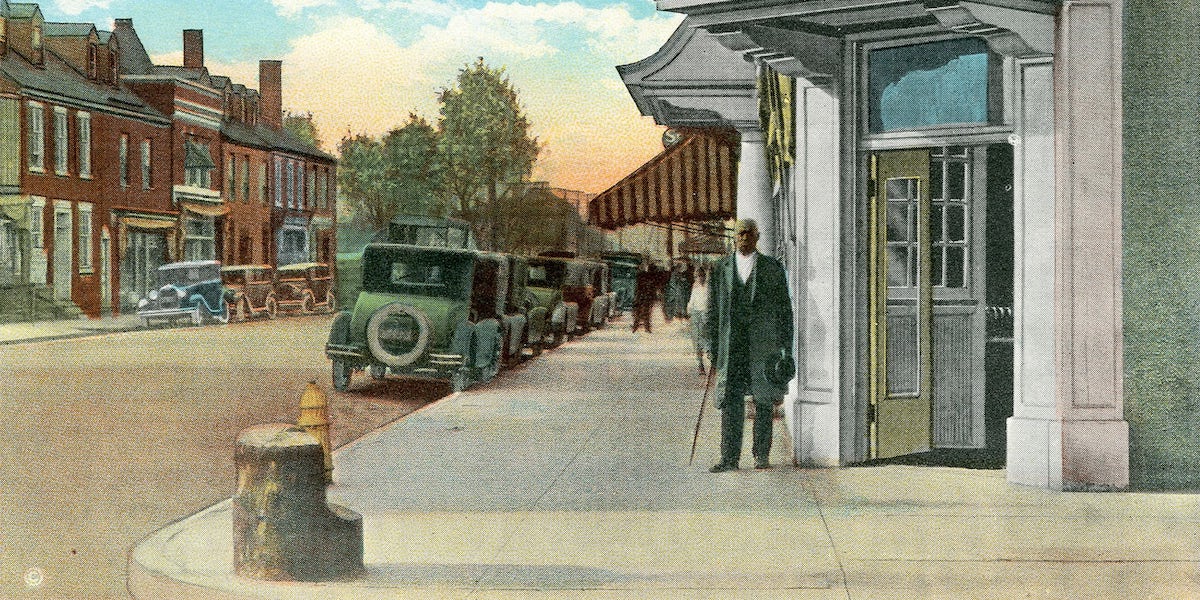

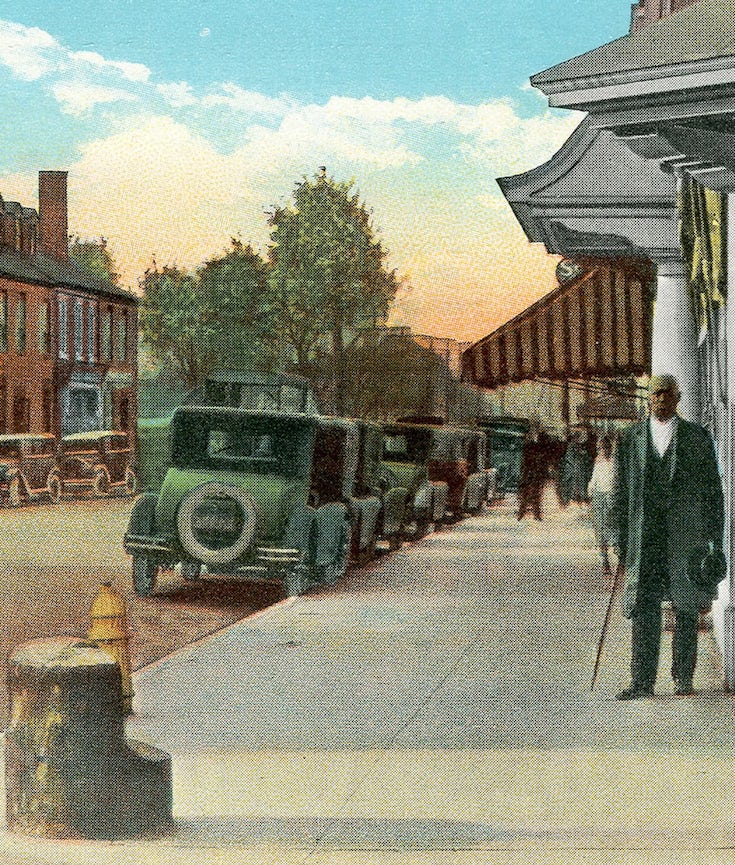

An illustration of the slave block, 1920s. | Albert Crutchfield

An illustration of the slave block, 1920s. | Albert Crutchfield

But for now, the block is not budging. Is Fredericksburg a town full of insensitive racists? Not quite. There are many deeply concerned residents in the town who feel that the slave block is categorically different from the monuments and statues that depict Confederate generals as heroes.

[mc4wp_form id=”6042″]

HISTORICALLY BLACK COLLEGES & UNIVERSITIES | HBCU

Historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) are institutions of higher education in the United States that were established before 1964 with the intention of primarily serving the African American community. They have always allowed admission to students of all races. Most were created in the aftermath of the American Civil War and are in the former slave states, although a few notable exceptions exist.

There are 107 HBCUs in the United States, including public and private institutions, community and four-year institutions, medical and law schools.

Most HBCUs were established after the American Civil War, often with the assistance of northern United States religious missionary organizations. However, Cheyney University of Pennsylvania (1837) and Lincoln University (Pennsylvania) (1854), were established for blacks before the American Civil War. In 1856 the AME Church of Ohio collaborated with the Methodist Episcopal Church, a predominantly white denomination, in sponsoring the third college Wilberforce University in Ohio. Established in 1865, Shaw University was the first HBCU in the South to be established after the American Civil War.

The Higher Education Act of 1965, as amended, defines a “part B institution” as: “…any historically black college or university that was established before 1964, whose principal mission was, and is, the education of black Americans, and that is accredited by a nationally recognized accrediting agency or association determined by the Secretary [of Education] to be a reliable authority as to the quality of training offered or is, according to such an agency or association, making reasonable progress toward accreditation.”Part B of the 1965 Act provides for direct federal aid to Part B institutions.

In 1862, the Federal government’s Morrill Act provided for land grant colleges in each state. Some educational institutions in the North or West were open to blacks before the Civil War. But 17 states, mostly in the South, had segregated systems and generally excluded black students from their land grant colleges. In response, Congress passed the second Morrill Act of 1890, also known as the Agricultural College Act of 1890, requiring states to establish a separate land grant college for blacks if blacks were being excluded from the existing land grant college. Many of the HBCUs were founded by states to satisfy the Second Morrill Act. These land grant schools continue to receive annual federal funding for their research, extension and outreach activities. The Higher Education Act of 1965 established a program for direct federal grants to HBCUs, including federal matching of private endowment contributions. (Wikipedia).

You must be logged in to post a comment.