Slinky, unfurling forms run around and through many of Kerry James Marshall’s paintings. They frame individual pictures’ contents and rope together serial canvasses into a narrative of styles and scenes. In his 1993 De Style, a barber shop (“Percy’s House of Style”) is crowded with African-Americans sporting regal, extravagant hair: on one man’s head sits an afro mass shaped into topiary wings, a girl balances a tangled hive of piled braids, and, cropped so we can’t see his head, a waiting customer wears a chunky golden “STUD” knuckle plate. Behind the braid-hive, a houseplant mimics its twisty form, and the red cord of Percy’s electric clippers repeats the cord draining from a wall clock mantled, high in the picture, by a snaky water hose.

[mc4wp_form id=”6042″]

Kerry James Marshall | Katherine McMahon

Kerry James Marshall | Katherine McMahon

De Style (1993) | Kerry James Marshall

De Style (1993) | Kerry James Marshall

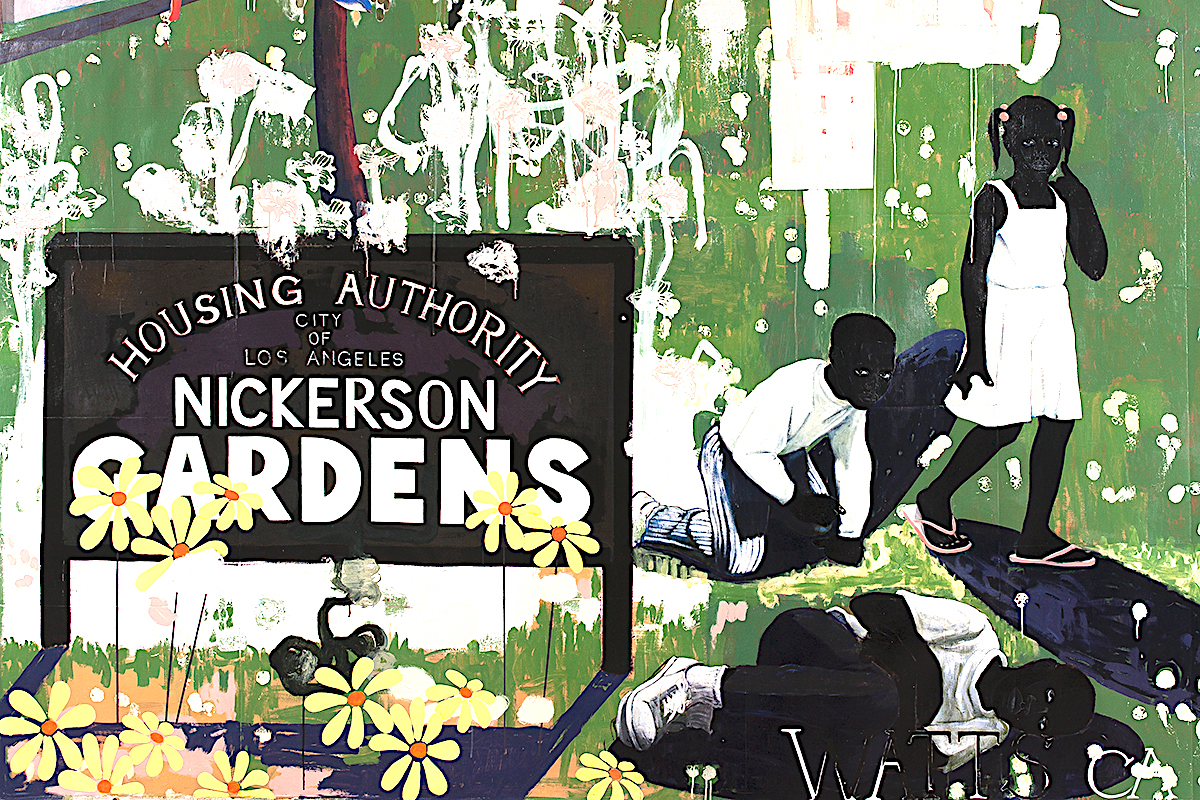

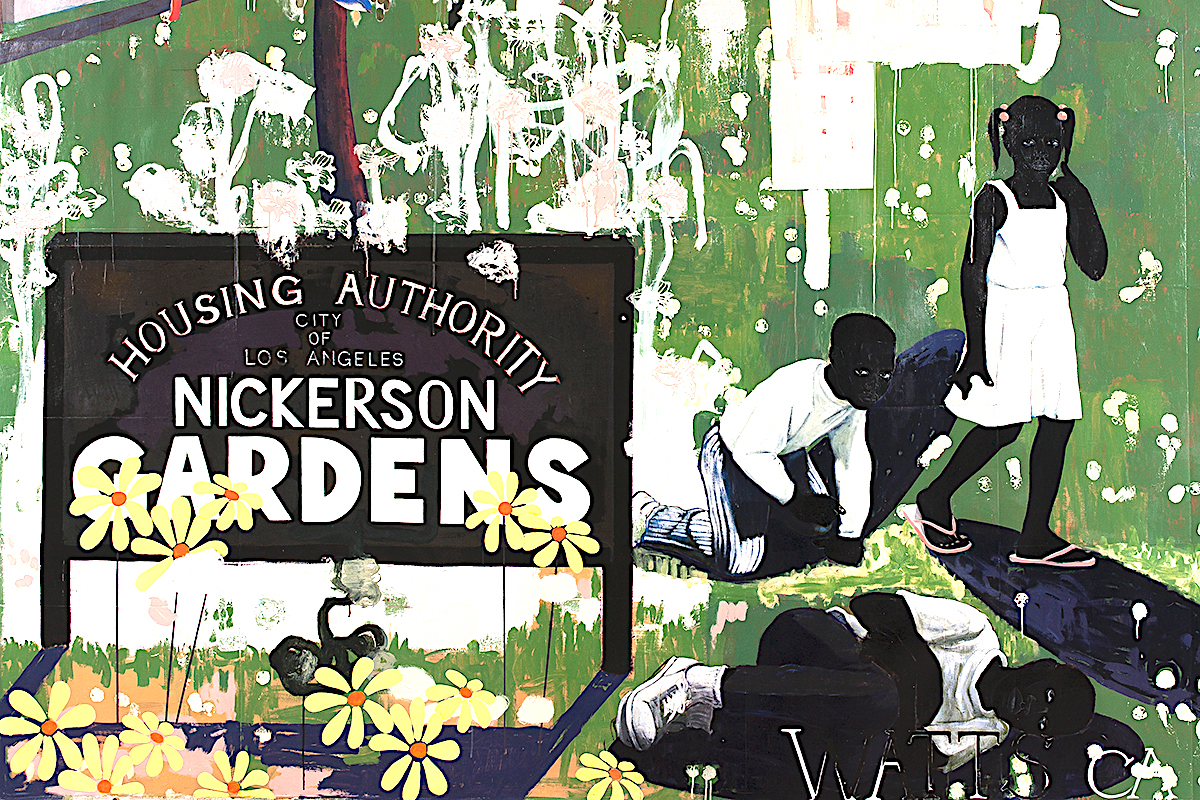

Watts (1963) | Kerry James Marshall

Watts (1963) | Kerry James Marshall

Jim Crow laws were state and local laws that enforced racial segregation in the Southern United States. Enacted by white Democratic-dominated state legislatures in the late 19th century after the Reconstruction period, these laws continued to be enforced until 1965. They mandated de jure racial segregation in all public facilities in the states of the former Confederate States of America, starting in 1896 with a “separate but equal” status for African Americans in railroad cars. Public education had essentially been segregated since its establishment in most of the South after the Civil War. This principle was extended to public facilities and transportation, including segregated cars on interstate trains and, later, buses. Facilities for African Americans were consistently inferior and underfunded compared to those which were then available to European Americans; sometimes they did not exist at all. This body of law institutionalized a number of economic, educational, and social disadvantages. De jure segregation existed mainly in the Southern states, while Northern segregation was generally de facto—patterns of housing segregation enforced by private covenants, bank lending practices, and job discrimination, including discriminatory labor union practices. “Jim Crow” was a pejorative expression meaning “Negro”.

Jim Crow laws—sometimes, as in Florida, part of state constitutions—mandated the segregation of public schools, public places, and public transportation, and the segregation of restrooms, restaurants, and drinking fountains for whites and blacks. The U.S. military was already segregated. President Woodrow Wilson initiated segregation of federal workplaces at the request of southern Cabinet members in 1913.

These Jim Crow laws revived principles of the 1800–1866 Black Codes, which had previously restricted the civil rights and civil liberties of African Americans. Segregation of public (state-sponsored) schools was declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court of the United States in 1954 in Brown v. Board of Education. In some states it took years to implement this decision. Generally, the remaining Jim Crow laws were overruled by the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, but years of action and court challenges have been needed to unravel the many means of institutional discrimination. (Wikipedia)

You must be logged in to post a comment.